The European Commission has published a new code of practice on the EU's AI Act, which came into force on 1 August 2024. The guidelines aim to clarify the obligations for companies developing and deploying “general-purpose AI models,” particularly those that could pose a “systemic risk” to the Union. They are also designed to help them understand whether their AI model falls under the new rules.

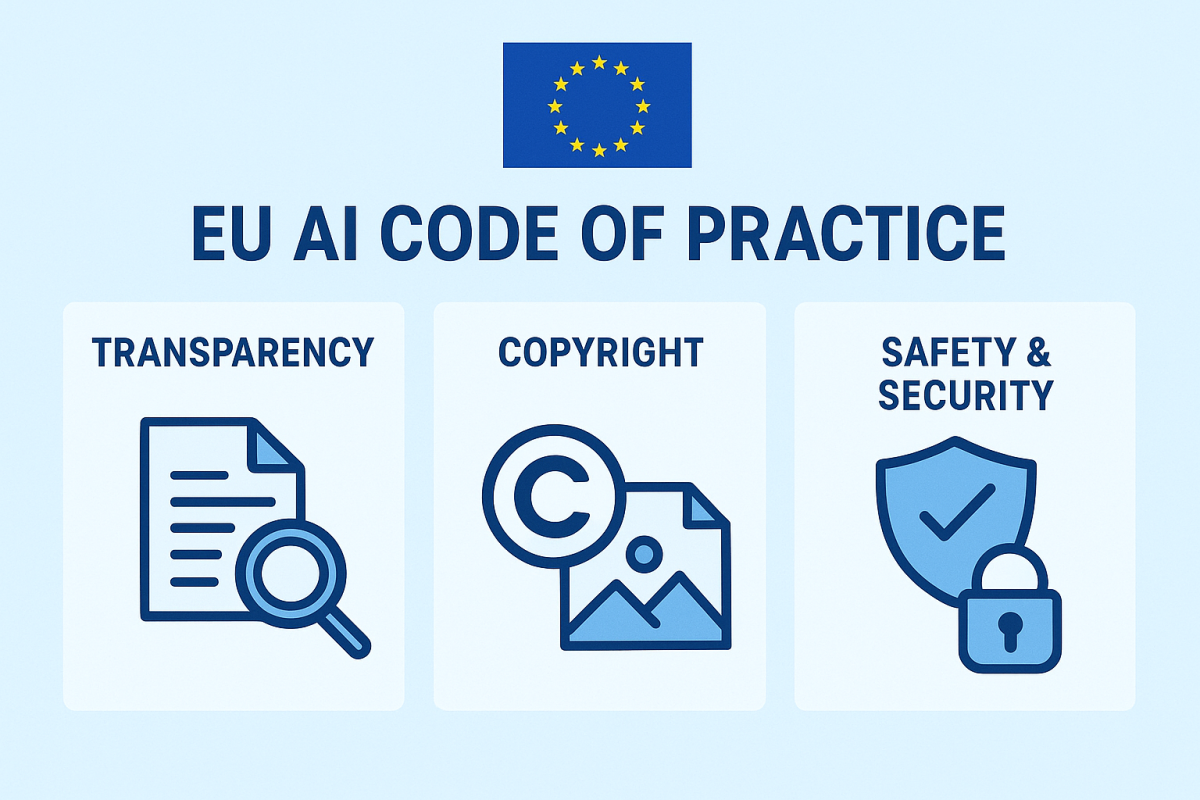

Structured around three core themes—Transparency, Copyright, and Safety & Security—the Code is intended to help companies demonstrate early compliance with Articles 53 and 55 of the Act.

Transparency

All GPAI providers are encouraged to improve openness by:

Documenting the design, capabilities, and limitations of their models.

Clearly stating both intended and reasonably foreseeable uses.

Informing users about how the AI functions, including any associated risks or limitations.

Copyright

To protect intellectual property, providers must:

Ensure training and deployment data complies with copyright laws.

Confirm that all copyrighted material has been lawfully sourced and used.

Safety & Security

For GPAI systems deemed to pose systemic risks, the Code recommends additional safeguards:

Establishing a robust risk management framework.

Performing regular assessments of safety and security threats.

Maintaining safety documentation and incident reports.

Designating internal responsibility for risk oversight.

Promptly reporting serious incidents to authorities.

While the Code is not legally binding, it is expected to serve as a key reference ahead of the EU’s mandatory compliance deadline in 2027. Officials say it offers legal clarity while easing the administrative burden for AI developers preparing for stricter enforcement in the years ahead. Importantly, following the Code does not guarantee full legal compliance with the AI Act.

What is a general-purpose AI model?

A key part of this is an indicative criterion that uses computational power to define a “general-purpose AI model.” An AI model is presumed to be a general-purpose AI model if its training computer is greater than 10 to 23 floating-point operations (FLOP), and it can generate language, text-to-image, or text-to-video content. This threshold is designed to capture models with approximately a billion parameters or more, which are trained on vast amounts of data. The document provides several examples to illustrate this, including models for language, image upscaling, and chess-playing, to clarify what is and is not in scope.

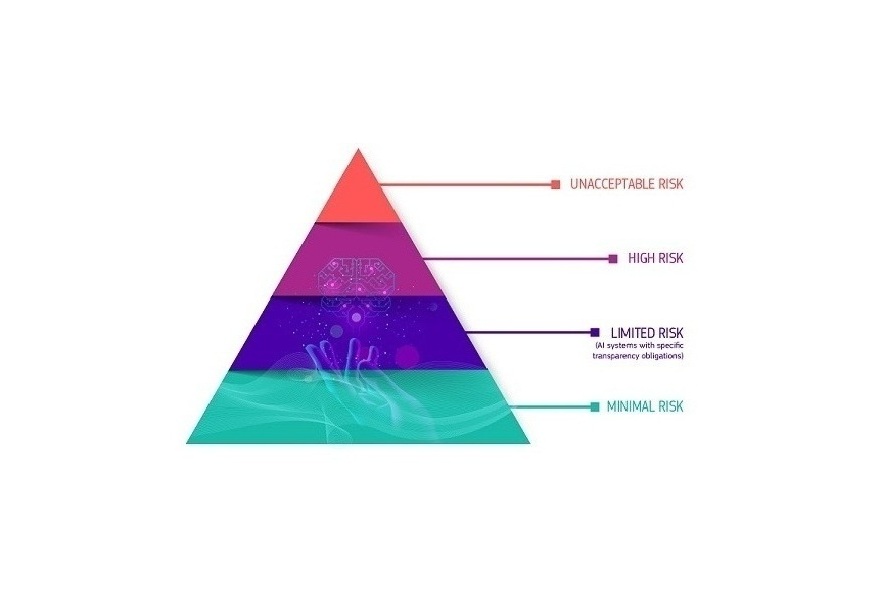

The guidelines also address more advanced AI models that could present “systemic risks.” These are defined as models with a significant impact on the EU market. A model is presumed to have systemic risk if it is trained with more than 10 to 25 FLOP. Providers of such models must comply with additional, stricter obligations, including conducting model evaluations, reporting serious incidents, and ensuring robust cybersecurity.

For developers, the guidelines offer important clarifications on who is considered a “provider” of an AI model and when a model is “placed on the market”. This includes not only the original creator but also “downstream modifiers” who make significant changes to an existing model. A modification is considered significant if the compute used for it is more than a third of the original model's training computer.

The document also outlines exemptions for open-source models, provided they meet certain conditions, such as public availability of parameters and a lack of monetisation. However, even open-source models must comply with copyright law and provide a public summary of their training data.

Finally, the guidelines set out the enforcement approach. The European Artificial Intelligence Office (AI Office) is tasked with overseeing compliance. Companies that adhere to an approved “code of practice” will be considered to have a straightforward way of demonstrating compliance. The Commission acknowledges that companies may need time to adapt, and has stated that it will give “particular consideration” to those who proactively engage with the AI Office to ensure compliance in the first year of the rules' application.

Want to find out more about FLOPs? Read on: Regulating AI: The Limits of FLOPs as a Metric

CCS organisations denounce Commission’s AI ACT implementation package

A broad coalition of 40 CCS advocacy organisations published today a joint statement voicing their dissatisfaction with the Commission’s recently issued General-Purpose AI implementation package.

A broad coalition of 40 CCS advocacy organisations published today a joint statement voicing their dissatisfaction with the Commission’s recently issued General-Purpose AI implementation package.

They remind the European Commission that Article 53 of the EU AI Act and related provisions were specifically designed to “facilitate holders of copyright and related rights to exercise and enforce their rights under (European) Union law” in response to ongoing, wholesale unlicensed use of their works and other protected content by GenAI model providers. However, the feedback of the primary beneficiaries these provisions were meant to protect has been largely ignored, according to the letter, in contravention of the objectives of the EU AI Act to the benefit of the GenAI model providers that “continuously infringe copyright and related rights to build their models”.

They call the European Parliament and Member States, as co-legislators, to challenge the package process, which “will only weaken the situation of the creative and cultural sectors across Europe and do nothing to tackle ongoing violations of EU laws”.

“Today, with the EU AI Act implementing package as it stands, thriving cultural and creative sectors and copyright intensive industries in Europe which contribute nearly 7% of EU GDP, provide employment for nearly 17 million professionals and have an economic contribution larger than European pharmaceutical, automobile or high-tech industries, are being sold out in favour of those GenAI model providers”.

They denounce that despite months of “extensive, highly detailed and good-faith engagements by the rightsholders communities”, the EU CCS are being “sold out” to the benefit of GenAI companies “that have built their services by infringing EU copyright rules”.

Find the full statement here