CCS are characterised by project-based financing, fragmented value chains, high levels of self-employment and non-standard forms of work. Precarious working conditions and low levels of collective representation make it one of the least organised forms of work, in contrast to its social value as seen during the pandemic. This is the first and main conclusion of a study published by the European Labour Authority on the working conditions of artists and creative workers in the EU.

The study titled "Employment characteristics and undeclared work in the cultural and creative sectors" paints a stark picture of systemic failure, as in many cases cultural workers appear to be left without basic protections such as health insurance and pension benefits. In addition, digital platforms and cross-border mobility complicate their professional environment, with many artists operating in legal and financial grey areas.

The study used a multi-method approach to investigate undeclared work in Europe's cultural and creative sectors, combining desk research with semi-structured interviews with stakeholders in the EU cultural sector. It also included in-depth case studies in five countries: Belgium (Flanders), France, Germany, Latvia, and Portugal.

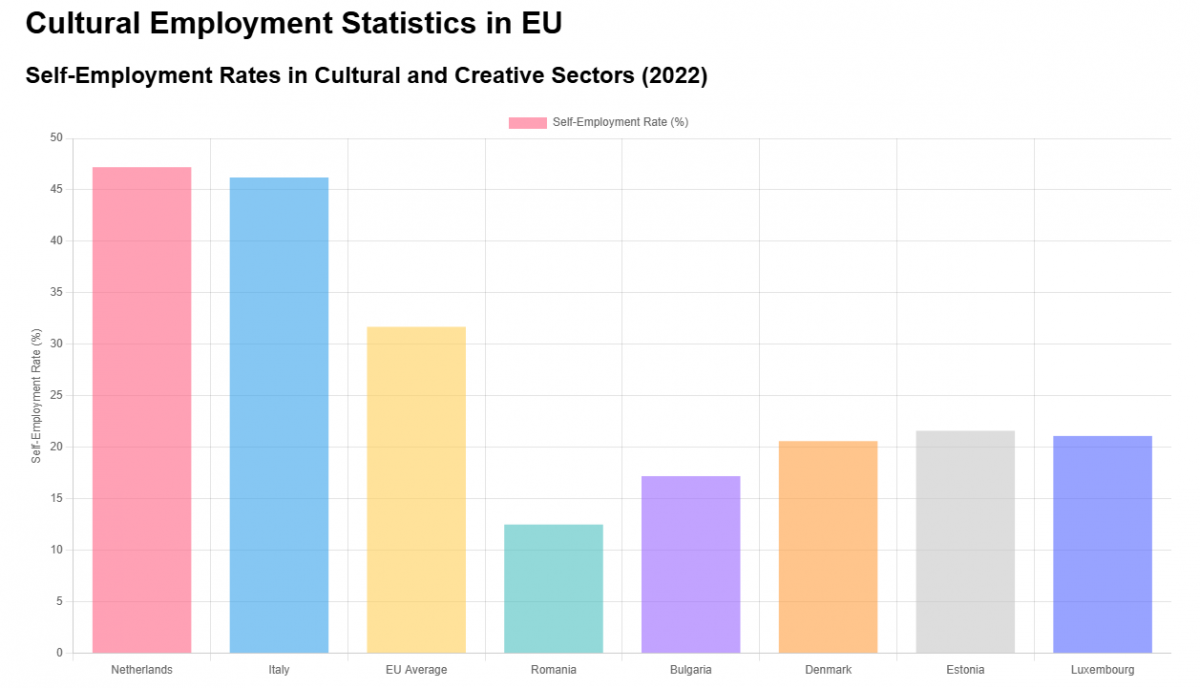

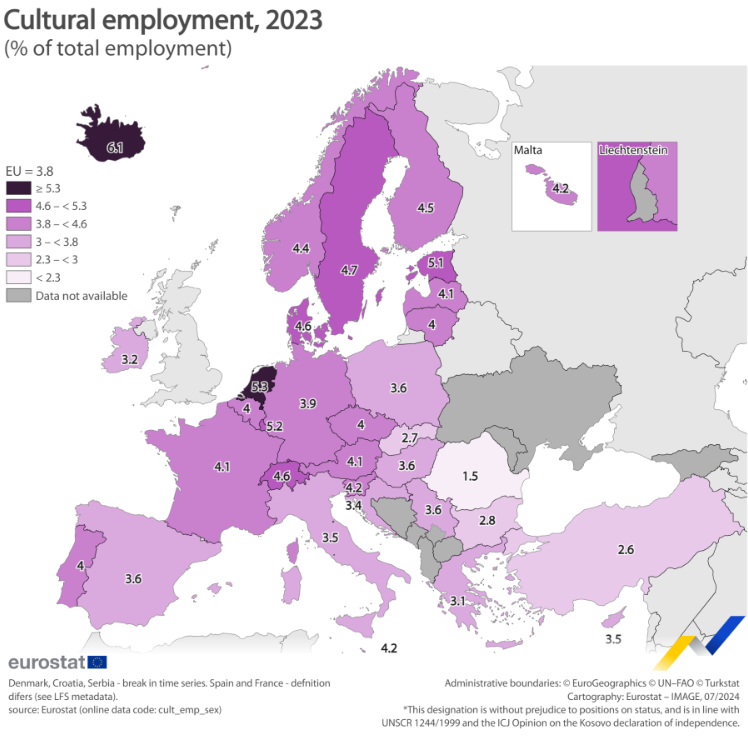

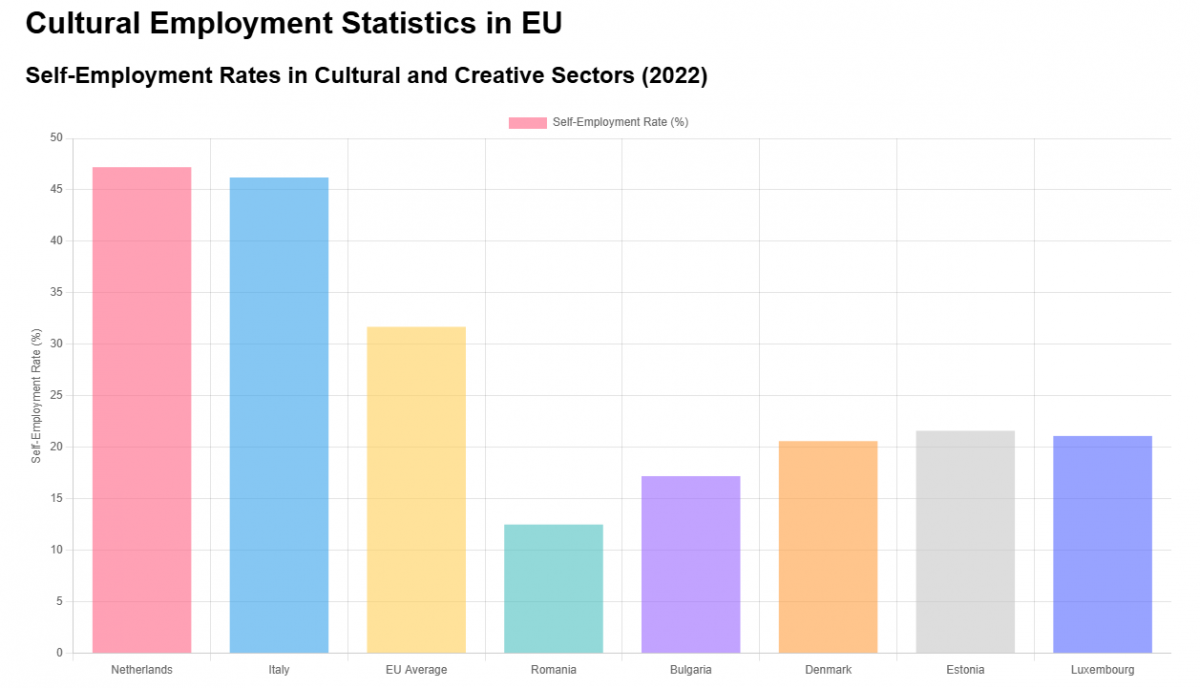

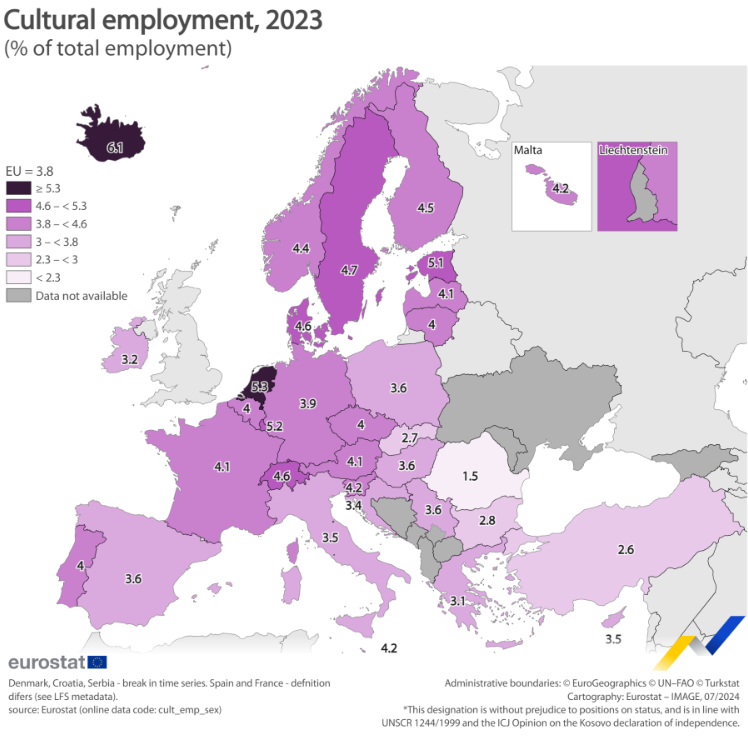

Overall, the cultural sector in the EU employs around 7.7 million people, representing 3.8% of total employment. However, only 76.5% work full-time, compared to an EU average of 81.5% in the wider economy, with particularly low rates in the Netherlands, Austria, and Germany. In addition, almost a third of CCS workers are self-employed, compared to only 13.8% in other sectors of the economy. Artists face particularly difficult circumstances, with only 73.3% having a permanent job, according to Eurostat.

Wide differences among member states but also sectors

ELA, estimates that there should be around 1.2 million cultural enterprises in the EU in 2020, accounting for 5.2% of businesses within the non-financial business economy. There are significant regional disparities, with higher employment in the sector in western and northern Member States than in eastern and southern ones. Germany and France, together with the Netherlands, Spain and Italy, were home to 62.6% of all artists and writers in the EU.

--

The most recent statistics available show that 1.7 million artists and writers were active in the EU, accounting for 22% of employment in the sector. 'Artists and writers’ is measured by Eurostat by means of selecting two specific cultural occupations e.g. authors, journalists, and linguists and creative and performing artists. About 46% of artists are self-employed, which is significantly higher than the proportion of self-employed in all sectors of the CCS (31,7%) and in the total employment (13,8%).

Employment in the CCS is also characterised by higher participation rates of women and younger people, and higher levels of education than in the general economy. But there is also considerable diversity between the different sub-sectors (e.g. literature, music, visual arts, performing arts, audiovisual and cultural heritage); Performers and artists for example, face particularly complex challenges when working across EU borders. Issues such as double taxation, misclassification of workers and inconsistent national regulations create additional barriers. Non-EU nationals working without proper permits add another layer of complexity to this already nuanced employment ecosystem.

Employment Precarity in the CCS

What can be done?

In order to tackle the problem, some countries have taken certain measures. France has introduced regional prevention agreements specifically targeting undeclared work in the audiovisual and performing arts. Belgium has introduced a regulatory framework for both professional and amateur artists, creating more structured pathways for cultural employment.

Countries such as Belgium, France, Greece, and Portugal have established sophisticated registration systems to collect data on cultural workers, providing unprecedented insights into employment dynamics in the sector. In the audiovisual subsector, prior authorisation and event permits have become standard practice, helping to create a more transparent working environment.

A pivotal workshop in Brussels in May 2024 brought together labour inspectorates, social partners, and EU institutions to identify the root causes of undeclared work, develop prevention strategies and create comprehensive policy recommendations. In the September report, the ELA focuses on establishing a standardised framework across Member States.

The approach focuses on facilitating an ongoing dialogue between national enforcement authorities to create consistent definitions and job classifications within the cultural industries — a long-standing problem in the EU. By developing a robust data collection mechanism, experts aim to enable comparative analysis between different countries and cultural sub-sectors.

That should include a particular focus on identifying and documenting current patterns of undeclared work in emerging creative sectors such as video games, sports and the emerging digital creative industries. The proposed strategy also targets less visible forms of undeclared work, including cultural activities organised by casual employers and transactions facilitated by digital platforms.

The rise of digital platforms has further complicated the employment landscape. Professionals increasingly rely on crowdfunding and online platforms, often operating in legal grey areas that circumvent traditional tax and labour regulations.

ELA believes that these recommendations could significantly improve working conditions for artists and creative professionals by developing targeted prevention strategies and creating more transparent employment mechanisms. However, experts acknowledge that successful implementation will require sustained cooperation between government agencies, cultural institutions and creative professionals across the European Union.

--

Image (1) Credit: Graffiti in Via del Voltone by 66colpi, under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International licence

Image (2) Credit: Corso degli Artisti Street Painting Festival in Little Italy, Downtown San Diego, Christopher Mann McKay, GNU licence

Artistic freedom, fair wages and decent working conditions for artists and cultural workers in the G20 leaders' declaration

As the Brazilian Presidency refocused G-20 discussions on global poverty, inequalities, sustainability and climate change, the specific issues of working conditions in the arts and cultural sector and the role of culture in global challenges were highlighted.

The impact of artificial intelligence on culture, copyright in the digital environment, artistic freedom, fair pay and decent work for arts and culture workers are some of the cultural priorities included in the G-20 leaders' declaration in Rio de Janeiro yesterday.

Under the Brazilian Presidency, the summit of the twenty largest economies in the world focused on three priorities:

- Social inclusion and the fight against hunger and poverty

- Sustainable development, energy transition and climate change

- Reform of global governance institutions

On the above objectives the leaders of G 20, recognized “culture’s power and intrinsic value in nurturing solidarity, dialogue, collaboration and cooperation, fostering a more sustainable world”. They also commited to the principles of inclusion, social participation and accessibility, for the full exercise of cultural rights confronting racism, discrimination and prejudice.

The G20 declaration encourages countries to strengthen international cooperation and exchange for the development of the creative economy and reaffirms commitment to the relevant UNESCO cultural conventions.

On copyright, the declaration calls for global engagement in the discussion of copyright in the digital environment and the impact of AI on copyright holders.

For those working in the cultural, arts and heritage sectors, the G-20 leaders call on states to promote cooperation to "address social and economic rights and artistic freedom, both online and offline, in accordance with intellectual property rights frameworks and international labour standards to promote fair wages and decent working conditions".

Finally, the declaration encourages the strengthening of the protection of cultural heritage, including historical monuments and religious sites, and supports an open and inclusive dialogue on the return and restitution of cultural property.

A week ago in Salvador da Bahia, the culture ministers of the twenty largest economies signed their declaration with the ambition to advance culture as part of the multilateral agenda.

The ministers of culture of the G 20 highlighted the role of culture “as an enabler and driver for sustainable development, and its potential to contribute directly and indirectly to the implementation of the sustainable development goal”. They also recognized the great potential of culture to bring forward climate action and more specifically:

- to encourage building on the opportunities of culture-related transformative practices

- to inform climate adaptation and mitigation strategies as well as solutions for climate actions

- to promote the necessary actions with regards to climate change

- to protect cultural and natural heritage from the impacts of climate change

- to stimulate more sustainable cultural practices

The declarations of the G-20 meetings include general principles, calls and reaffirmations in critical areas of political, social and economic life, which are non-binding but indicative of the stance and orientation of global governance.

--

Photo: Mirta Toledo

Photo source

False self-employment, no contracts, and unpaid services: cultural and creative workers' secrets?

A pilot study by the European Labour Authority reveals significant undeclared or under-reported work in the cultural and creative sector in European Member States.

Undeclared or under-declared work seems to be a common secret in the cultural and creative sector (CCS). However, this is of little relevance to national policy makers. A pilot study by the European Labour Authority (ELA) aims to provide the first mapping of this relatively untouched area.

Although data and statistics on this issue are limited, participants in the Platform's Thematic Review Workshop (Brussels, May 2024) confirmed that, in line with their experience, there is significant undeclared work in the CCS in Member States. This can take various forms, such as bogus self-employment, cash payments, lack of written contracts, unpaid or underpaid services. In addition, the lack of dialogue between employers and workers and fragmentation appear to be further obstacles to improving working conditions in many subsectors and fair pay for cultural and creative workers.

Journalists, web designers and performers are among the professions most affected by bogus self-employment. Other forms of undeclared work are found among creative professionals, circus artists, DJs and support staff .

Un(der)paid services and activities

A specific feature of working conditions in the cultural and creative sectors that emerges from the research and literature is the activities that cultural and creative workers carry out without receiving any form of payment or financial compensation.

Research findings indicate that cultural and creative workers in general spend time on various types of activities for which they do not receive financial compensation. In the live performance sub-sector, such 'unpaid' activities include networking, writing applications for funding, conceptualising new projects, completing projects, administration, etc.

A similar phenomenon can be observed in the audiovisual sub-sector. Musicians often spend a lot of time practising their professional skills. Film and documentary directors and scriptwriters provide services that are not fully remunerated (e.g. development work, scriptwriting, pre-production preparation, but also peer coaching and even teaching).

Nevertheless, there seems to be a growing awareness of the issue of unpaid work among stakeholders and policy makers in the Member States. For example in Germany, rehearsals and performances are typically considered as part of the paid services or artistic work activities in the live performance sector. In addition, artists (e.g. dancers, orchestras, theatre actors, etc.) are increasingly demanding written contracts and adequate remuneration for their rehearsals and performances.

Bogus self-employment

According to the research, a significant number of professionals in the CCS who are technically self-employed are de facto in dependent employment and thus in 'false self-employment'.

Cultural and creative sector organisations rely on public and private funding to finance their operations, while at the same time requiring the availability of professionals in order to receive such funding. This leads to project-based employment and contributes to an increased reliance on non-standard forms of work to cut costs. For example, artists and creators who are contracted by a single person or organisation to do work for them are declared as self-employed, even though the hours of work, the content of the work and the way it is handled are determined by the contractor and not by them.

Depending on the measurement method, bogus self-employment is estimated to be between 1.6 % and 10.8 % of all self-employed in the CCS. As a result, the CCS is one of the economic activities with the highest shares of false self-employment in the EU.

In this context, the authors of the study highlight the difficulties of establishing an employment relationship in cases where third party payers are involved and performers work, sometimes for very short periods, in small venues without the clear 'presence' of a direct counterpart who may in some specific cases be qualified as an employer.

The absence of a direct counterpart at the place of work may also have consequences in terms of compliance with legislation on working conditions and occupational health and safety. This specific issue, which concerns the live performance sub-sector, was also raised during the Thematic Review Workshop.

Absence of written contracts and cash payments

The information gathered from interviews and desk research also highlights the phenomenon of workers in the cultural and creative sector providing work without a contract. This does not mean that the work is not paid for by the client or employer. However, it appears that a significant amount of time is spent by workers performing a task without 'adequate' financial compensation. In some cases this may mean that there is no contract for these hours or that the hours worked are under-reported.

The interviews also revealed the existence of a certain informal economy, the acceptance of cash payments and unregistered services. This is very often associated with small-scale activities and/or small private venues.

Read the full report here.

--

Photo author: Mostafameraji

Photo source

"Don't accept precarious working conditions as inevitable"-A Conversation with Joost Heinsius

By highlighting previously unaddressed issues such as false self-employment, unpaid and underpaid working hours, and the lack of collective bargaining, the ELA exposes the sector's fragmented nature, where only three sub-sectors maintain regular social dialogue between workers and employers. Expert Joost Heinsius speaks to Creatives Unite about the need to address informal work in the CCS both on the advocacy and the policy level.

The European Labour Authority's study reveals the precarious reality of Europe's creative cultural sector, exposing systemic challenges of false self-employment, fragmented labour dialogues and persistent underpayment. “What makes the implementation of a unified artist status so challenging is the complexity of creating a comprehensive framework that works across different artistic disciplines and national systems,” argues policy expert Joost Heinsius*. As artists and creative professionals navigate increasingly complex working landscapes, he says, the need for comprehensive policy reform becomes urgent. How can the ecosystem effect positive change? “The key is collective action — workers uniting, developing independent platforms and keeping pressure on employers and global platforms.” Read the full interview:

Q: Is the ELA study hitting what we empirically all know to be the case, but authorities still need to recognise?

A: I think it is revealing something that we all empirically already know. However, the topic is on the agenda, but national governments and EU institutions do not seem to be able yet to solve the problems arising from this empirical knowledge. The European Labour Authority has never looked at the CCS until now. They mostly looked at sectors with formal labour relations, not declaring their hours, etc. For them, the Cultural Creative Sector is completely new. That being the case, they are drawing attention to several key points:

— Figures on national and European levels don't follow the same definitions, making it hard to get statistically sound figures.

— They're stressing new terms and numbers to the discussion, like false self-employment, being underpaid or having unpaid hours.

— They're highlighting the fragmentation of the sector, noting that only three sub-sectors have a regular social dialogue between workers and employers and principals.

“Most self-employed workers lack collective bargaining power, which hinders their ability to negotiate better pay rates, and that is particularly relevant in the CCS”-Joost Heinsius

Q: How can the classification problem be solved, given that both Europe and the labour sector are trying to create categories that don't necessarily match?

A: It's challenging because authorities like Eurostat are reluctant to change their definitions. If they take a step to modify their methods, everything they've done before becomes potentially irrelevant. The same applies at the national level—each jurisdiction wants to maintain its existing research and statistical frameworks. Essentially, Eurostat tries to fit national-level data into European-level categories. This discussion has been ongoing for 20–30 years and hasn't been solved yet.

Q: What does this difficulty mean practically for artists and the production of culture?

A: Not much. People will continue to make art and culture regardless of classification challenges. The real impact is on how the sector is understood, supported, and regulated by policymakers and advocacy. It matters when trying to understand sector conditions, develop progressive working conditions, or build collective bargaining power. Artists will continue creating art under any classification system.

Q: There’s a long debate about the need to recognise the status of the artist across the EU and certain guarantees that come with it. Is it coming closer to becoming a reality?

A: It's a gradual process. Currently,a little more than half of the member states have some kind of artist status, but it's always partial—covering only small areas of social security or labour. In the future, probably within 4-10 years, there might be a framework for working conditions. This could come partly through the European Social Pillar, which has principles about equal access to social security, equal pay, and gender equality. However, the major challenge is that all member states must agree, which makes it a slow process.

“The sector has experienced massive growth over the past 10–20 years, but this growth has led to increased precarity” — Joost Heinsius

Q: What are the current working conditions for artists across Europe? If one believes ELA, then it seems that if you're an artist in Europe right now, you are likely to work two jobs, with one potentially outside your sector, be self-employed, or operate as a one-person company. You may be underpaid or even lose money and experience unstable working conditions. What is more striking is that this is true even in vibrant industries like television and film. For example, among directors and screenwriters, many need a second job. This isn't just happening in niche areas but in active, dynamic sectors. But are these conditions similar across different European countries?

A: No doubt, the situation is complex, and conditions differ significantly between countries and professions. For instance, the Netherlands has surprisingly high self-employment due to its labour traditions, while other countries might have other challenges for artists. Then the experience of a music manager versus an actor can be vastly different. What makes implementing a unified artist status so challenging is the complexity of creating a comprehensive framework that works across different artistic disciplines and national systems. The process is inherently slow because it requires aligning multiple perspectives, legal frameworks, and economic realities across different European countries. Europe is slow, but it cannot be done otherwise.

However, this is a paradoxical situation. The sector has experienced massive growth over the past 10–20 years, but this growth has led to increased precarity. More people want to work in creative industries, which unfortunately drives down pay rates and increases competition.

Q: Could you elaborate on how this competition affects artists and creative professionals?

A: It's quite simple: with so many people wanting to work in these sectors, employers, and principals can easily offer low rates. Platformization in the digital world has further intensified this competition. Whether it's in film, music, or design, professionals often find themselves working multiple jobs, with many earning significantly less than they should. The digital ecosystem is dominated by a few global players—primarily American and Chinese platforms. These platforms have created near-monopolistic conditions. European cultural producers have become increasingly dependent on these global marketplaces, which compromise our cultural diversity and independent production.

Q: What can the European Union do to address these challenges?

A: We're seeing efforts to develop a comprehensive framework for artist working conditions. About half of EU member states have partial artist status regulations. I expect in the next 4–10 years, we might see more comprehensive guidelines covering social security, fair payment, and working conditions. Joost: This is already being said before…

Q: As you describe the landscape in the CCS, I am wondering if there is any room for optimism.

A: Definitely. Europe is still leading in some areas, particularly in AI regulation. Global digital platforms are reshaping our cultural production, but European institutions are working to protect our cultural diversity. Change will be gradual, but it's possible through persistent, strategic efforts.

“Workers uniting, developing independent platforms, and maintaining pressure on employers and global platforms. We're not defeated; we're adapting”-Joost Heinsius

Q: But on the practical, everyday level, what would you advise individual artists facing these challenges?

A: Unite. While individual experiences vary dramatically between countries and sectors, solidarity can create meaningful change. Don't accept precarious working conditions as inevitable. The key will be collective action—workers uniting, developing independent platforms, and maintaining pressure on employers and global platforms. We're not defeated; we're adapting.

--

*Joost Heinsius is an independent expert specializing in the working conditions of artists and cultural professionals. With over 25 years of experience in the cultural sector, he currently works as an expert for the Creative FLIP project. Joost has led several prominent projects for European institutions, including research on crowdfunding in the cultural sector and the impact of COVID-19 on creative industries. He is also a lecturer, writer, and advisor with a diverse background in political science and journalism.