Profile: Laurens von Oswald, co-founder of Berlin Atonal

By: Hester Underhill

The first edition of Atonal festival in 1982 was legendarily explosive. At Kreuzberg club SO36, acts took to the stage armed with scrapyard junk, untuned guitars and drills — clanging and whirring to create a new breed of experimental music that was dubbed by the press the “Berliner Krankheit” (Berlin illness). Far from the polished pop of erstwhile chart-toppers like ABBA, these raw sounds encapsulated the sense of wild nihilism felt by West Berlin youth at what felt like a particularly hopeless time in the city’s history.

This first edition of Atonal proved a pivotal moment for Berlin’s music scene, acting as a launchpad for various era-defining groups such as Einstürzende Neubauten and Die Haut. But its influence also reached far beyond the city, thanks in part to British DJ John Peel who raved about the event on his highly influential radio show. The festival would only run in different venues around the city until 1990, when founder Dimitri Hegemann turned his attention to founding the now-legendary techno club Tresor.

The festival’s revival came in 2013, when Hegemann passed the baton to a new generation of sonic pioneers. “I had just arrived in Berlin and was working as a kind of intern at Berghain when I was introduced to Dimitri,” says Laurens von Oswald, who had come to the city shortly after finishing his journalism degree in London. German-born von Oswald had emigrated to Australia with his parents as a child before heading to the UK for his studies. “I sort of fell into music during that time. It was a really special moment to be in London, a pivotal moment before everything started to become prohibitively expensive. You would go out and hear music you’d never heard before and you’ll probably never hear again. So that’s where my fixation landed, rather than on my studies. I realised that music was what I wanted to put my energy towards.”

It was clear, however, that the moment wouldn’t last. With London clubs quickly shuttering, Berlin seemed like the clear alternative for anyone wanting to work in electronic music. Hegemann invited von Oswald to the Tresor office and it wasn’t long before the two realised they had much in common. “He gave me a tour of Kraftwerk, which was very much still a ruin at that time. He told me he used to do a festival here in the 80s. I said I’d never thought about doing a festival before, and he suggested I give it a go. And the next day it began. We assembled a small team and started working on it.”

That group included Harry Glass, an old friend of von Oswald who still runs the festival with him today, and Paolo Reachi, who had been running Tresor Records and left the Atonal team in 2020. The first edition was a baptism of fire. Being new to the city, von Oswald had to figure a lot of things out for himself. “Dimitri is a total visionary. He’s someone who is very good at supporting ideas and encouraging things, but he’s not someone who is going to hold your hand. But that’s kind of the good thing about being in your early twenties. You’re ignorant about a lot of things, so you just give them a go.”

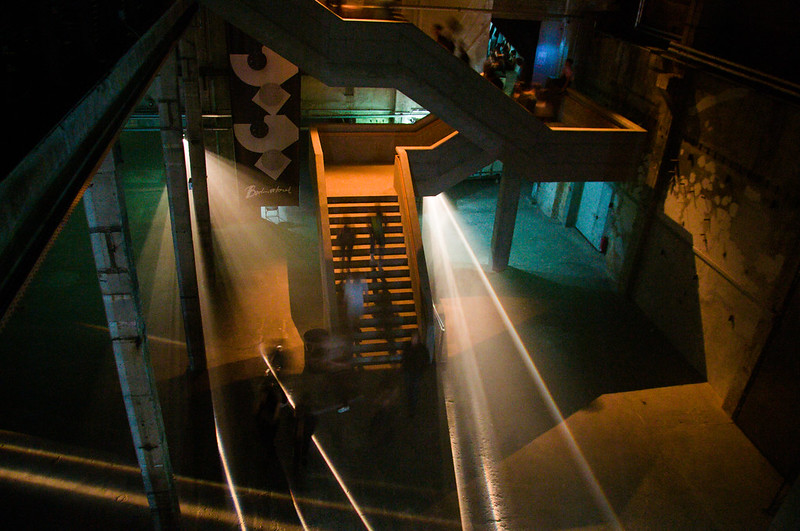

Over the years, von Oswald and his team have transformed Atonal from a revived underground experiment into one of the world’s leading festivals for experimental music and audiovisual art. Held annually in the cavernous, former power station of Kraftwerk Berlin, the festival has grown in both scale and ambition, attracting a global community of artists, musicians, and audiences eager to witness the bleeding edge of sound and performance. What began as a risky passion project is now a meticulously curated program that balances avant-garde innovation with historical reverence, often featuring legendary pioneers alongside emerging talent.

"Over the years, von Oswald and his team have transformed Atonal from a revived underground experiment into one of the world's leading festivals for experimental music and audiovisual art."

Since the pandemic struck, the festival has existed in a shape-shifting format. “In 2020 we took a very welcome break. It was such a unique moment of being able to stop, and look around and think, what are we doing? Especially in the world of culture. We never got much scope for reflection, like you finish one festival and you immediately start planning the next one. So automatically you arrive at these repetitive patterns without even really thinking about it. So the pandemic was a chance to interrupt that.” In the years following the covid shutdowns, each iteration of the festival has taken a different form. “We’ve been experimenting with different modalities — how the audiences experience art works and how the spaces get used.” Von Oswald and his team have also organised various exhibitions as part of the festival; one on the history of Tresor and another on avant-garde Greek composer Iannis Xenakis. This year will see a return to the festival’s pre-covid format, with three days of music at Kraftwerk in August.

Despite the Atonal’s growing reputation, maintaining its independent spirit in an increasingly commercialised city hasn’t been easy. Berlin, once a haven for artists seeking freedom from market pressures, is no longer the affordable creative utopia it once was. “It’s not cheap anymore at all,” von Oswald notes. “The cultural offerings here have become prohibitive.”

When he first arrived in Berlin, von Oswald was drawn by the same forces that had attracted generations of creatives before him: space, affordability, and the promise of artistic autonomy. “What made Berlin attractive — and ultimately, why it’s such a special place — is because artists live here. Artists interested in pursuing an alternative kind of structure for their lives, being able to focus on their work without sacrificing comfort.”

"What made Berlin attractive — and ultimately, why it's such a special place — is because artists live here. Artists interested in pursuing an alternative kind of structure for their lives, being able to focus on their work without sacrificing comfort."

For Atonal, the tightening economic conditions have had tangible consequences. The festival has never received consistent institutional support, and each edition is a feat of financial navigation. “We've always been in this very precarious situation,” von Oswald says. “You can't apply for funding more than a year in advance. The funding we had committed for this year’s festival was halved at the end of last year without any explanation or warning.”

It’s a common story among Berlin’s remaining independent cultural spaces — caught between international acclaim and local indifference, thriving artistically while struggling logistically. “There are more people than ever trying to work as artists or musicians,” von Oswald reflects. “But there are far fewer outlets for that than there were 10 years ago. Fewer clubs, fewer festivals. Or fewer good ones, at least.” Still, against these odds, Atonal continues. More than four decades on from its scrappy origins at SO36, the festival remains a platform for what’s next — even as the ground beneath it constantly shifts.

Images:

1. Atonal at Kraftwerk / Tresor, Berlin, August-2015, CC BY-SA 2.0

2. Courtesy of Laurens von Oswald