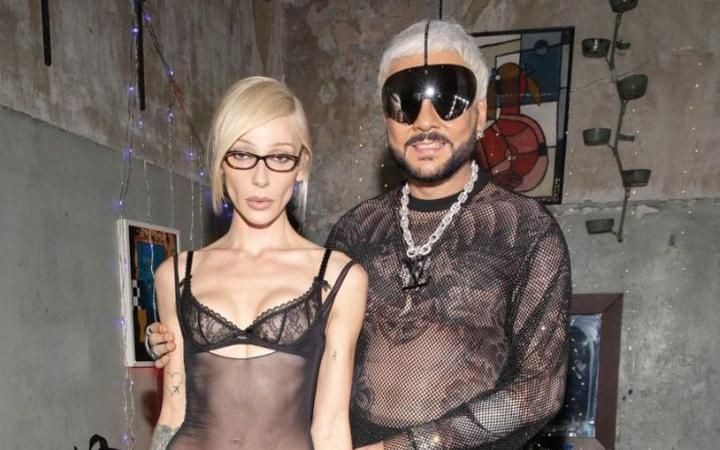

The new year had barely begun when a scandal erupted in Moscow's nightclubs. Pop star Anastasia Ivleyeva had hosted a raunchy 'Almost Naked' party, prompting outrage from nationalist bloggers and politicians. Within days, the festivities turned sour as Ivleyeva and guests like rapper Vacío faced hefty fines and even jail time on dubious 'morality' charges. For the Kremlin loyalists who helped prosecute the case, the party flaunted values of "modesty, restraint and sacrifice" needed in a time of war.

However, analysts saw the crackdown as driven less by piety than politics. As Russia's economy sputters under sanctions, restricting lavish lifestyles channels discontent over hardships at home onto foreign enemies like liberal elites. The party raid "violated the sacred rules of how a person should behave in wartime," as Andrei Kolesnikov, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center told Politico, likening it to recent mutinies by figures like mercenary leader Prigozhin that challenged Vladimir Putin’s authority. The only naked party punishments confirmed a turn that had been taken earlier.

In April 2023. The Russian and English-language independent news website Meduza reported that Vitaly Borodin, head of the Federal Security and Anti-Corruption Project, had asked Russia's Prosecutor General to open a criminal case against actress Liya Akhedzhakova. He claimed that Akhedzhakova had criticised "the decisions and policies of state bodies and the president regarding the Russian invasion of Ukraine" and accused her of "treason" and "discrediting" the armed forces. Akhedzhakova denied the charges. Borodin recommended that Akhedzhakova be labelled a "foreign agent." As a result of these accusations, she was forced to leave the Sovremennik theatre, where she had worked for many years.

The Kremlin’s attitude toward the showbiz elite has worsened since that incident. Artists and music stars who stayed in Russia and kept out of the political fray were at first rewarded with lucrative deals or, at least, left alone. However, those days are over, and the impunity of the elites looks like a political liability for Putin he cannot afford.

In a severe cultural purge, the long-time partygoers have become the target of the government. Their concerts have been cancelled, and scenes featuring them were removed from state television shows and films. Moreover, their names have been scrubbed from promotional material. A Russian version of Cancel Culture…

A war on the cultural front

Meanwhile, beyond Russia's borders, the culture wars rage on. New reports reveal Moscow holding intense negotiations to expand its global Cultural network, with Algeria, Saudi Arabia and the UAE for new ‘Russian House’ centres. Modelled after France and Poland's acclaimed cultural institutes, these hubs have long spread pro-Kremlin soft power from Europe to Central Asia. Russia is also negotiating to open additional cultural centres in Brazil, South Africa, Angola, and Mali by 2025. However, concerns are growing over how Russia may now use them to justify its assault on Ukraine and expand censorship abroad.

Last year, a ‘Russian House’ in Prague stoked backlash by distributing war-promoting books, triggering a sanctions probe. As several analysts have shown these institutions work to “support the Russian regime and its expansionist policies” by framing the conflict as a civilisational clash beyond Putin. Yet it is also a tool under increasing strain. Russia's cultural diplomacy is carried out by state-affiliated or full-fledged state organizations such as Rossotrudnichestvo, the “Russkiy Mir” Foundation, and the Gorchakov Fund.

As the Kremlin cracks down on Artists at home, it faces growing resistance to exposing Russians and Ukrainians abroad. After Kyiv made clear its citizens would boycott any shared events, the New York literary festival PEN America was forced to cancel a panel featuring dissident writers from both countries, something it apologized for, later. While some Ukrainians still perform with anti-war Russians overseas, they seem to do so solo or face a huge backlash from the cultural establishment.

With weapons now more important for garnering foreign attention than artistic talents, Ukrainians perceive any Russian presence as appropriating focus from their wartime plight. As Katerina Sergatskova explains in this article for many Ukrainians "classical and contemporary Russian literature, cinema, music, theatre, etc." aided the nationalist project leading to destruction in Ukraine. But exiled Russians may find fewer international platforms as the cultural tide turns against them too. Many question if this new "Ukrainian cancel culture" could set a troubling precedent for the post-war era. It poses difficult questions about reconciling wartime imperatives with liberal principles of Artistic freedom and open debate.