In the 1990s, Tudor Scripor, a young art student, would walk past a school for the blind almost every day on his way to class. This made him wonder: 'How do you learn about colours if you can't see them? Do colours remain just abstract words?' Little did he know that he would one day find the answers to these questions (and solve the problem!) by chance. This is his story

That coincidence happened almost two decades later, in 2012, when a blind student joined Scripor’s art class. He didn’t just want to memorise names of the colours; he wanted to recognise them independently. If letters, numbers, and even music can be read by touch, why not colour? All those unanswered questions became the compass of his life’s work.

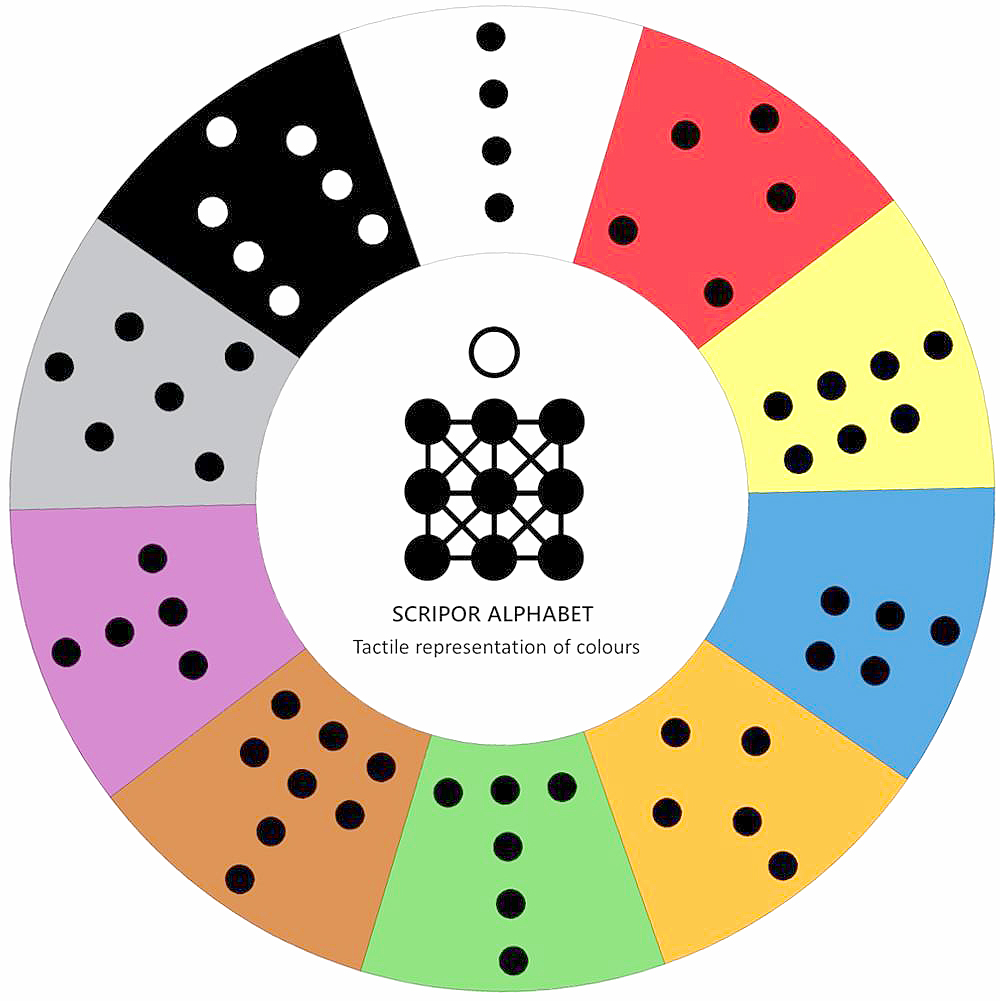

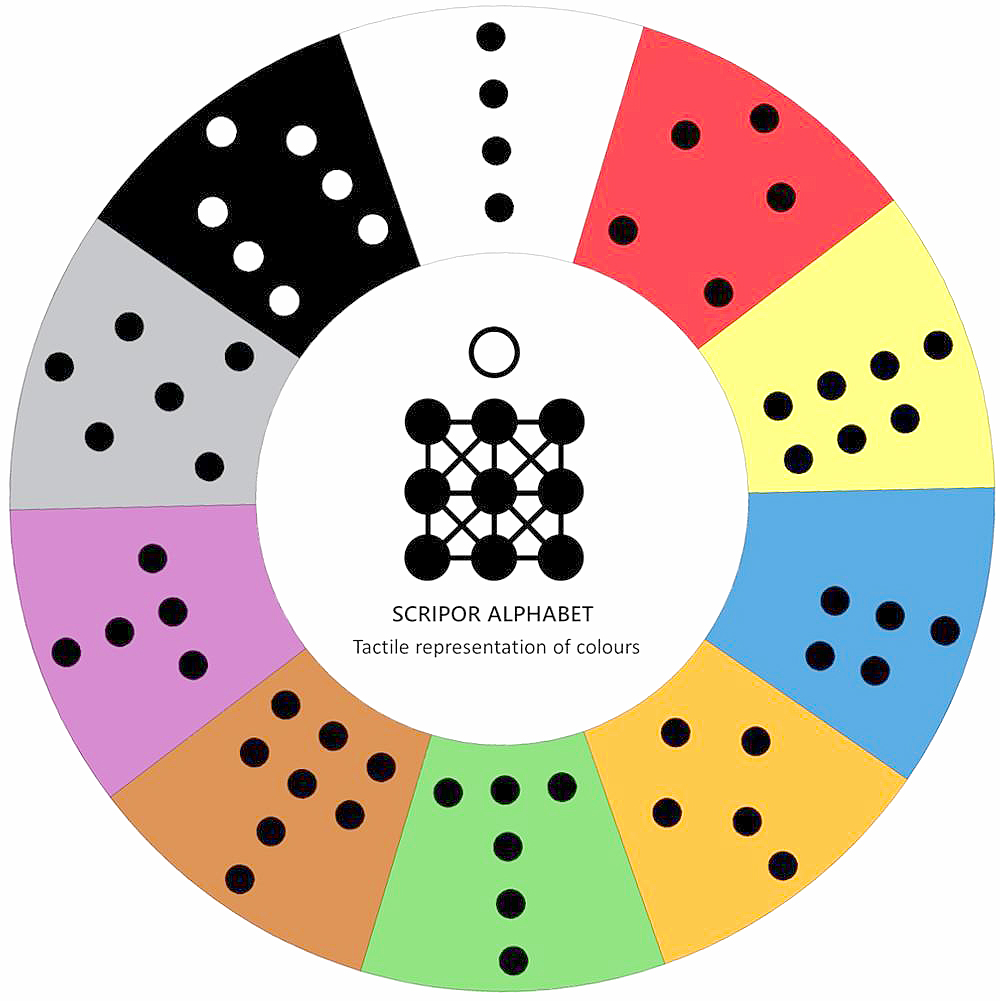

The solution did not come up overnight, but over seven years, Scripor developed the Scripor Alphabet, a tactile system that adapts the logic of Braille to the domain of colour. Scripor invented an alphabet that consists of a 10-dot cell, a 3×3 grid plus an orientation point, encoding a specific colour. Additional cells can express tints, shades, tones, and intensity, allowing users to read not only “blue” but also how light, dark or saturated that blue is. Because it encodes colour as touchable structure rather than language, the alphabet is universal, which makes sense across languages, cultures, and geographies just like the Braille alphabet, it is the “Braille of colours”.

How do you explain a colour to someone who has never seen it? With the Braille of colours.

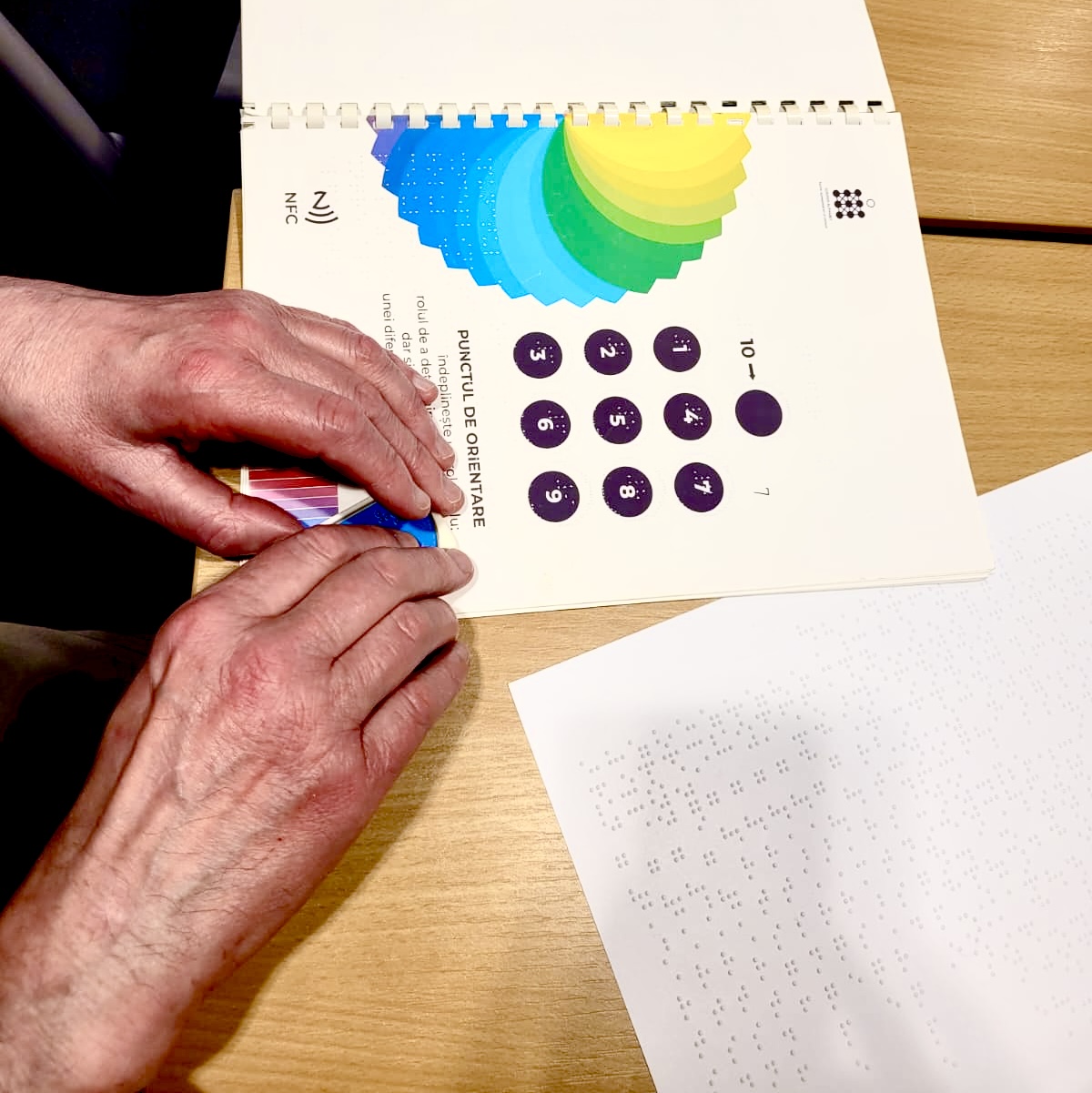

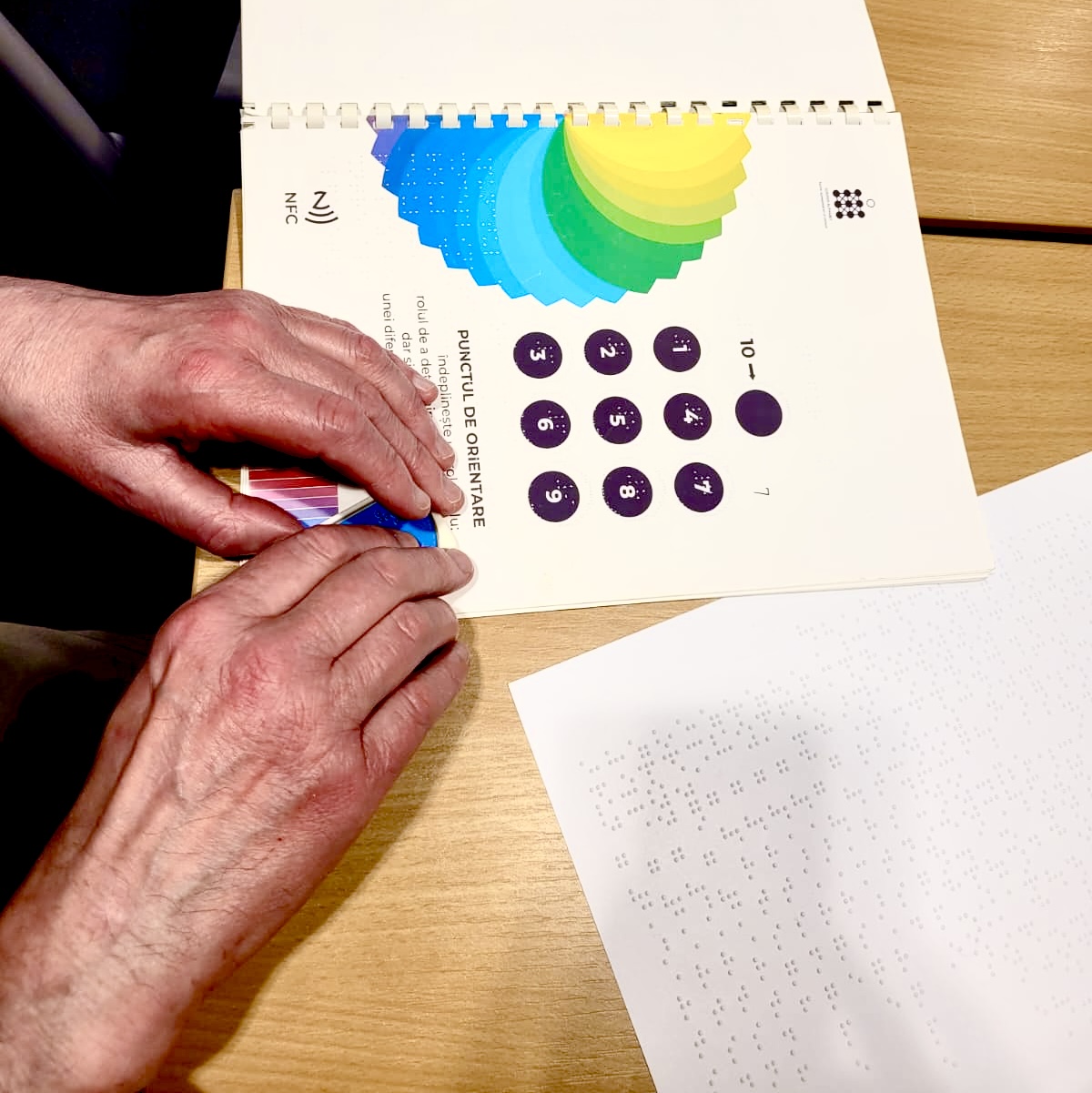

Scripor didn’t build the system in a vacuum. “Nothing for us, without us” he says. The alphabet matured through co-creation with blind users, iterative prototyping, and constant testing. There were dead ends and revisions, but also moments of quiet breakthrough, like the day participants used tactile labels to identify the colours of their own clothes without assistance. That was the proof: inclusion could be felt.

Why Intellectual Property mattered

From the outset, Scripor saw the alphabet not merely as an invention but as a right: a tool that should exist reliably and consistently for everyone who needs it. He chose patents and trademarks to protect the technical solution and its brand, as well as the integrity and quality of his invention. Through IP protection he could prevent any distortion and signal the brand's credibility. “Unprotected innovation is fragile” he notes. “Intellectual property is not only about defending innovations, it is also a bridge. A bridge that builds trust and carries ideas into the world.”

In practice, that bridge serves three purposes. First, it assures governments, organisations, and companies that they are adopting a system with clearly established authorship and standards. Secondly, it invites collaboration and licensing, because partners know there is a framework ensuring fidelity and consistency. Finally, it enables the alphabet to scale without splintering, a common risk for inclusive tools once they gain visibility.

Unprotected innovation is fragile. Intellectual property is not only about defending innovations. It is also a bridge that builds trust and carries ideas into the world.

Destined to help the blind

Protecting a tactile colour alphabet was, by definition, unprecedented. Scripor had to prove to examiners that the system was novel, inventive, and clear, which meant assembling prototypes, documentation, and user evidence across jurisdictions. The legal path was fragmented, each country brought its own procedures, timelines, and translation burdens. The COVID period added further delays, slowing institutions and correspondence. Financially, it was demanding. As an independent inventor, Scripor paid all costs not only in terms of money, but also through investing his time. The process required more than paperwork; it required resilience, patience, and faith that the idea would bear fruit, as well as cooperation with Intellectual Property (IP) professionals to ease his challenges in finding a way to overcome administrative and legal issues.

There were human moments, too. Naming the system felt elusive until a colleague said, “Braille was named after its creator; Morse after his. Why not yours?” Later, the President of the European Inventors Association wrote to him, affirming the significance of that identification and pointing out that the word “script” in Latin means “writing/alphabet”, a fitting echo in the inventor’s own name, Scripor. Was it another coincidence or a destiny? Was he born to invent this alphabet for the blind?

From protected concept to shared standard

The Scripor Alphabet is now finding its way into books and educational materials; clothing labels and packaging; museums, toys, and board games; assistive technologies and smart devices. “Inclusion must be lived. It is joy. It is belonging” Scripor recalls, thinking of a child who asked for games that blind parents and sighted children could play together. The alphabet is designed to be learned in minutes and to work with both hand embossing and modern printers, making it practical at home and industrial scale alike.

Inclusion must be lived. It is joy. It is belonging.

To grow responsibly, Tudor Scripor is building an IP licensing ecosystem underpinned by patents, trademarks, and copyrights. The aim is not gatekeeping but guaranteeing authenticity and consistency, so that thousands of products can carry the code with confidence: trust for institutions; reliability for companies; and predictability for users and families.

IP with a soul

Scripor’s advice is simple and hard-won: protect early, not to lock an idea away but to let it grow safely and keep the purpose in view: dignity and independence for end users. “If your invention serves people, protecting it through IP is more than a legal step. It is an act of responsibility” he says.

If your invention serves people, protecting it through IP is more than a legal step. It is an act of responsibility.

The Scripor Alphabet didn’t emerge from privilege or a corporate lab; it came from perseverance, empathy, and collaboration. Tudor Scripor knows it: IP didn’t weaken that spirit; it strengthened it, turning a fragile idea into a reliable standard that can be used across countries and industries without losing its soul.

Images: Courtesy of Scripor.

This Case Study was created under Creative FLIP, an EU co-funded project aimed at further increasing the long-term resilience of the CCSI in key areas such as Finance, Finance, Learning, Working Conditions, Innovation & Intellectual Property Rights.

Key Takeaways

- IP as enabler: Protecting the invention and the brand name with patents and trademarks preserves integrity, signals credibility, and unlocks scalability.

- User-centred proof: Co-creation with blind users turns a human need into a robust, protectable invention.

- IP and licensing for impact: A structured IP licensing approach increases the ability to exploit IP assets while safeguarding their quality across sectors and across borders.