The creative industries, including music, film, publishing, and advertising, are being significantly impacted by the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies. AI is enabling new creative possibilities, such as AI-generated art, music composition, and scriptwriting. However, it also raises concerns about copyright, ownership, and the role of human creators.

It is transforming creative workflows and business models in the industry, opening new challenges around the use of AI in creative work, such as ensuring transparency, accountability, and fair compensation for human artists whose work is used to train AI systems. But it goes even deeper than that: scholars and practitioners now find themselves grappling with a critical examination of the very nature of creativity itself.

Is creativity a function of human labour and expression, or can it be reduced to mechanical processes and capital? The discussion invites a deeper exploration of the political-economic dimensions of creativity, as well as the fundamental question of its origins - whether it stems from the unique spark of human genius or can be replicated through technological means.

As AI technology advances, producing increasingly sophisticated and human-like creations, distinguishing between artworks crafted by human hands versus those generated by algorithms has become an ever more daunting task. Several methods have been proposed to differentiate the two, such as artist disclosure and the use of specialized software. However, these approaches hinge on the honesty and transparency of the creators, presenting an inherent challenge as AI continues to evolve.

This quandary lies at the heart of the ongoing discourse surrounding the implications of AI for the creative sector.

The promise and peril of AI integration

An ENCC report opens the discussion about how the sector should adopt and introduce generative systems in creative practices and what it would mean. The Network had previously authored an edition on Digital Ethics for Cultural Organizations, which brought attention to some of the pressing issues in the digital realm.

An ENCC report opens the discussion about how the sector should adopt and introduce generative systems in creative practices and what it would mean. The Network had previously authored an edition on Digital Ethics for Cultural Organizations, which brought attention to some of the pressing issues in the digital realm.

"it is clear that AI has the potential to radically transform the way the cultural sector operates. I see this new AI wave as both a remarkable opportunity and a sizeable threat to cultural workers’ welfare and rights," warns Romain Boonen, founder of Empowork Culture.

From environmental concerns about data-hungry systems to fears of job displacement and threats to creative autonomy, the cultural sector is grappling with an AI revolution that could reshape its very fabric.

"What kind of societal missions do we want, exactly, from culture and the arts? Is it thinking against the grain, investing in the marginal, experimenting with uncharted paths, and harvesting unexpected results, sometimes with no tangible results at all? If it is, how much help can AI be?" asks Lucy Perineau, freelance illustrator and digital ethics coordinator for the ENCC.

Boonen envisions a future in which technology "could decrease the mental burden associated with some of our more repetitive tasks" in the cultural sector, freeing up workers to focus on more creative and strategic activities.

"It has the potential to change the nature of most of the cultural workers' daily tasks, allowing for far more creative and strategic thinking across organizations, thereby decreasing the nitty-gritty aspects of pure execution and allowing for more high-level, intention-driven decision-making across organizations," he says.

However, Lucy Perineau is cautious about this productivity-driven logic, warning that it may be at odds with the core social missions of cultural institutions.

"I understand the desire for time-strapped cultural workers in the Global North to decrease repetitive, tedious tasks. The thing is that the logic pushing for a takeover of “meaningless” tasks by machines (and in fact by low-paid workers in less privileged regions, which engage in some of the most repetitive and tedious tasks in the world) seems currently inseparable from the language and tactics of “productivity gains," “net benefits," “added value," “sectorial attractiveness,” and so on. This vocabulary leaves little space for cultural workers to move on to high-level creative and strategic thinking because the orientations and strategy are already massively defined by built-in productivity and profitability goals. Which are not necessarily the mission of cultural organizations.".

"I understand the desire for time-strapped cultural workers in the Global North to decrease repetitive, tedious tasks. The thing is that the logic pushing for a takeover of “meaningless” tasks by machines (and in fact by low-paid workers in less privileged regions, which engage in some of the most repetitive and tedious tasks in the world) seems currently inseparable from the language and tactics of “productivity gains," “net benefits," “added value," “sectorial attractiveness,” and so on. This vocabulary leaves little space for cultural workers to move on to high-level creative and strategic thinking because the orientations and strategy are already massively defined by built-in productivity and profitability goals. Which are not necessarily the mission of cultural organizations.".

"The logic pushing for a takeover of “meaningless” tasks by machines (and in fact by low-paid workers in less privileged regions) seems currently inseparable from the language and tactics of “productivity gains," “net benefits," “added value," “sectorial attractiveness,” and so on - Lucy Perineau, digital ethics coordinator for the ENCC

Securing creative autonomy

Beyond concerns about working conditions, there are fears that the rise of AI could directly threaten the very nature of cultural production. Some observers worry that AI could undermine artistic output's quality, originality and diversity, ultimately harming plurality and independent culture.

"I share these concerns," says Boonen. "AI should serve and support human agency, not deprive us of it. It goes back to my previous point about automation vs. augmentation: every cultural organization and worker will have to find the right balances, but it seems clear to me that failing to empower people to use their human agency through the use of these tools will result in a blow to the originality of our collective cultural output."

--

Toward a Human-Centric Approach

As the cultural sector navigates these uncharted waters, the ENCC report calls for a proactive, critical and human-centred approach to AI integration. This means demanding transparency, advocating for worker-friendly policies, and fostering a deeper understanding of the technology's capabilities and limitations.

The report also examines the EU's AI Act, a regulatory framework that aims to establish guardrails for responsible AI development. While seen as a step in the right direction, concerns remain about whether a truly 'human-centric' approach can be achieved. For Perineau, the way forward requires a fundamental reassessment of the sector's priorities.

"Now is the perfect time to take on this daunting challenge," says Boonen. "Collectively, we have the power to shape the future of what it means to work in culture."

--

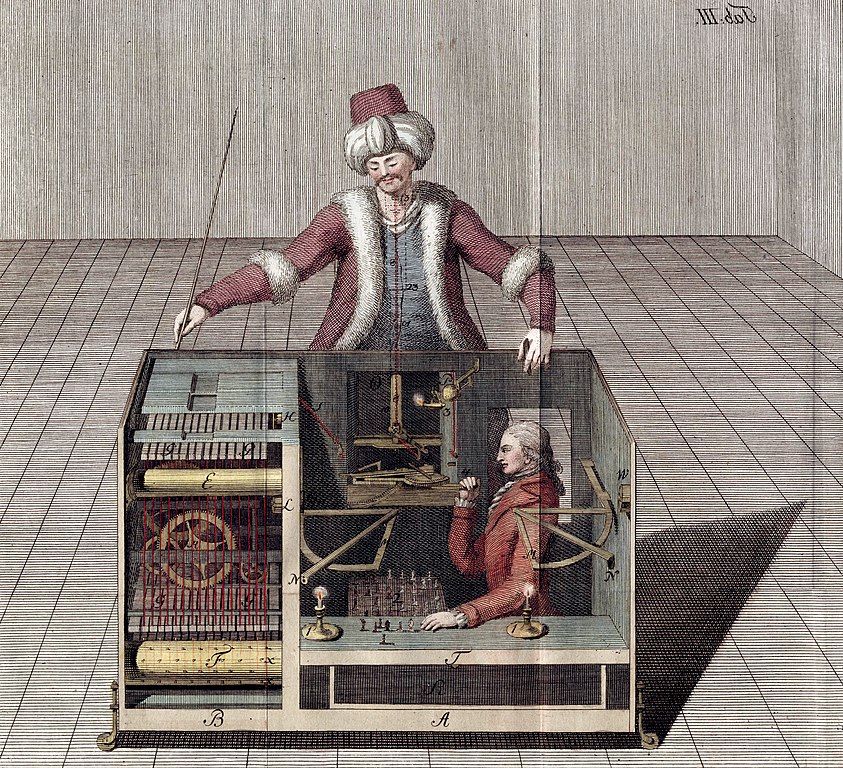

Image: Joseph Racknitz - Humboldt University Library, Public Domain

An

An  "I understand the desire for time-strapped cultural workers in the Global North to decrease repetitive, tedious tasks. The thing is that the logic pushing for a takeover of “meaningless” tasks by machines (and in fact by low-paid workers in less privileged regions, which engage in some of the most repetitive and tedious tasks in the world) seems currently inseparable from the language and tactics of “productivity gains," “net benefits," “added value," “sectorial attractiveness,” and so on. This vocabulary leaves little space for cultural workers to move on to high-level creative and strategic thinking because the orientations and strategy are already massively defined by built-in productivity and profitability goals. Which are not necessarily the mission of cultural organizations.".

"I understand the desire for time-strapped cultural workers in the Global North to decrease repetitive, tedious tasks. The thing is that the logic pushing for a takeover of “meaningless” tasks by machines (and in fact by low-paid workers in less privileged regions, which engage in some of the most repetitive and tedious tasks in the world) seems currently inseparable from the language and tactics of “productivity gains," “net benefits," “added value," “sectorial attractiveness,” and so on. This vocabulary leaves little space for cultural workers to move on to high-level creative and strategic thinking because the orientations and strategy are already massively defined by built-in productivity and profitability goals. Which are not necessarily the mission of cultural organizations.".