In Serbia, the use of spyware against Journalists has escalated since 2023 amid political crises and public demonstrations. In Turkey, over a million online content items were blocked last year, including 5,740 news items or media websites. Big tech companies have increasingly complied with Turkish government demands, prioritising profit over press freedom and freedom of speech. And in Denmark, the proposed Media Ombudsperson would have significant powers, including the ability to report defamation and libel cases to the police, intervene in civil cases, and refer matters to the Press Council. Press associations fear that these powers could undermine the separation of powers and lead to censorship or self-censorship.

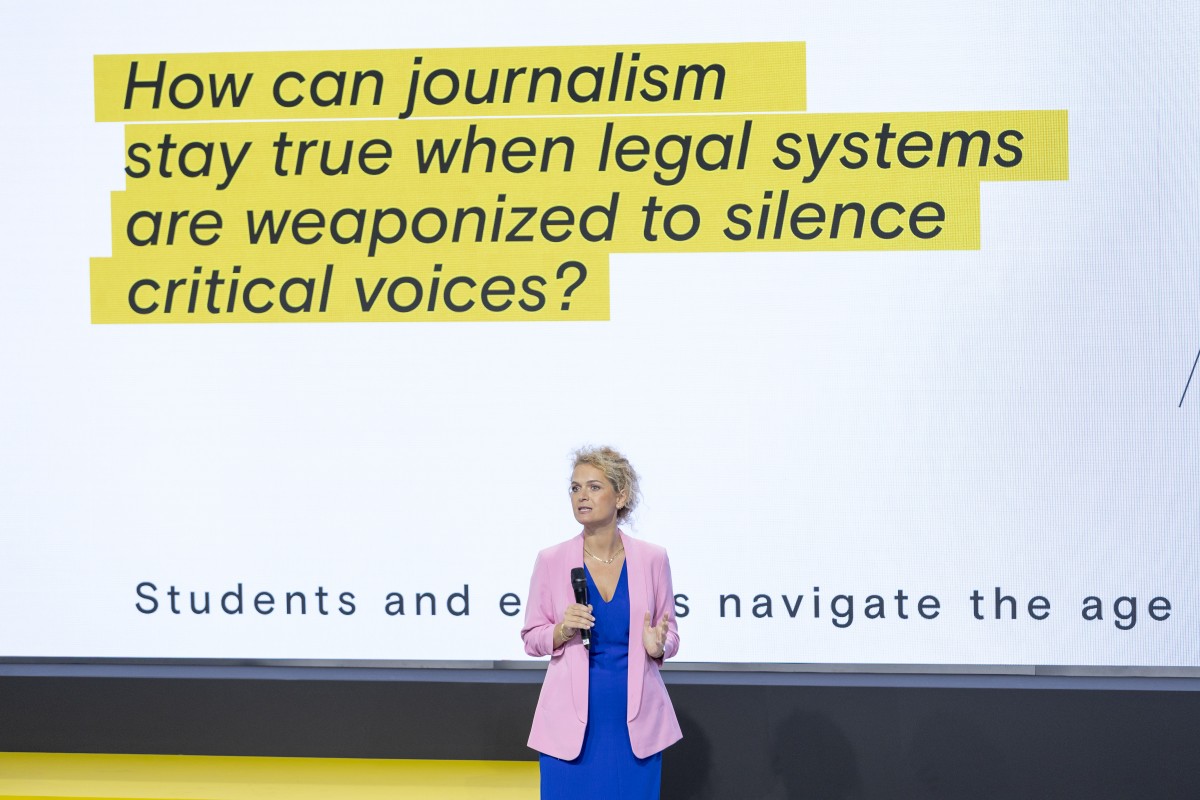

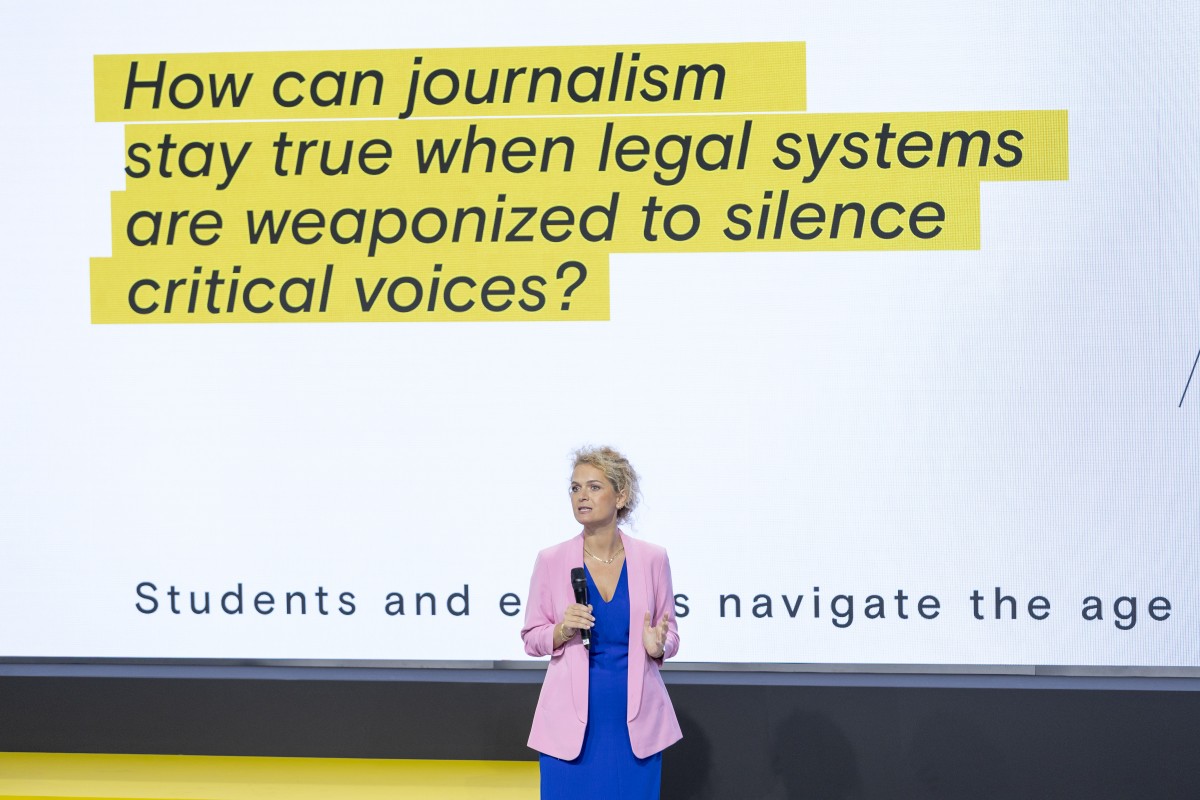

These are some of the threats to press freedom in Europe that were discussed at the Media Freedom Rapid Response (MFRR) 2025 last week in Brussels (October 13). The conference, organized by the European Center for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF) as part of the Media Freedom Rapid Response (MFRR) monitoring and reporting mechanism in EU member states, candidate countries, and Ukraine, recorded more than 1,500 violations across the continent in 2024. These included police violence against journalists at demonstrations, online smear campaigns and digital intimidation, threats to life, etc.

The summit also addressed the economic challenges facing the media industry, including platform ad monopolies, collapsing business models, state funding bias, and increased far-right influence.

However, there is some positive news. With the introduction of the Anti-SLAPP Directive and the European Media Freedom Act (EMFA), the summit emphasised the importance of implementing protective laws based on the EMFA in national frameworks to ensure they effectively safeguard free and independent journalism.

In this interview with Creatives Unite, Flutura Kusari (Senior Legal Advisor at the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF) and Elena Rodina (MFRR Coordinator at the ECPMF) discuss new threats to journalism across the world and in Europe, such as the spread of 'foreign agent laws' in different European countries. Modelled on Russia's "foreign agents" law, these laws are being used to stigmatise and pressure critical journalists, ultimately threatening media freedom and democratic participation.

The summit coincided with the discussion of the EU Democracy Shield policy, emphasising the importance of journalism as a cornerstone of democratic infrastructure. Against the backdrop of the deadliest attacks on journalists in the Middle East by Israel, the ongoing war in Ukraine and the unresolved murders of Daphne Caruana Galizia and Giorgos Karaivaz, the two activists emphasise the importance of safeguarding journalists' freedom in Europe as a foundation for press freedom worldwide.

"Lately, we see spoofing and AI-based attacks on journalists. For example, malicious actors create fake profiles, clone journalists' images or voices, and use AI to make it appear that the journalist said or did something they never did." - Elena Rodina

CU: We’re used to thinking that Europe guarantees freedom of the press — but is that still true? What are the main challenges for journalists and the media in our continent right now?

Elena Rodina: Our latest report, which covers the first half of 2025, already lists over 700 violations. That’s a very high number, and the trend is clearly increasing both in quantity and in severity. Legal threats, in particular, are growing and evolving. Leaders in countries with authoritarian tendencies are learning from each other — and even from full-blown dictatorships. We consider this cross-pollination of repressive legal strategies to be truly alarming.

CU: When we think of legal threats, we mostly think of SLAPPs (strategic lawsuits against public participation). What is new in that front?

Flutura Kusari: SLAPPs mainly target journalists individually; the goal is to drain their time, energy, and money so they’re forced out of the profession. Now we are facing a new threat. Foreign agent laws attack the entire structure of the media. Many media outlets are registered as NGOs, so they fall under these laws. The consequences are severe: stigma, reduced international collaboration, and an overwhelming administrative burden. Many simply don’t have the funds to meet the bureaucratic requirements these laws impose. So yes, we’re moving into a new phase of repression.

CU: Could you mention a few examples?

Elena Rodina: Slovakia is one, Hungary, Serbia, and several EU candidate countries. A rather stark example is Georgia. Under their new foreign agents law (GEOFARA), for instance, media “foreign agents” are required to submit any information or material they distribute to the Anti-Corruption Bureau no later than 48 hours after publication. The law itself is vague and broadly defined; it is stigmatising and creates legal uncertainty. Moreover, an amendment to the criminal code criminalises non-compliance with GEOFARA, so journalists can face up to 5 years in prison if they fail to comply.

In Serbia, the level of malice and contempt shown by those in power toward journalists is shocking. Since November 2024 railway station collapse in Novi Sad, that led to nation-wide protests, state officials have intensified their targeting critical journalists with smear campaigns. There are physical and verbal attacks, journalists are being surveilled, and are often portrayed as enemies of the state. That’s why we have dedicated a separate chapter to Serbia in our latest Monitoring report.

CU: Why is this happening now to your opinion? And isn’t this exactly the case for European institutions to step in?

Flutura Kusari: They can tell their voters, “We’re just making the media more transparent,” which sounds reasonable on the surface but hides the real repressive intent. It took the European Court of Human Rights ten years to issue a strong ruling on a foreign agent case. By then, more governments had already adopted or proposed similar laws. Our appeal is for the Council of Europe, the European Union, and the OSCE to sit together with civil society and journalists for a real dialogue. We don’t have that right now. And if we keep delaying, in five or six years, these laws will become normalised and they will be everywhere.

CU: How would you classify the different types of threats journalists are facing today? Do you see regional patterns — for example, are the problems in the Balkans different from those in Western or Northern Europe?

Flutura Kusari: The issues differ greatly from country to country. See the Balkans: In Albania, there is a major issue with lack of media pluralism. In neighbouring Kosovo, by contrast, there is pluralism, but there are also constant attacks, including by the Prime Minister himself. In Serbia, you have a combination of media capture, verbal attacks, and legal threats through a foreign agent law (it’s currently suspended).

CU: What new types of threats are emerging our days?

Elena Rodina: Lately, we see spoofing and AI-based attacks on journalists. For example, malicious actors create fake profiles, clone journalists’ images or voices, and use AI to make it appear that the journalist said or did something they never did. We’ve documented this in our recent reports — we even have a chapter dedicated to it. It’s a completely new dimension of threat. And the problem is that by the time you say, “It’s not me,” the damage is already done. And the internet never forgets.

"Politicians don't have to like journalists, and journalists don't have to like politicians — there should be mutual respect for the roles each plays in a democracy. That respect is eroding, not just in our region but globally, including among powerful countries that once set the example." - Flutura Kusari

EMFA and the independence of the Media

CU: What are the key threats we should be paying attention to in Europe right now?

Flutura Kusari: The assassination of journalists. When a journalist is murdered, justice almost always depends on how vocal we are. For example, if the family speaks up, goes public, and advocates internationally, the case stays alive. But doing that requires resources, time, and courage. Look at the case of Daphne Caruana Galizia in Malta. It became a global cause because her son Matthew and her sister Corinne devoted their lives to seeking justice. Without their persistence, it wouldn’t have received the same attention. The quality of democracy is also important in how quickly and transparently justice responds. In the Netherlands, after the killing of Dutch crime reporter Peter de Vries, the authorities immediately portrayed it as unrelated to journalism — which I disagree with saying unrelated before prosecution did its job— but the reaction was fast and decisive. In many other cases, the pressure had to come from above and outside to get things moving. But we need people on the ground who can reach them, contact their lawyers, and verify facts. Without them it’s nearly impossible. Sadly, in our region, too many journalists avoid unity.

CU: The European Media Freedom Act (EMFA) is seen as a significant tool to protect journalists. Shouldn’t we expect the situation to improve? How can it be strengthened?

Flutura Kusari: Yes, the EMFA is probably the strongest legal instrument for media freedom Europe has had in a decade — maybe even globally. Governments can no longer claim ignorance. But Media companies also need to comply. One criticism often used against journalists — sometimes validly — is that we lack transparency in our own operations. But the most critical part of EMFA will be ensuring the independence of public broadcasters and regulatory bodies. Without that, the law loses its force.

CU: Denmark, tried to create a media ombudsman, but the results are disappointing.

Flutura Kusari: When I hear “ombudsperson,” I honestly shiver. Denmark introduced a risky model that, ironically, could be misinterpreted as compliant with EMFA. The problem is that when a country like Denmark — often seen as a model democracy — does something questionable, it sets a precedent. Other countries, including some like Greece, can say, “We’re just following Denmark’s example.” We’ve sent our concerns and legal analyses to the Danish government. We hope it reconsiders.

CU: So what form should independent regulation take? Governments want to control public broadcasters and the narrative, of course.

Flutura Kusari: They do, and it’s not only Hungary or Slovakia — it’s also Malta, even France to some extent. And in countries with a weak rule of law, every new tool can easily be turned against journalists. For that reason, we support self-regulation. If we strengthen self-regulatory and independent regulatory bodies, we can protect media freedom without creating instruments that could be abused. Institutions should be based on principles and processes, not individuals. Yet in practice, too many still depend on who’s in charge at a given moment. Strengthening the systems we already have is safer and more sustainable than inventing new ones that can be politically weaponised.

CU: But as we’ve seen in cases like the Predator spyware scandal, governments sometimes dismantle independent authorities altogether.

Flutura Kusari: Yes, absolutely. We’ve seen governments fire entire oversight bodies that were actually working well. Courts don’t function properly, and few believe justice will ever be served. It’s disheartening because we know the standards, we know what should be done — but we face politicians who simply don’t believe in media freedom any more. And beyond that, there’s a growing lack of respect for journalism as a profession. Politicians don’t have to like journalists, and journalists don’t have to like politicians — there should be mutual respect for the roles each plays in a democracy. That respect is eroding, not just in our region but globally, including among powerful countries that once set the example.

CU: It’s ironic, because this region was supposed to set the standards for others…

Flutura Kusari: That’s what makes the backsliding worrying.

Photo credits:

1,3,5 ©Sam Glazier, Courtesy of ECPMF

2,4 ©2025 Alex Grymanis, Christos Karagiorgakis / iMEdD