Television news is shrinking, older demographics are disengaging, and climate coverage is reaching fewer people across key markets — even as public interest remains strong. The result: growing information gaps in one of the most urgent policy areas of our time.

That’s one of the main takeaways from "Climate change and news audiences report 2025: Analysis of news use and attitudes in eight countries", based on a survey of more than 8,000 online news users across Brazil, France, Germany, India, Japan, Pakistan, the UK, and the US.

The study (now in its fourth year) was conducted by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford by Waqas Ejaz, Postdoctoral Research Fellow; Dr Mitali Mukherjee, Director of the Reuters Institute; and Dr Richard Fletcher, Director of Research.

According to the 2025 report, climate news and information use has fallen across several Global North countries over the past four years, while remaining comparatively stable in India and Pakistan, which were included in the survey.

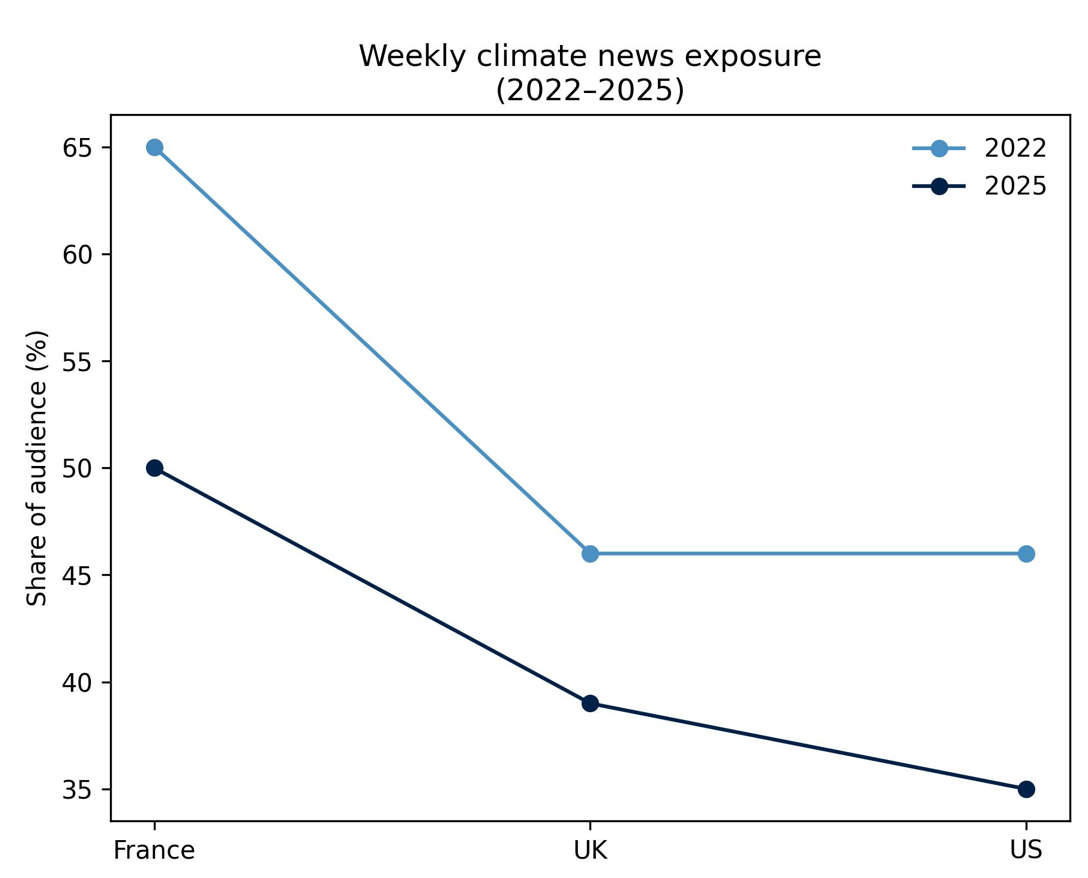

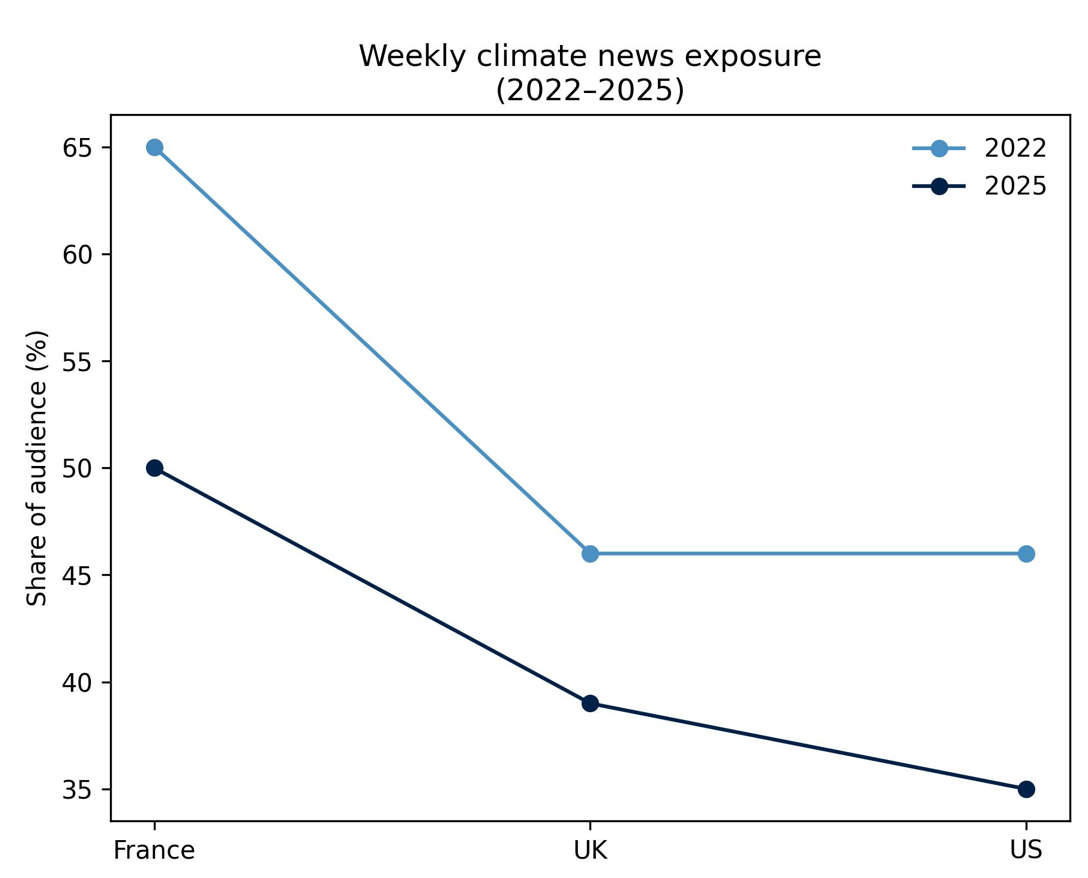

Across the eight countries surveyed only 47% of respondents said they had encountered climate-change news in the previous week, continuing a downward trend observed since 2022. Weekly exposure has declined steadily in France, Germany and the UK over this period, reflecting a broader pattern across high-income democracies rather than a short-term fluctuation. (click Image to enlarge)

"There are several factors for these trends," Waqas Ejaz, principal researcher for the Oxford Reuters Institute, explains. "One is that major global events, like the UN COP summits, haven’t generated major headlines lately.

There’s less momentum politically, which makes it harder for journalists to find compelling hooks. In parallel, we’re also seeing stagnation in climate policymaking in many countries. If political leaders aren’t advancing action—or are even pulling back—then there’s simply less “news” to report," he says.

The report identifies two overlapping dynamics behind the decline. First, access to climate news via television has decreased, reducing overall reach. Television remains a key route through which many older and less digitally engaged citizens encounter public-interest information. (click Image to enlarge)

Second, the decline is concentrated among older audiences. Across the eight surveyed countries, weekly exposure to climate news among people aged 55 and over has fallen by around 10 percentage points since 2022, from 72% to 62%.This group has traditionally relied more heavily on television news, making it particularly affected by reduced TV use for climate coverage.

Importantly, the report finds little evidence that declining exposure reflects falling interest in climate change itself. Audience interest remains broadly high, and the authors suggest the trend is more likely explained by a combination of shifts in media consumption (age, digital Media) with reduced supply of climate coverage, especially on TV. However, while online news platforms and social media continue to play a role, their reach has not fully compensated for the decline in television-based exposure. Climate news use among younger audiences and via non-television sources has remained comparatively stable, indicating that the overall decline is driven primarily by older cohorts.

"TV has been the single most important source of information for climate news for as long as we have been doing this study, but we can confidently say that overall TV consumption is going down," says Waqas Ejaz. "But TV is not the only thing that comes to my mind when I think about news anymore," he adds. “We had at least one in three people saying that they want video-based content when it comes to climate change” says Waqas and explains that this trend has implications for journalists. "If you want to reach people, especially younger or more mobile-first audiences, you need to think visually and digitally," he adds. This trend is also reflected in the 2025 Digital News Report, published by the Reuters Institute at the University of Oxford. (click Image to enlarge)

A new credibility gap

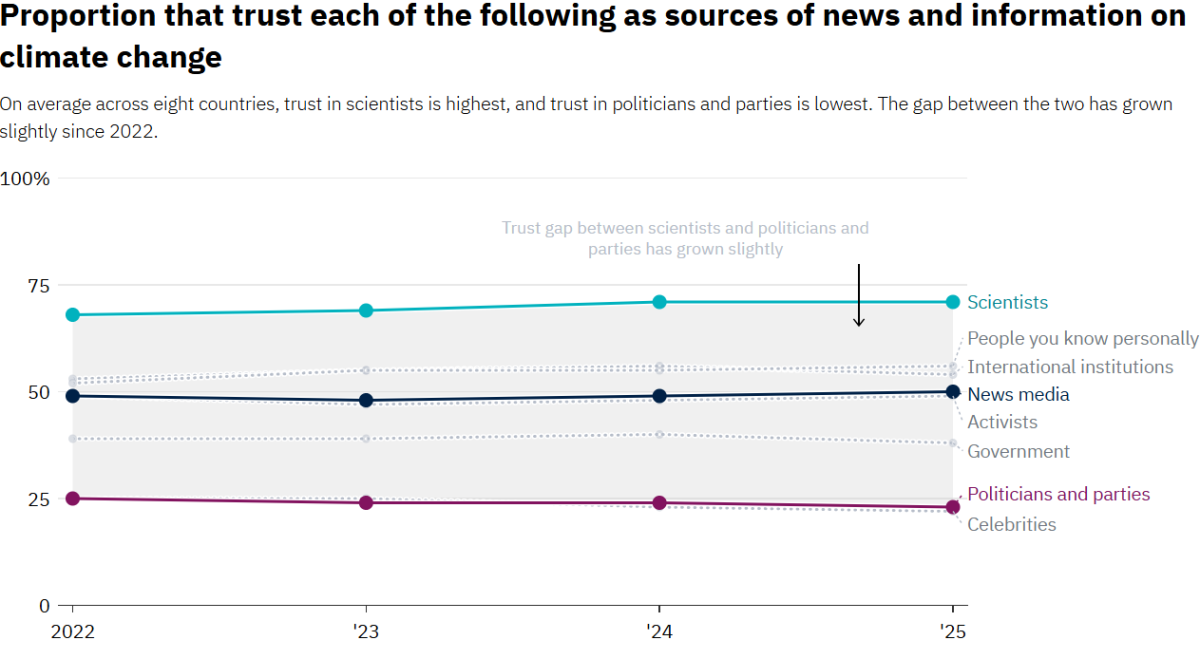

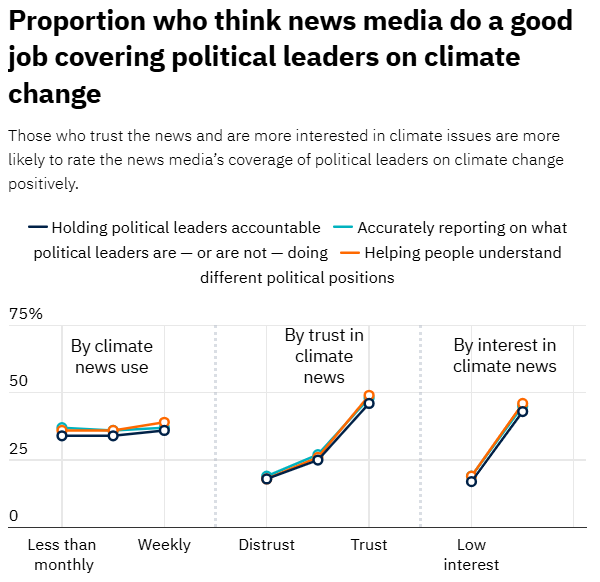

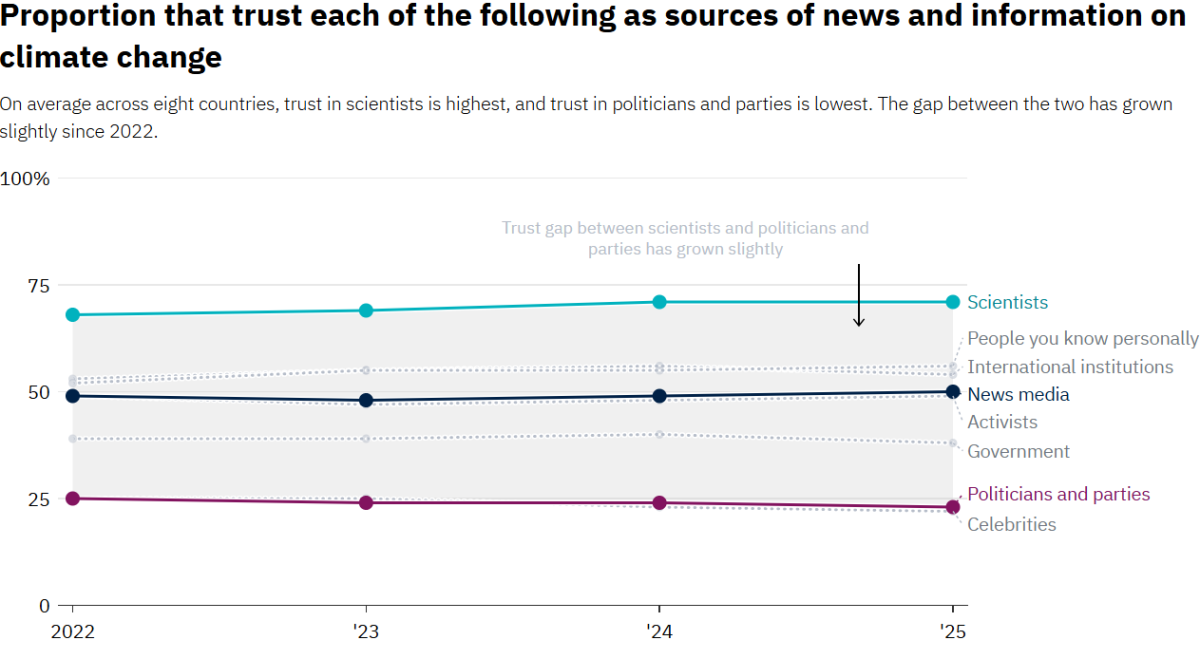

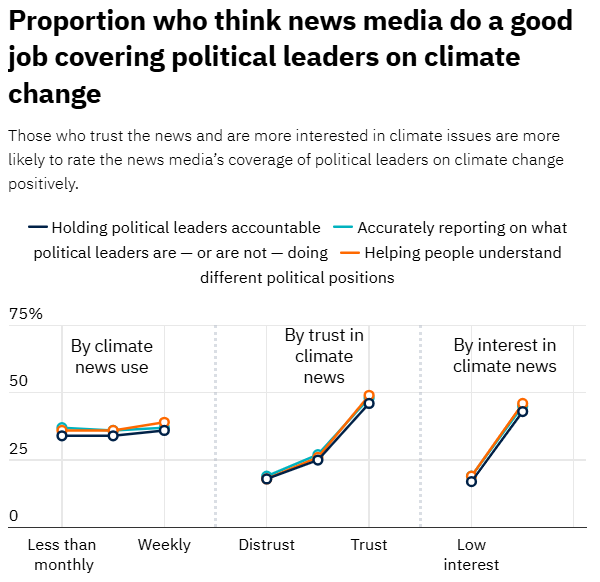

The findings also reveal a pronounced credibility gap. Trust in scientists as a source of climate information remains high across the surveyed countries and has even increased slightly since 2022, reaching an average of 71%. By contrast, confidence in political leaders on climate change is markedly lower: only around one in three respondents on average say they are confident that political leaders have the right priorities and are making the right decisions on climate policy. The report highlights substantial variation between countries, but the overall pattern is consistent.

"France tends to be more sceptical — both toward the media and toward political leaders. Germans are more aligned with global trends, but there’s a strong backlash there too, especially around climate protests and farming policies. In both countries, people expect a lot from their media — sometimes perhaps more than is realistic, given the resources available. But the underlying desire for better climate information is real," comments Waqas Ejaz. (click Image to enlarge)

But the overall agenda around climate change is being downgraded mainly by politicians. "We saw in 2022 the extreme drought in France and then we have extreme weather events and flooding in Hanover in Germany. Climate change is sort of being pushed back as a topic in European public discourse".

A paradoxical situation is met across the eight countries but it's even more bold in France, Germanyt and thew UK according to the survey: "On one hand, they (people in the West) want greater depth, more education, more information on these topics. But if their political representatives spend more money on media, that's not something that they are happy to go along with. Have you seen public funding in public broadcasters going up in these countries?" Wagas asks rhetoricaly. “The funding in climate related or any media funding is pretty much stagnant. And if it's not going down” he adds.

Naturaly the question then is what should journalists do in this environment-a question Wagas says he receives often. (click Image to enlarge)

His answer: "Your audience is still there. The issue isn’t going away. And when climate stories are told clearly, with integrity and usefulness, people respond. We need climate journalism now more than ever — not just for awareness, but for action."

Waqas Ejaz: "Misinformation about climate change is no longer the problem. Inaction is."

How should journalists navigate the paradox of declining climate coverage amid rising public concern? Drawing on four years of data, Waqas Ejaz explores why journalism is pulling back, how audiences engage with climate content, and what journalists can do to close the information gap.

How should journalists use these findings?

WE: The most important thing for them to do is to go back to basics and continue working on the stories they think are important in regards to climate change. Once we reach 2030, the opportunity will most likely have passed. So we need this final push. They’re already doing a good job. A high number of people across years and countries are extremely concerned about this issue. I think the second point is that, although this isn't specifically mentioned in this year's report, it's important to make people aware of the seriousness of the situation. I think it is okay to make people a bit more scared. They need to know that we are in a very bad state.

What’s the role of misinformation in all this?

WE: I’m happy to report two things. Firstly, the percentage of people who are misinformed or deny the facts is around 10 to 15 per cent of our overall sample. This percentage has remained consistent over time. So, over the past four years and across these countries, that percentage has remained roughly the same. This is a good thing, as we have those sceptics in a significant minority. Secondly, I would like to emphasise that, while this is not currently a mainstream issue, I personally believe that misinformation about climate change is not a significant problem. It's not that significant a problem. The problem in climate discourse and public climate discourse right now is inaction.

Can you share any positive examples — stories or outlets — that are doing this well?

WE: In the UK, we have Carbon Brief, which is a news outlet that focuses entirely on climate-related issues. It’s a philanthropic organisation which I know well. They usually produce long-form journalism, and they’ve made a name for themselves with their rigorous, data-rich, complicated breakdowns of different stories. That’s one example. The Guardian also has pretty good climate reporting. In the Global South, I'm afraid we don't have many positive examples. Mostly, it's influencers, creators, and individual journalists who are working on that, but they're working on a lot of other things too.

What kind of stories resonate most with audiences?

WE: Practical, explanatory stories. People want to understand what’s happening, and they want to know what they can do. One example came from an editor in Denmark, who published a detailed piece on how to build a sustainable house — sourcing materials, finding local vendors, all of that. It performed extremely well. What didn’t perform as well was more abstract coverage. People are looking for tangible advice — not just moral appeals or slogans. They want to be equipped, not just informed.