For almost three decades, Véronique Geubel taught languages with a conviction that stories and sounds are the best gateways to learning. Yet she never imagined that her classroom experience would one day lead her to found her own publishing house.

The turning point came when the Paris-based publishing house ABC Melody, known for its musical and linguistic children’s books, suggested that she starts her own business to market some of their titles herself. That suggestion was the kickstart for Vivalangues, a small Belgian company based in Bastogne and dedicated to teaching languages. For Véronique, this was not just an entrepreneurial leap but a natural extension of her teaching career and lifelong interest in multilingual education.

Setting up a publishing house: from idea to legal IP framework

It was not so late for Véronique to learn that launching a publishing house requires not only patience but also a good understanding of intellectual property (IP) management.

With ABC Melody’s guidance, Véronique acquired an authors’ rights (copyright)* licence for two existing characters from a series originally published in English. This licence authorised her to translate and adapt these stories into Dutch and Luxembourgish, opening the door to markets that ABC Melody did not cover.

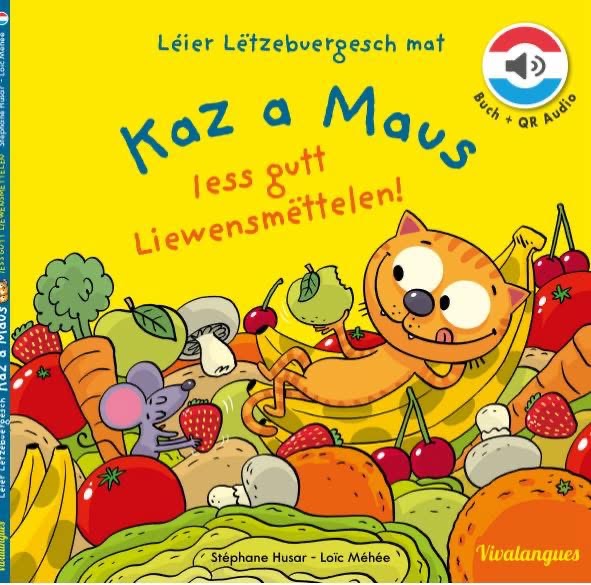

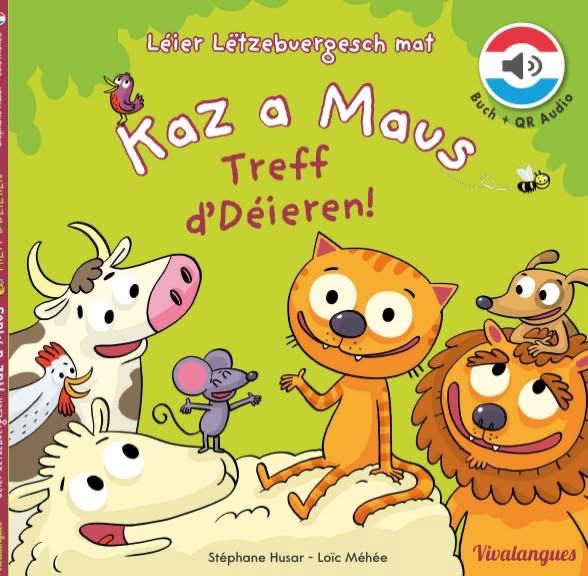

The project became her first series, Kaz e Maus, based on the popular Cat and Mouse books.

It was both a linguistic and entrepreneurial experiment: a teacher stepping into the roles of publisher, translator, and authors’ rights manager all at once.

Translating and adapting a concept by managing copyright

In Kaz e Maus, a cute mischievous cat introduces animals, fruits, and vegetables to its mouse friend, helping children learn words in Luxembourgish and Dutch. The adaptation maintained the original humour and rhythm but added a local touch to resonate with the new audiences.

The linguistic closeness between the two languages and the demand from teachers inspired the choice of markets. As a language teacher herself, Véronique recognised how vital cultural familiarity is to children’s learning. Translating Cat and Mouse into Kaz e Maus was therefore more than a translation; it was an act of localisation that preserved the story’s pedagogical value, while adapting it for different linguistic environments.

Setting up a publishing house means complying with a strict legal framework.

For the Luxembourgish edition, she took on the translation herself, gaining official credit as translator. For the Dutch version, she collaborated with a Dutch- language teacher who also receives royalties, which was a practical demonstration of how copyright contracts ensure fair recognition for all contributors.

“Setting up a publishing house means complying with a strict legal framework”, she says. “It was important for me to understand and respect the copyright chain.”

Her contract with ABC Melody defines her duties precisely: Vivalangues would handle copyright for the translated editions, pay royalties to the original creators, and manage new contributors, such as translators and voice actors. Therefore, Véronique learned to navigate the administrative side of copyright, which includes annual royalty statements and precise accounting.

In Belgium, each year, publishers must calculate total sales and pay royalties to authors, illustrators, and translators according to the terms of their contracts.

Beyond the prints, Kaz e Maus also became an audiobook, where the cat and mouse are brought to life by Luxembourgish voice artists. The recordings give young readers a playful, immersive way to experience the language, from listening to the pronunciation, tone, and rhythm of native speakers.

For this part, Véronique coordinated the contracts and payments herself. Each performer was paid for their day of recording and received copies of the book as a token of gratitude. Though small in scale, it required the same professionalism as any larger production: obtaining consent, clarifying usage rights, and managing neighbouring rights for performers.

“I am responsible for copyright and illustrations. This was stipulated in my contract with ABC Melody” she says. The experience taught her that even modest creative projects must handle IP carefully if they are to grow sustainably.

From small beginnings to an IP-respected creative ecosystem

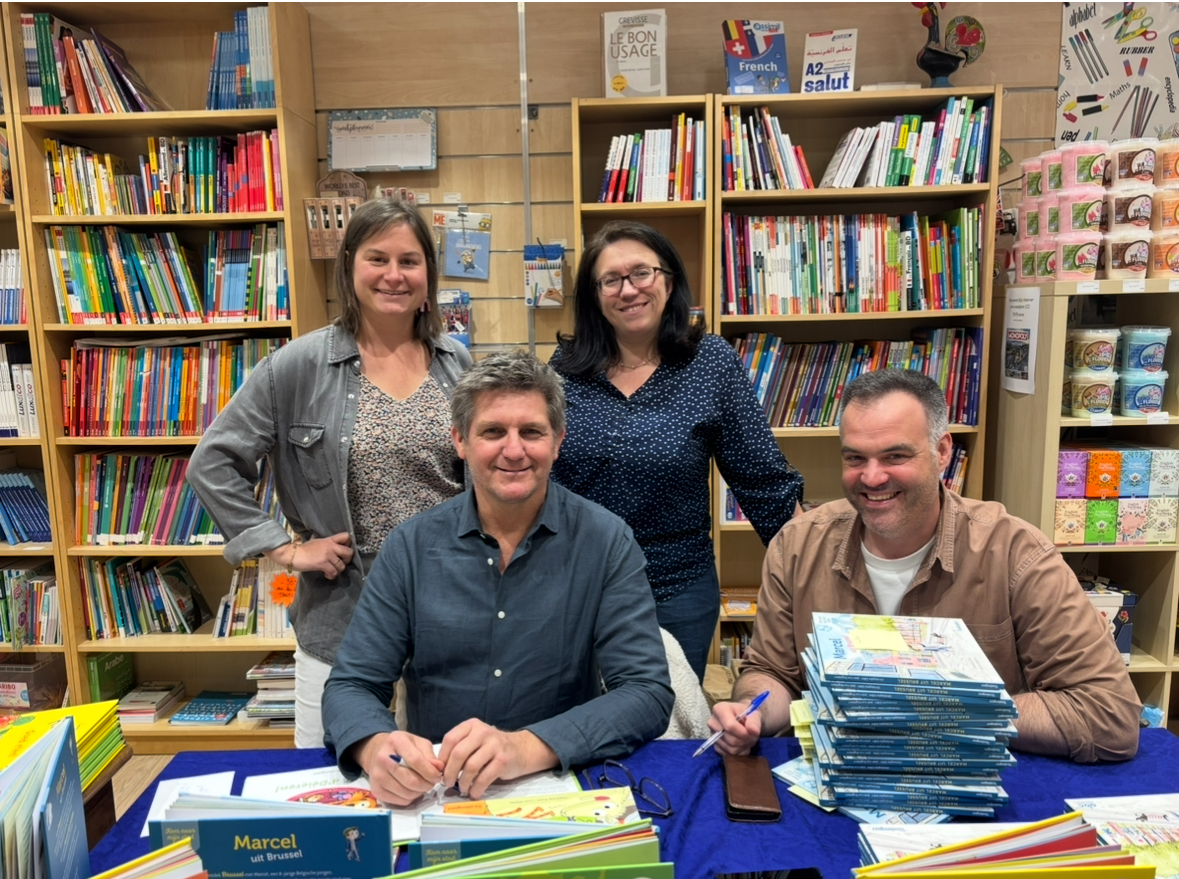

After months of translation, adaptation, and coordination, Kaz e Maus reached a milestone at the end of 2025: the books were picked up by one of Luxembourg’s largest booksellers. The partnership marked a new chapter for Vivalangues, giving the project national visibility.

“It will certainly help us with sales”, Véronique says, “which will enable us to pay the authors, illustrators, translators and voice artists who worked together on the project.”

Now, what began as a small translation initiative had become a full ecosystem of creative and commercial collaboration, sustained entirely by the clear structure of copyright and licensing agreements.

Copyright is not just a legal necessity; it is the bridge that allows small creative projects to reach big audiences.

For her, the adventure is far from over. The Kaz e Maus series will continue to grow, with new language versions and audio extensions planned. But the foundation will remain the same: transparency, respect for rights, and fair remuneration for all contributors.

Véronique’s journey demonstrates that small publishers, even with limited resources, can succeed by combining creativity, collaboration, and IP literacy. Through patience and perseverance, Vivalangues is now an example of how copyright fuels creativity.

She is clear in her last massage: “Copyright is not just a legal necessity; it is the bridge that allows small creative projects to reach big audiences. Just like in my little story!”.

* Copyright (or authors’ rights) confers upon its owners two main categories of exclusive rights:

(1) Economic rights, which include the rights to reproduce the work (including adaptations), to communicate it to the public (e.g., through performance, display, or broadcasting), and to distribute it (including by rental or lending).

(2) Moral rights, which relate mainly to paternity (the right of attribution) and integrity of the work. There are also rights related to copyright (often referred to as neighbouring rights) that protect the interests of three main groups of beneficiaries: performers, producers of phonograms (sound recordings), and broadcasting organisations in relation to their radio and television programmes.

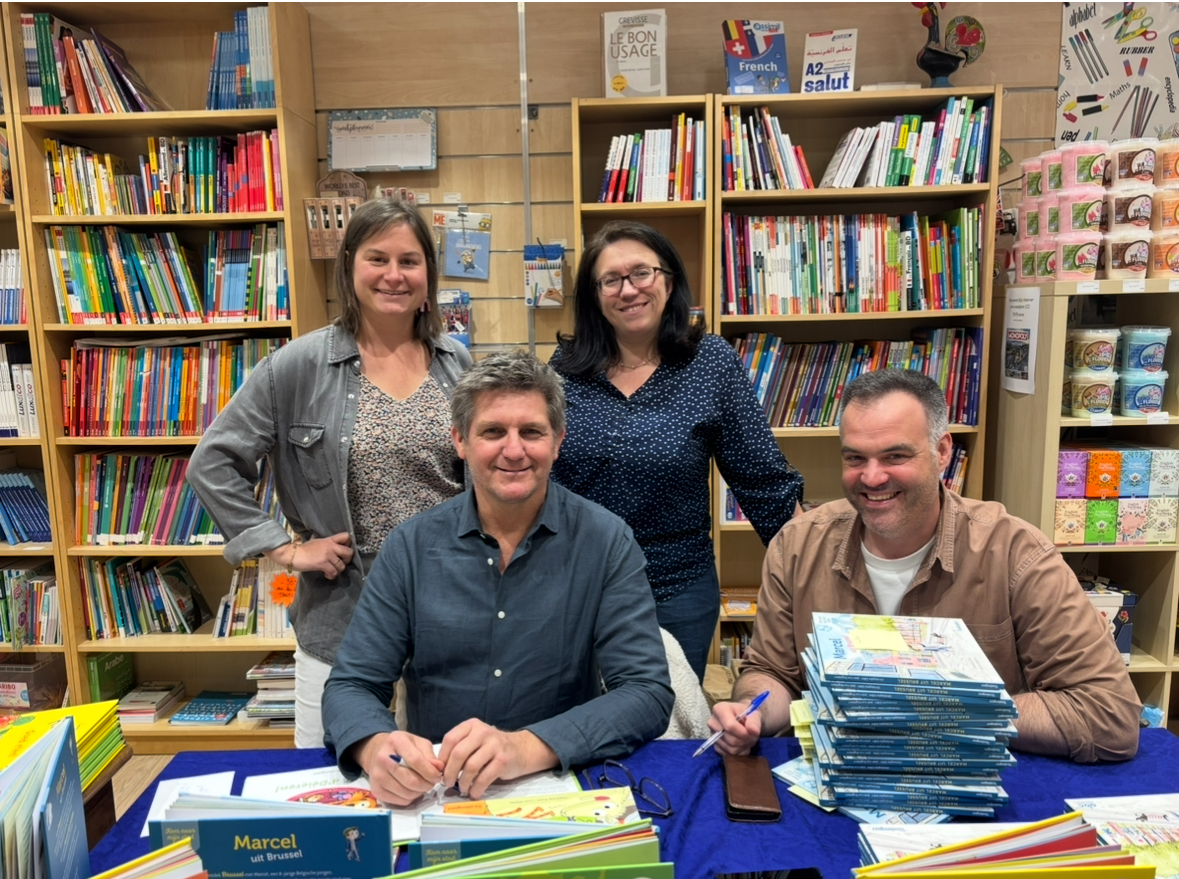

Images - Courtesy of Vivalangues

This Case Study was created under Creative FLIP, an EU co-funded project aimed at further increasing the long-term resilience of the CCSI in key areas such as Finance, Finance, Learning, Working Conditions, Innovation & Intellectual Property Rights.

Key Takeaways

• Copyright (authors’ right) and licensing contracts are the foundation of professional publishing.

• Fair remuneration for authors, illustrators, and translators helps to build long-term trust.

• Small publishers can reach national success through proper intellectual property (IP) management.

• Support from established publishers helps newcomers navigate IP complexity.