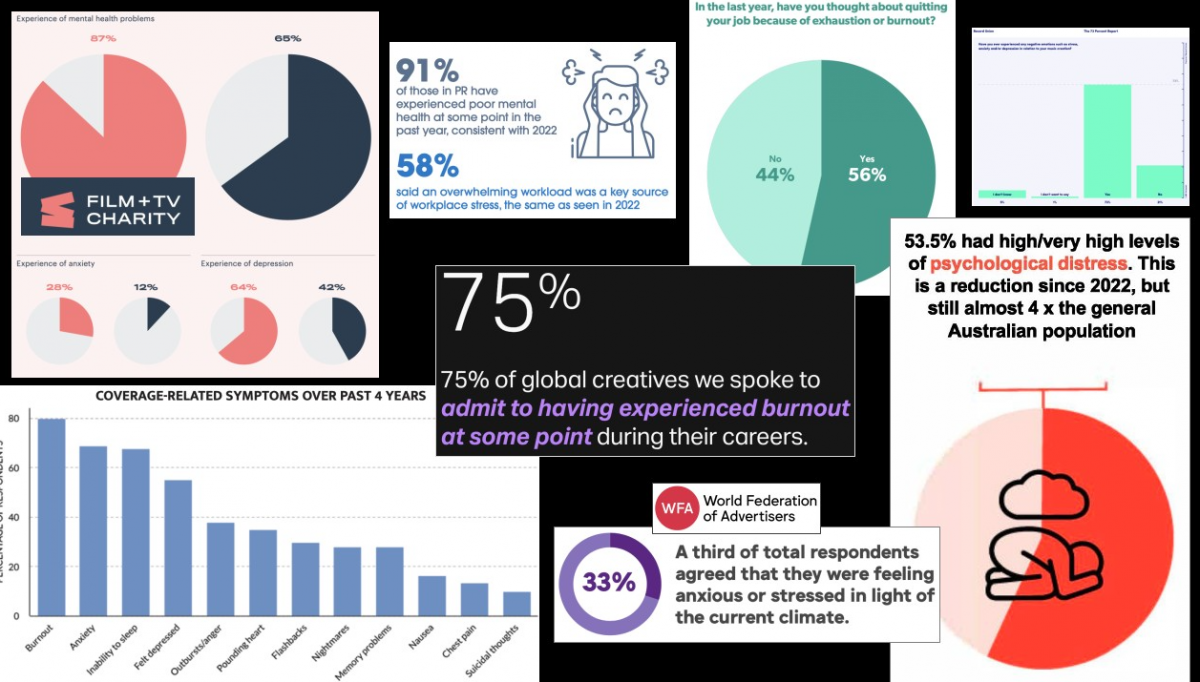

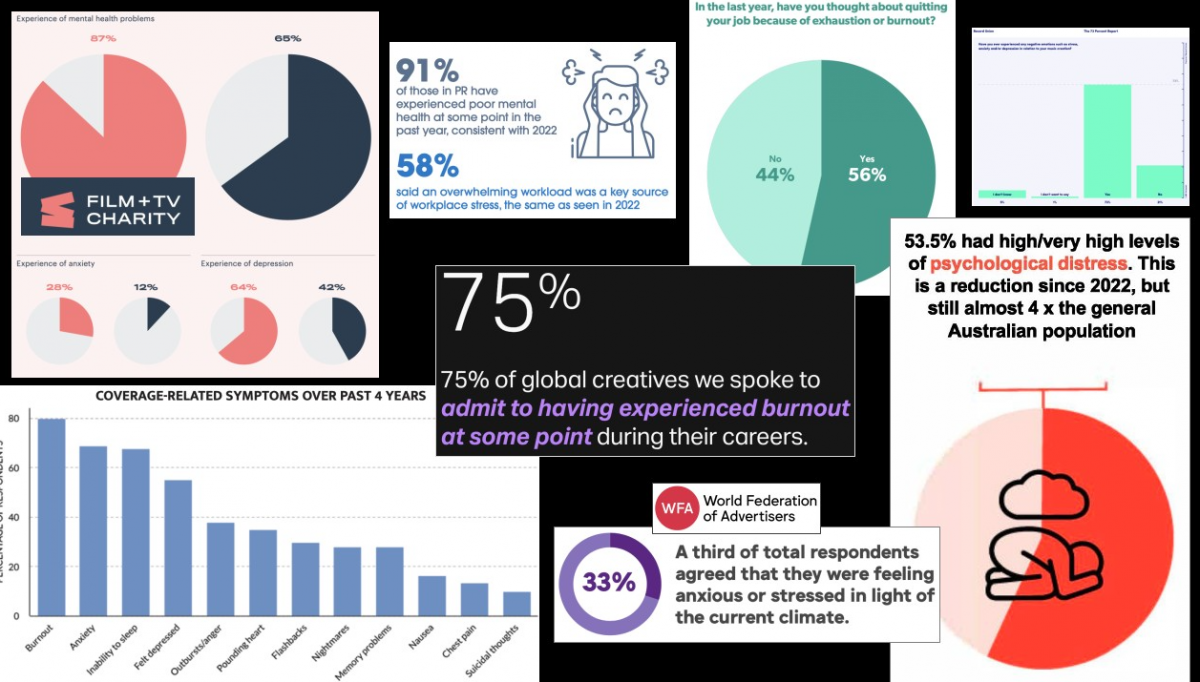

Media scholar of the University of Amsterdam, Mark Deuze reveals that mental health struggles in creative industries are widespread to an exhausting degree. However, they aren't new, but rather they're deeply rooted in historical patterns. While workers across journalism, arts, and media face anxiety and burnout, they remain passionately committed to their work. This "cruel optimism" paradox drives both their suffering and resistance to exploitation.

Mark Deuze's new book, Well-Being and Creative Careers, due out this summer, examines how industry-wide issues in journalism, advertising, film, games and content creation are leading to anxiety, burnout and depression, despite workers' passion for their craft. Profesor Deuze spoke to Creatives Unite about these issues:

Q: Your research confirms what we empirically believe already: we’re in trouble. Oddly, we seem almost happy about it—a masochistic pleasure that’s consistent across cultures and professions. For example, although high rates of heart attacks and strokes have long been known in journalism, the mental health crisis was rarely discussed. Is this tied to structural changes in the industry over the last 10–20 years, or has it always been there, just unaddressed?

A: This has always been happening. Frank Fedler, an American colleague, studied 19th-century journalists and found the same patterns: a semi-militaristic work style, sensitivity to hierarchy, overworking to please editors, and an inability to speak up. There is also a fascinating book by an anthropologist who, by chance, ended up in Hollywood in the late 1940s. Hortense Powdermaker’s In the Dream Factory, mirrors today’s realities. People, despite struggling, felt compelled to project constant happiness—a forced extroversion eerily similar to today’s culture.

This isn’t new. A recent book, There’s No Crying in Newsrooms, explores how these issues persist, especially for women. Historically, two insights stand out:

If someone in journalism, the arts, or media acts surprised by these problems, they’re likely in charge or in a rare, well-managed pocket. These issues aren’t tied to job types or employment structures. While freelancing is more common today, the problems aren’t worse now—they were similarly bad in the past. Fair pay matters, but a permanent contract doesn’t guarantee well-being.

Q: Your research spans psychology, sociology, and the political economy of media, showing how deeply these issues are connected. This makes me think about Me Too, which started out in the creative industries but became a global movement. Why did it emerge as the breaking point? Does it reveal something unique about our moment?

A: Me Too, alongside the global austerity crisis, Black Lives Matter, and the pandemic, acted as accelerators, shifting localized issues into global discussions. A new generation of workers is also more vocal about their experiences, partly because of their growing up on social media, where outrage and emotions are amplified. Younger people are more explicit about what feels right or wrong, raising awareness.

These industries were hit hardest during austerity and the pandemic, shutting down first and reopening last. Collective organizations have surged, not just through unions but also informal collectives and online groups. In the Netherlands alone, there are 100+ creative collectives giving workers a voice.

Another shift is how people view work. For decades, especially in the West, work has been central to identity. But COVID-19 has shattered that fantasy. People realized what truly mattered: friends, family, freedom, and simple joys. Now, workers in creative industries are refusing to return to the office full-time, signaling a profound shift in priorities.

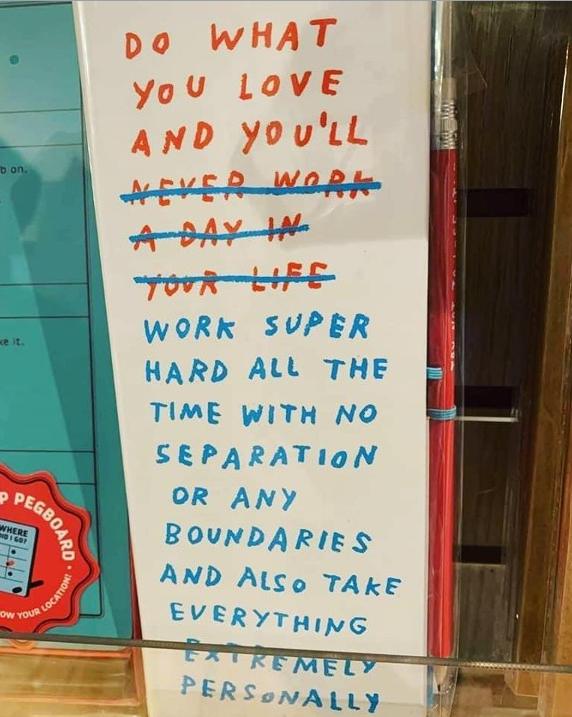

Q: Let’s focus on the psychological dimension. You’ve described how work becomes central to identity, yet it also makes people sick. Journalists often say their work doesn’t align with their ideals, yet they keep doing so. Musicians endure stress and burnout to make others happy. What psychological processes contribute to this ambiguity?

A: People enter creative industries with romantic ideals—journalists see themselves as pillars of democracy, artists believe their work is essential to society. But reality rarely matches these ideals. Over time, professionals adopt a craft mentality, believing hard work and dedication lead to creative autonomy. Instead, they face gradual disenchantment.

I’ve presented this work to industry professionals, and the responses are striking. On the one hand, people respond with disbelief: surely, things are not this bad? On the other hand, many describe their careers as if they’re in recovery, confessing that their passion cost them marriages or health. This mindset is destructive. The industry itself doesn’t change; it remains indifferent. Explaining this to aspiring students is difficult, but it’s a reality everyone in these industries eventually faces.

Q: In your book, you talk about cruel optimism. Workers are burned but remain optimistic. Can you elaborate?

A: Cruel optimism, a concept by Lauren Berlant, explores why people keep doing things they know are harmful. In creative industries, this manifests as a defiant act against capitalism. Artists aren’t naive—they’re often highly critical of their industry. But they continue as an act of resistance and self-expression.

Traditionally, sociologists saw this as creatives’ Achilles’ heel: over-identifying with their work and becoming blind to exploitation. Instead, I argue this passion can be a strength. It drives people to collectively organize, support each other, and create alternatives.

Q: There are successful independent initiatives, especially in journalism in the Netherlands. Can you elaborate?

A: Not specifically in The Netherlands! In my earlier book, Beyond Journalism, Tamara Witschge and I documented instances of journalists setting up their own independent companies around the world. Many journalists felt traditional newsrooms no longer offered the support they needed, so they turned to entrepreneurship. While precarious, it provided both solidarity and strength. This reflects cruel optimism: they knew the risks but gained a sense of community. Today, this optimism is more about resisting a system that would kill their craft, creativity, and art.

Q: What can be done? You mentioned three key factors: lack of reciprocity, low organizational justice, and unusually high job demands. What solutions do you propose?

A: Solutions must happen on multiple levels. Individually, resilience and self-care are important but insufficient. Organizations need transparent policies on funding, promotions, and fair pay, along with clear codes of conduct and work-life balance. Leadership training is crucial—many leaders in creative fields lack management skills.

Industry-wide action is also needed. The book normalizes discussions about mental health and debunk myths like meritocracy. Real change requires individual, organizational, and industry-wide efforts.

Q: The EU treats creative industries as a unified sector. Is the mental health crisis part of a broader societal crisis, or do we need a separate debate for journalists?

A: I group diverse professions because their data tells a similar story, highlighting the potential for new alliances. While each field feels unique, mental health challenges are the same. Collective action is stronger: the bigger the group, the louder the voice.

Decision-makers often only care about numbers, not people. Workers give all but are treated as cogs in a machine. Mental health is now a global conversation, with the OECD estimating it costs 7% of global GDP. Beyond economics, art, and media are where we still connect in a polarized world. If these professionals unite, they can make a powerful case for change.

Q: Are there differences among national industries?

A: The key difference is how mental health is discussed across cultures. The Anglosphere—Australia, the UK, Canada, and the US—leads the conversation, while other regions often keep it shrouded in stigma. Resources vary dramatically worldwide.In Australia, employers face serious consequences for neglecting employee health and social safety, while in places like Nigeria, such discussions might be taboo.

Differences often exist within companies more than between countries. For example, 80% of employees in a film production company might feel supported, whereas 20% experience it as toxic. Mental health support requires creating a safe environment for discussion and understanding individual needs.

Globally, the challenges impact young people, minorities, those with disabilities, and people with caring responsibilities most intensely. The industry was designed primarily for a very particular type of person and thereby excluding most, highlighting its structural limitations. Mental health support isn’t just a policy—it’s a practice of genuine care and understanding.

Image: Wikipedia