By Étienne Balibar, Justine Lacroix, Dominique Méda, Thomas Piketty, Katharina Pistor, Guillaume Sacriste, Antoine Vauchez and Jonathan White – This is a reproduction. The article was first published at Le Monde

We have entered a new era. Of course, it is difficult to foresee what the emerging world will look like. But some trends are unmistakable. The abduction of Nicolás Maduro and Donald Trump's desire to seize Venezuela's oil resources, as well as the threat over Greenland, are not isolated incidents. They are part of a series of actions and declarations that seem to signal a lasting and profound evolution in our global system.

We are likely entering a new age of imperial conquests and what economist Arnaud Orain has called "finitude capitalism"—marked by growing rivalry between major powers for the control of resources (financial, natural, labour and more). But for how long?

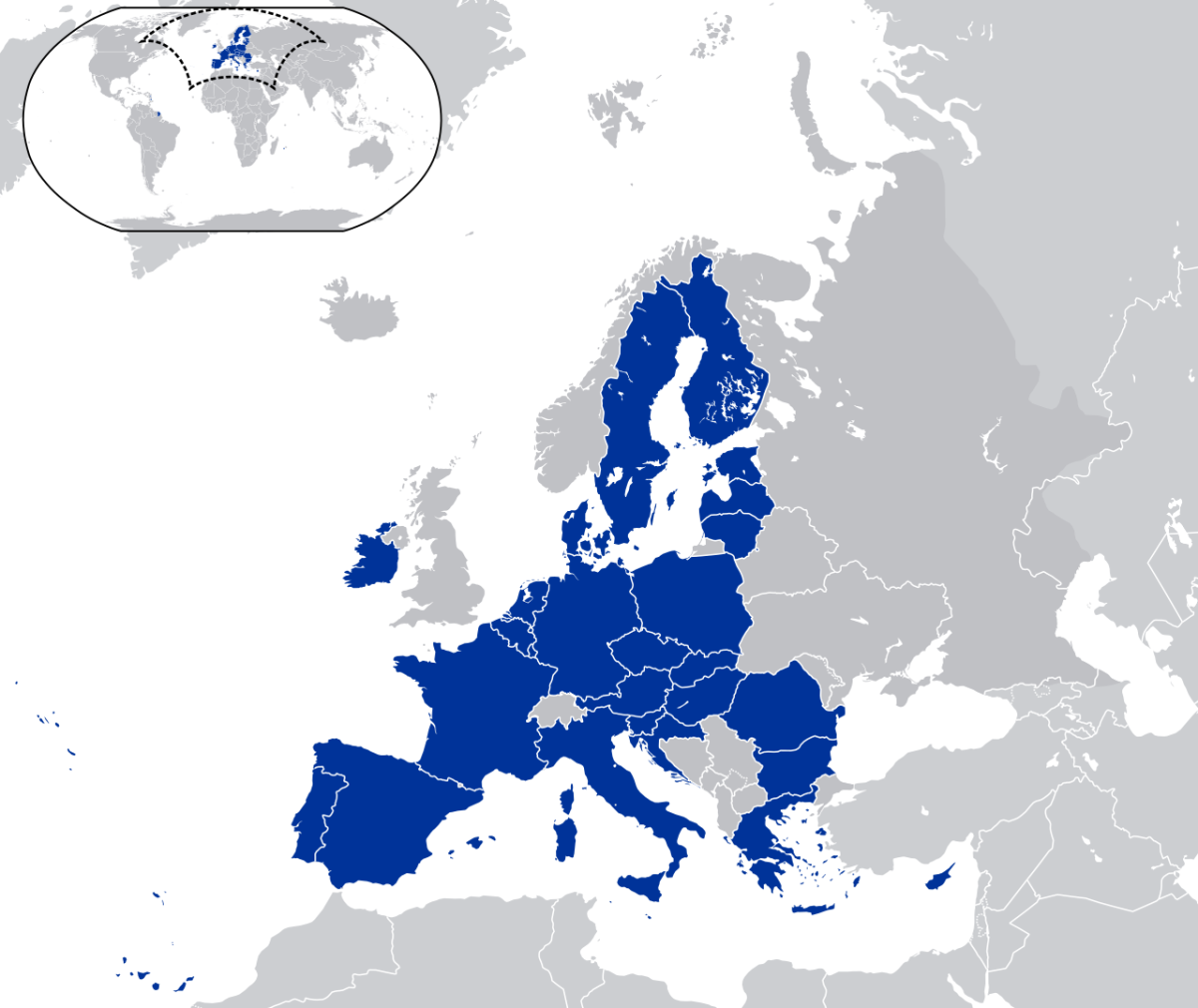

What we know about this world we have glimpsed is that gentle commerce and international law are no longer relevant. This new regime of capitalism is instead defined by the seizure of resources and the capture of value in the name of national interest and the law of the strongest. It sacrifices "weak zones", both political and economic, relegating them to the status of vassals or colonies on the peripheries of imperial centres. In this emerging world, the European Union is the lamb among wolves.

The American umbrella

The United States's shift toward alignment with autocratic Russian and Chinese powers has revealed the truth: "The European king had no clothes." What is more, the EU seems largely paralysed. Paradoxically, it lacks the flexibility that comes from the long histories of empires. While it appeared to react during the recent pandemic and financial crises, it did so without altering the fundamentals forged during the era of "liberal capitalism", which we know to have established in law a form of public powerlessness.

Overall, the EU was built over time on a "liberal-federal" logic: a liberal single market, free and undistorted competition, free movement of capital, an independent European Central Bank, free trade agreements, a very modest budget, and an abandonment of industry and sovereignty in the name of the American umbrella. The global shift we are witnessing renders this entire liberal-federalist apparatus obsolete.

In this context, the question is simple: is Europe capable of adapting to this new era? The issue is not to save the "liberal-federalist" institutions of Brussels, for this is not one of the adaptation crises that have marked the EU's history.

The challenge runs deeper. It is continental and civilisational in scale, and it concerns not just the EU but Europe and European societies as a whole. It affects their political freedom – in other words, their ability to collectively determine their own destiny, and thus their very existence as democracies. In contrast, autocracies, relying on the force of their public authorities, seem able to marshal their societies and economies to serve their predatory national interests.

Increased protection

The "new federalism" we call for must therefore move beyond the "liberal-federalist" stage to envision the association of European democracies as a "central bank" of democracy, ensuring for all European societies the concrete conditions required for democratic life, both against empires and against nationalist forces that act as their auxiliaries within member states.

To play this role as the ultimate guarantor of democracy, the new "social-federal" logic must, as [former MEP] Altiero Spinelli [1907-1986] advocated, establish a genuine European public authority capable of providing increased protection and sovereignty in support of national democracies – rather than preventing them from protecting themselves.

This new social federalism largely remains to be invented – not as supranational institutional engineering, but as the response of democratic states to the challenge of empires and as the condition for international relations, especially with the Global South, that move beyond the patterns of domination inherited from the past.

This new social-federal spirit must become the lever for a renewed mobilisation of European societies, for it is indeed their weakness that allows autocratic regimes – such as Viktor Orban's Hungary – to lock their people into nationalism and draw them into Faustian pacts with empires.

Poor capacity to respond

This "new social federalism" must therefore reconnect with the postwar resolve that, at the Hague Congress [in 1948], brought together a broad spectrum of political, labour, business, and civil society movements to revive the idea of European federalism. All evidence suggests that Europeans can now rely only on themselves, as their political, economic, and other leaders have shown since Trump's arrival the weakness of their ability to react.

The recent call by historic organisations of the European federalist movement for the establishment of parliamentary assemblies—bringing together national and European representatives to deliberate and implement the transformations needed for Europe's new path—could serve as a first step. These assemblies must be convened as soon as possible, for urgency is needed in the face of empires.

But to reach a goal as ambitious as the great postwar federalist congresses, a new transnational social alliance must be built: one that is rooted in the common interest of our democracies' survival and brings together all forces supportive of such a project, now fragmented both within Europe and within individual states. Only such a project, and its preparation around a new Hague Congress—modelled on the one that launched the first wave of European unification in 1948—will be able to guide and inspire the countless mobilisations needed to finally build the European party.

Signatories: Etienne Balibar, philosopher; Justine Lacroix, political scientist; Dominique Méda, sociologist; Thomas Piketty, economist; Katharina Pistor, legal scholar; Guillaume Sacriste, political scientist; Antoine Vauchez, political scientist; Jonathan White, sociologist.