The diplomatic crisis between the two governments and allied countries was unexpected: Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis was due to meet with British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak in London a couple of days ago, but the meeting was cancelled at the last minute by No 10. The cancellation came after Mr. Mitsotakis stated that the Acropolis marbles held in the British Museum for 200 years, should be returned to Greece, comparing the situation to cutting the Mona Lisa in half.

The cancellation of the meeting has triggered a diplomatic spat and prolonged a centuries-long feud over the sculptures. Mitsotakis criticized Sunak's decision as "wrong and undignified" and expressed annoyance at the cancellation. UK government sources said discussing the marbles was "impossible" after Mitsotakis' comments and the UK position is they will remain in Britain.

Greece asserts that the marbles, taken from the Parthenon temple by British diplomat Lord Elgin in the early 19th century, were stolen, while Britain maintains it acquired the sculptures legally through a legal document of the Ottoman Empire. The validity of the claim has never been questioned let alone investigated and some researchers assert that Lord Elgin, either way, took more than he would be entitled to by this questionable legal document. The original firman was lost and an Italian copy is too vague to clarify the deal.

Greece first requested the marbles' return in the 1830s but the British Museum refused and the dispute has continued for 190 years since then. The British government's position is that the Elgin Marbles are part of the permanent collection of the British Museum for 200 years and belong there, and it is reckless for any British politician to suggest that this is subject to negotiation. The arguments for and against the return of the Elgin Marbles to Greece are complex and multifaceted.

The main argument against returning the marbles is that Lord Elgin's legal removal saved them from destruction, and made them available to a wider public than they would be in Athens. The British Museum also argues that the marbles are part of the permanent collection and belong there. Returning the marbles to Greece would set a precedent that would empty many great museums of their collections.

The depletion of museum collections would lead to the potential deprivation of access to iconic objects that belong to humankind, rather than individual nations, the argument goes. Source countries do not always have adequate facilities or personnel to receive repatriated materials and objects are safer where they are now, the argument goes.

The importance of context in cultural objects

But it is one that does not apply to Greece. The country has implemented the conditions set by the British government, most notably the restoration of the Acropolis and the building of a new museum to house the marbles if returned. The main argument for returning the marbles is that their removal from Greece was illegal, and they should be returned to their rightful owners, and UNESCO resolutions support their restitution to Greece. The Parthenon marbles are the most paradigmatic case, but the debate about how museums should handle colonial-era artefacts spans way beyond Greece and the Lord Elgin case.

UNESCO has envisioned decolonization as repairing modernity's traumas through cultural heritage, which can be a tool for that end. The debate around the return of artefacts to their countries of origin involves several main schools of thought. One perspective advocates for the repatriation of cultural artefacts, emphasizing the ethical implications of colonial-era acquisitions and the importance of restoring dignity and historical continuity to the communities these artefacts represent.

There is a growing awareness of the ethical implications of these acquisitions, which has sparked a global repatriation movement, which is not only about returning important objects but also about restoring cultural identity and historical continuity to the communities these artefacts represent. It echoes the significance placed in decolonization contexts on understanding indigenous frameworks for considering heritage value.

Elgin removed the objects from their original context and meaning. Returning them would restore Greece's cultural patrimony. The removal was an act of appropriation and despoilment, the argument goes, so Greece has a sovereign right to reclaim its cultural property.

Mobility and 3d printing

A 2022 report, revealed that secret negotiations between the Greek government and the British Museum examined options that could see symbolic or material compromise, such as rotating exhibitions through loans or high-quality replicas. Any accord would likely be nuanced, taking years to negotiate and requiring good faith on all sides. Loans, proposed by the Greek PM, go against UNESCO resolutions. Both the Greek Archaeological community and the British side reject the idea on legal grounds. In short, possession creates a de-facto legal right, while the Greek side questions the validity of "renting" something one owns.

Public sentiment in the UK appears to be shifting, with certain trustees now open to a less rigid line. The solutions that have been offered to bypass the dead end, transcend the function and scope of the museum from its current static form to a knowledge hub, while preserving its international role. 3D printers are currently reproducing several Parthenon carvings in the original Pentelic marble at the Institute of Digital Archaeology, and the copies are said to be indistinguishable from the originals.

This could allow the marbles to be experienced in London through the replicas, while the originals are returned to Athens. It would meet the BM's demand to see the marbles displayed among other civilizations while allowing the originals to be reunited. The British Museum rejected the request in 2022 without providing any explanation.

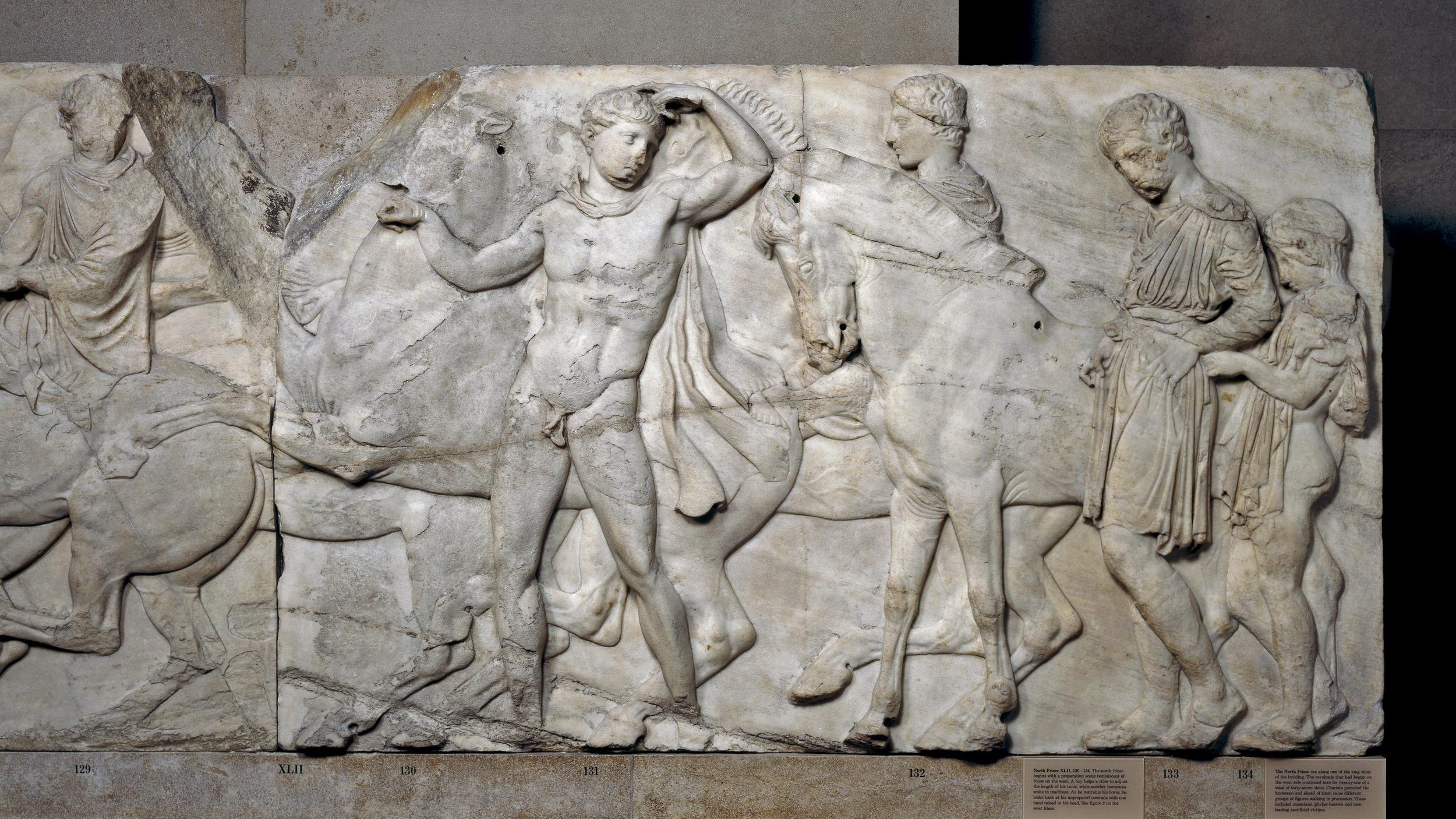

--Photo Credit: Marble relief (Block XLVII) from the North frieze of the Parthenon. Athens, 438–432 BC © Trustees of the British Museum--