By Connor Findley

France and Japan have a unique history of cultural exchange, going all the way back to the 19th century. For almost 300 years, Japan had been ruled by the

Tokugawa Shogunate under an exclusionist policy that forbade nearly all international relations. When the country was reopened to foreign trade in 1852, many European artists were starstruck by the wholly unique

styles on display in Japanese cultural products. Several influential painters from this time period, Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, and Paul Gaugin among them, began to experiment with Japanese creative elements in their own art. Examples can be found in Monet’s

La Japonaise, which features his wife Camille in Japanese costume, or Gaugin’s

Personnage Japonais sketches. Japanese wood-block prints or ukiyo-e were particularly strong influences, and Monet and Vincent van Gogh both curated large personal collections. While living in the French town of Arles,

Van Gogh was even quoted as saying, “All my work is based to some extent on Japanese art.” Some of these works are originals, such as

Portrait of Julien Tanguy, while others are copies of Japanese woodcuts, like

Flowering Plum Orchard (copy of Japanese print Hiroshige).

The sudden emergence of Japan’s distinct culture in Europe and its enthusiastic reception by well-known artists turned out to be the perfect storm. Not just visual art, but Japanese theater, poetry, fashion, and more came to be considered la mode in France throughout the late 19th century. The movement would be called japonisme, and would cement a fascination with Japanese culture into the French consciousness. Likewise, Japan’s culture underwent an unprecedented period of reinvention and modernization, taking influence from French art just as its own art was changing French perceptions. It’s perhaps the very fact that the Japanese and French approaches to art and culture were so different from one another that led to their unusual magnetic attraction. Sophie Basch, a professor in Paris specializing in japonisme, told The Japan Times, “At the time, French artists, coming from the Impressionist movement, were searching for a certain modernity…. For them, [ukiyo-e] represented a form of liberation, with daring compositions and bold colors.” Japanese ideas reinvigorated the French art world at a key point in history, setting the stage for japonisme’s more modern incarnation in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

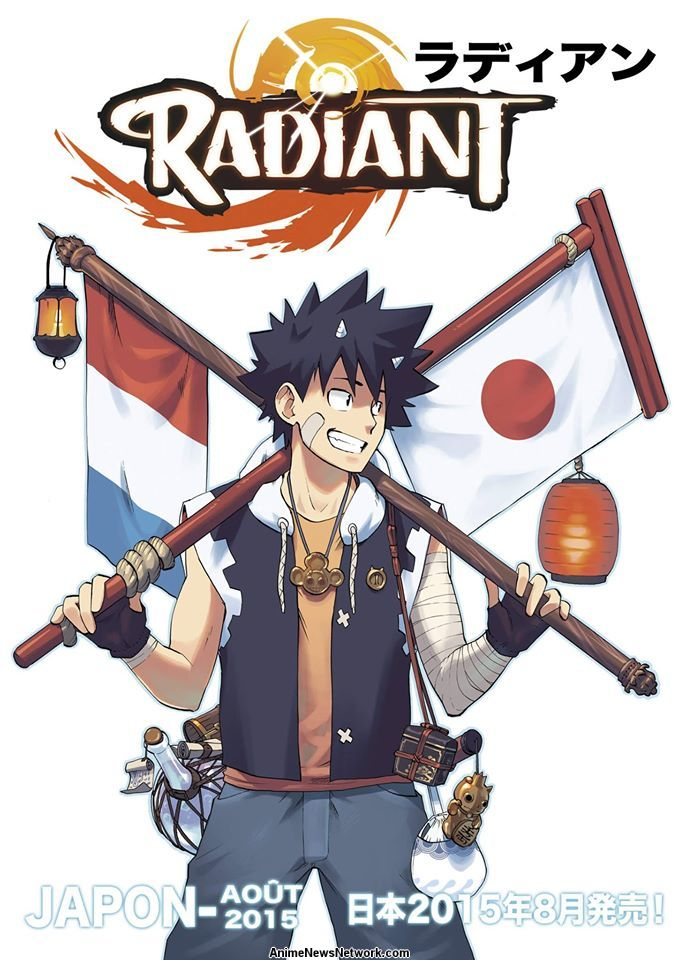

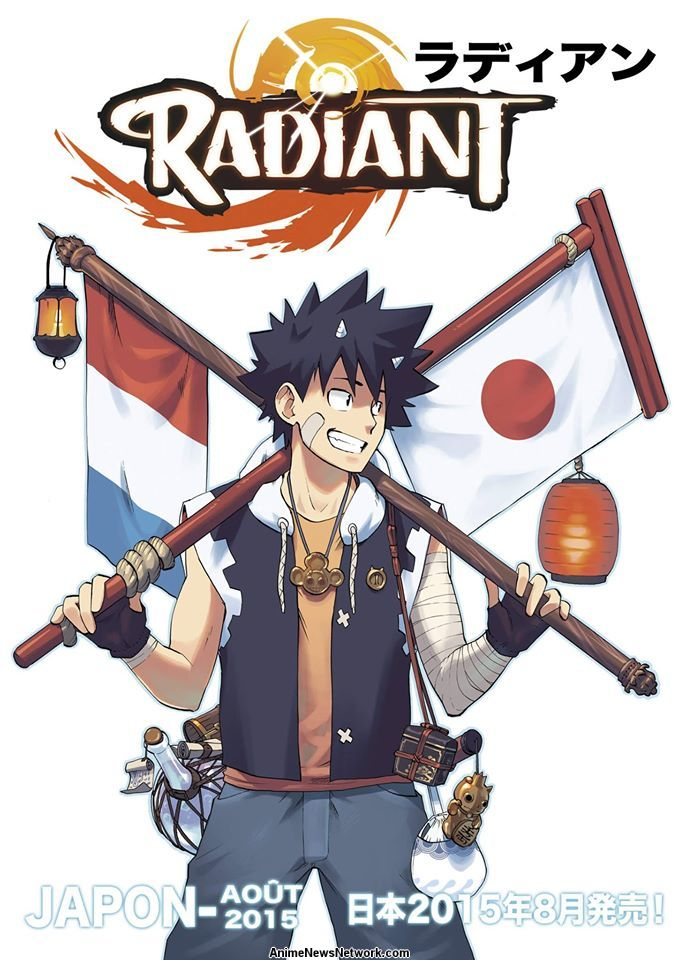

Néo-Japonisme

Japonisme has proven to not just be a one-and-done trend in France’s history. On the contrary, modern Japanese culture has been enjoying a resurgence in popularity among the French since the latter half of the 20th century, and only continues to grow in significance. France has the world’s second-largest market for manga (Japanese comics) in the world, and cultural events in France such as the annual Japan Expo in Paris attract hundreds of thousands of participants each year. French tourism in Japan and Japanese language-learning remain quite popular, as do exhibitions of classical and modern Japanese art, such as at the Maison de la Culture du Japon à Paris (MCJP) just off the banks of the Seine. There is even a budding industry of Japanese-inspired French comics, which are often referred to with the portmanteau “manfra” (manga + France).

Image credit: Anime News Network promotional image for “Radiant,” a manfra series by Tony Valente

As in the late 19th century, is it that same distinction from their own culture that makes Japan so fascinating to the French in the 21st? There may be something else at play—to many current Japanophiles, it’s not only exoticism that attracts them to Japan, but a sense of kinship and familiarity. Manga and anime, the stylistic successors to the ukiyo-e prints of the early japonisme movement, were important childhood fixtures for many French people who grew up in the 1980s and 90s. During this period, French television broadcasters often turned to localizations of popular Japanese animated shows, or “anime,” due to their low production costs and diverse genres. Consequently, many in France were exposed to anime hits like Dragon Ball Z and Sailor Moon from an early age. In the 90s, following the commercial success of anime in France, manga made its way into the bandes dessinées market (bandes dessinées being the French term for graphic novels), also becoming wildly popular.

However, this isn’t to say that what we could call néo-japonisme had a breezy start in France. The French cultural anthropology scholar Clothilde Sabre wrote that many adults in the 80s and 90s, “denounced the violence, mediocrity, silliness, eroticism and general ‘harmfulness,'” of the anime series that were broadcast in France, “precipitating moral panic regarding manga imports for many years.” French parents flew into a panic at the same exoticized cultural paraphernalia that their children would later develop a passionate nostalgia for. Often called the “Club Dorothée Generation” after a popular anime from the time period, these viewers, now young adults, would herald the more positive perception of Japanese media that you see in France today.

Author’s photo: A selection of home video anime series in an apartment complex in France

Motivated by this combination of familiarity and fascination for the foreign, many modern French fans find themselves longing for a deeper, more authentic connection to Japan. A visitor to Japan through the French tourism company Autrement le Japon (see Clothilde Sabre’s work for the full quote) put it this way: “Reading manga allowed me to learn a lot about everyday life and Japanese youth (especially high school life, which was the stage my life was at in France at the time)…. But as much as I love manga and anime, it was no longer enough to know Japan only through these images from the media…. I said to myself: ‘I should go there to see it for myself.'” Japan figures as a familiar country for the French who grew up with its media, but also as a place of wonder and exploration which media can only scratch the surface of, begging for discovery and a more authentic understanding.

Opposites—and Birds of a Feather—Attract

After all, the kinship that the French feel with Japan may not just be the result of globalization and media exchange. The two countries, as different as they are, have many fundamental values in common. They each put a high value on artistic expression, language, and cultural traditions, while at the same time exemplifying these values in diverging ways. There is both a shared basis for connection, and an inspiring diversity of goods and ideas to exchange between France and Japan. Manga and bandes-dessinées turn out to be a great analogy: France and Japan both have a shared cultural “language,” but each has something new to learn and love in the other’s approach.

It is tempting, when envisioning France, to think only of its own rich history and culture. But a significant and growing part of that French culture is defined by how it crosses over with the rest of the world, and particularly how Japanese aesthetics and ideas are intertwined with France’s past and present. As artistic collaboration and cultural exchange between the two countries continue to grow, japonisme will likely stick around to remind us of the importance of thinking internationally as Francophiles.

--

The original article first appeared at frencjly.com. You can read it here

Connor Findley is a sophomore at Rice University studying English. When they aren’t writing essays, they’re playing French translations of video games or futon-philosophizing.