Anna-Louise Milne, University of London Institute in Paris

When sharp, abrasive arts of differing forms come together, what happens? The rub might make them ring out, possibly grate, or sharpen even more. All of this is happening in the dense, fascinating show that the writer Lou Stoppard has put together with the Nobel-prize winning author Annie Ernaux at Paris’s Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP).

Stoppard was writer in residence at the MEP in 2022 and the exhibition Exteriors: Annie Ernaux & Photography is the culmination of that time. The show takes pages from Ernaux’s slim book Journal Du Dehors (1993) and sets them alongside photographs from the MEP’s collection, suggesting possible threads, resonances and affinities.

Ernaux’s Journal Du Dehors was translated by Tanya Leslie as Exteriors and published by Fitzcarraldo in 2021. The text takes the form of random journal entries spanning seven years from the 1980s and early 1990s. It concentrates on fleeting encounters made while Ernaux was travelling regularly into the city from her home on the outskirts of Paris.

The addition of the images and the separation of the pages in the exhibition intensifies Ernaux’s writing, creating plenty for visitors to pore over. But the images also add space in how Ernaux’s writing can be interpreted. The routine of the daily commute, the unchanging underground corridors with their familiar beggars, the same parking lot outside the same supermarket – these are the patterns of the way we live to work, which give Ernaux’s Journal its particular corrosiveness.

Ernaux’s work gains an added brilliance and stillness when it is read from panels on the wall. The paradoxical qualities of her writing in Exteriors, the sense of the timeless tragedy and also the ephemeral nature of the scenes captured become more vivid against the pictures. That moment, that dress, those words, those socks exist in that time and place, but because they have been captured they also exist forever.

Cutting imagery

Ernaux has long wanted her writing to work like a knife. Her style is short, sparse, unlyrical. She cuts to the heart of the things she is writing about, every word necessary. And the poised, thoughtful curation of this show is an extension of her skill in making the cut. It shows us that everything is in the detail if it is seized sharply enough to reveal its significance. Many of the photographs displayed alongside her words are dazzling in this respect.

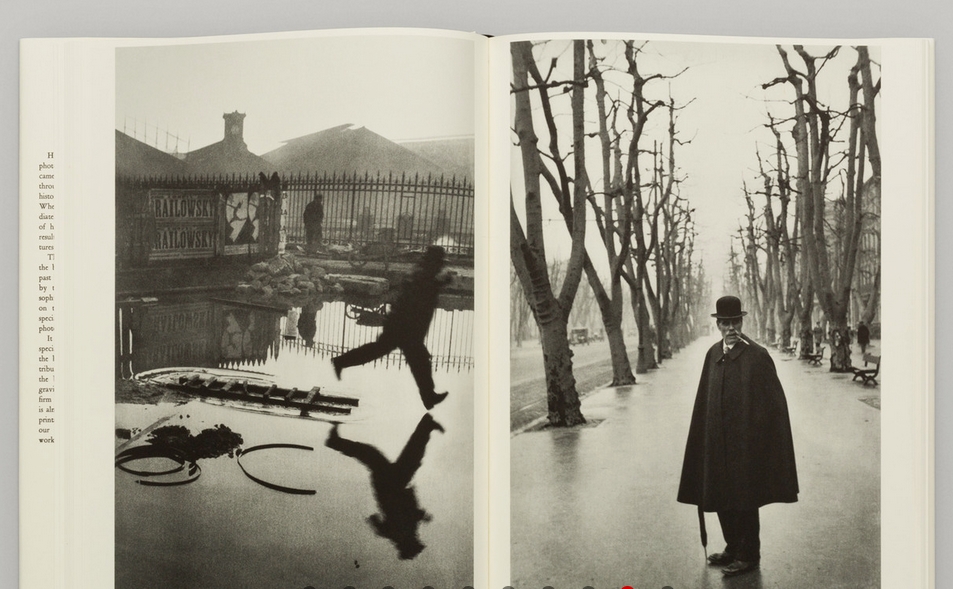

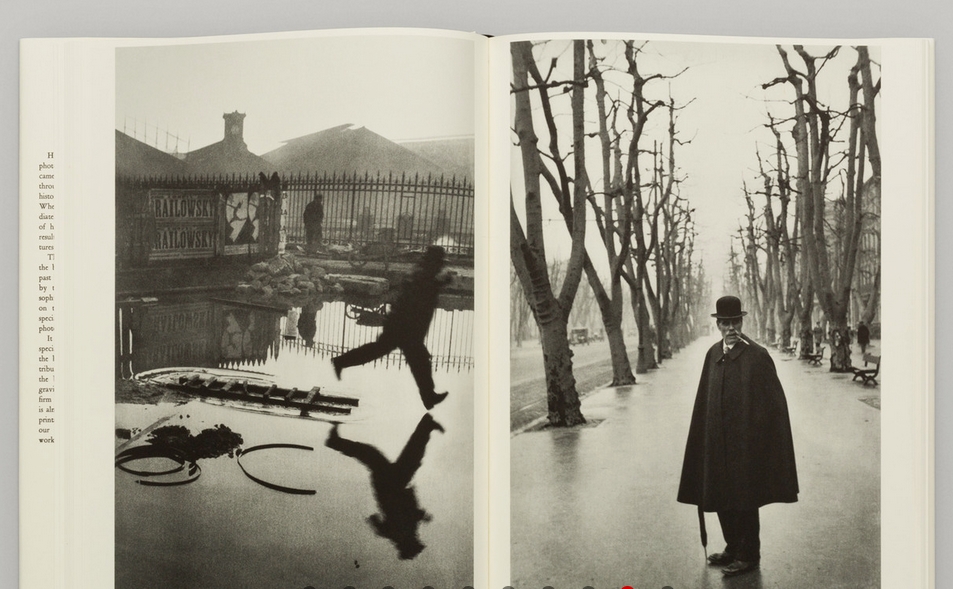

They are almost overwhelmingly characterised by what the French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson called “images à la sauvette” – scenes glimpsed and grasped from the street, capturing people without their knowledge, seizing their singular presence in that moment. One particularly successful pairing demonstrates how this approach can generate wonderfully different images.

ヒロ若林-康宏-HIRO-WAKABAYASHI-Yasuhiro-Shinjuku-Station-Tokyo-Japan-1962-Seven-gelatine-silver-prints-mounted-to-board-120-×-76.8-cm-Edition-from-6-3-APs-@-PACE-MACGILL-Art-Basel-2019-1024x607

On one side of the narrow, corridor-like gallery are a succession of small, distinct images by American photographer Harry Callahan, taken from his French Archives series of the 1950s. These almost black prints are shot through with strips of sunlight or just minimally dappled. Figures appear enigmatically etched against the spare light, crossing in and out of visibility.

On the other wall there is a fabulous montage by Japanese-American photographer Hiro. These images are life-size, holding the cramped commuters of a 1960s Tokyo train in unwanted exposure through the carriage windows, their gazes and fingers pressed against the glass, reaching out to us. On one side of the gallery, then, there a deep sense of solitude. On the other, the press of people in on us.

Together these photographers illuminate the strange quality of this phase of Ernaux’s work, which was unremittingly close to ordinary life and yet detached. She is always a detached onlooker, even when she imagines that these things are so ordinary that she might as well be looking at herself.

A detached onlooker

The inclusion of several series of works by Japanese photographers is striking because it creates a sense of estrangement in contrast to the way Ernaux has systematically embraced the familiarity of ordinary French life. The same effect is produced by the photographs from more recent Parisian times, particularly in the room with two large works by Mohamed Bourouissa and one by Marguerite Bornhauser, the only piece in the show that doesn’t depict people.

The two prints by Bourouissa show scenes of black life in France. One depicts a group of four youths standing around a burnt out car in a dirty alleyway. One of them stands on the roof, his upper torso and head cut off by the framing.

The-Decisive-Moment—originally-called-Images-à-la-Sauvette—Henri-Cartier-Bresson-Photography-Book

The other photo shows a man being arrested. He is handcuffed, almost naked, staring blankly up at a woman, who might be his girlfriend. She is barelegged, wearing just a long t-shirt. The policeman and the woman are also decapitated by Bourouissa’s framing.

Meanwhile, Bornhauser’s piece shows the impact of a bullet on glass somewhere near the Paris attacks in 2015 after the terrorist attacks.

These are scenes of modern violence and social decline. They show that even the minimal social and physical mobility of Ernaux’s generation has run aground. They also bring into focus the violence in Ernaux’s work, particularly in the pages alongside Bourouissa’s images. These pages are less documentations of what she saw but extrapolations of what could be. They speak of fear, of empty spaces where violence (even rape) could go unheard, and of the cruelties of parental ambition that creates unhappy adolescence.

All in all, the viewer comes away with a sense of the extraordinary power of these images of everyday life. And for those who already harbour an admiration for Ernaux, Exteriors is an opportunity to see more clearly how she sharpened her eye and her ear against the routine of her daily commute.

Anna-Louise Milne, Director of Graduate Studies and Research, University of London Institute in Paris

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.