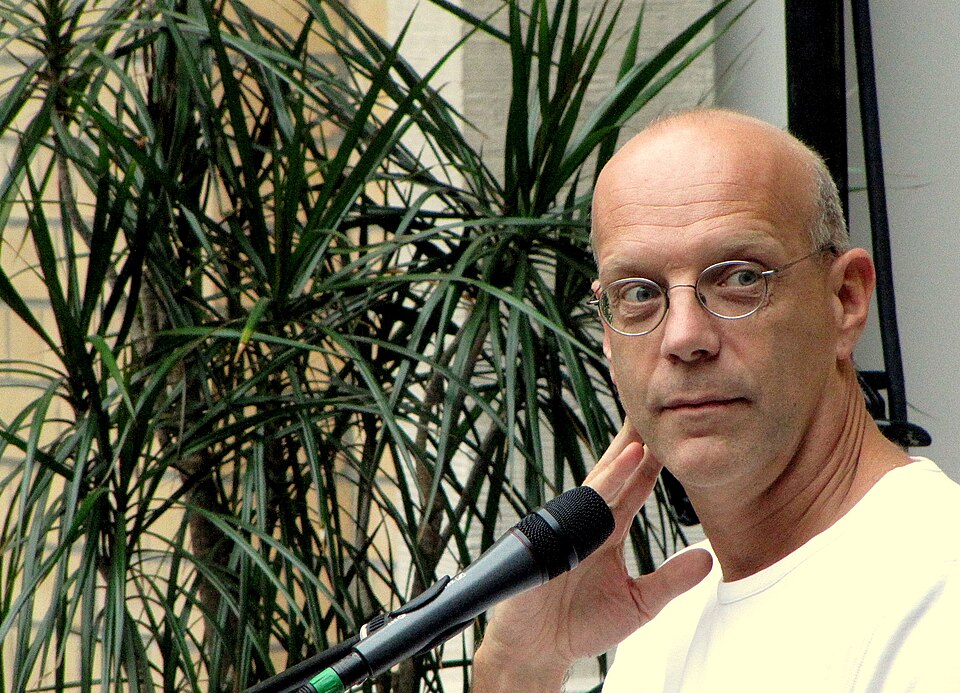

Geert Lovink is a Dutch media theorist and critic of digital culture known for his extensive work on internet studies and digital media. He is the founding director of the Institute of Network Cultures (INC) at the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences. Lovink has authored several influential books, including Dark Fiber, My First Recession, Zero Comments, and Networks Without a Cause. Most importantly, he has been an active figure in digital culture since the 1980s, co-founding important initiatives such as the Digital City Amsterdam community network and the nettime mailing list. He also served as a professor at the European Graduate School and the University of Amsterdam, contributing to research and academic discourse on media, internet culture, and new media criticism.

Geert Lovink's latest book, titled “Platform Brutality: Closing Down Internet Toxicity”, was published in 2025 by Valiz. The book addresses the toxicity of the internet, focusing on the harms caused by monopolistic platform capitalism. It is an urgent appeal for collective withdrawal from the toxic digital environment, engaging critically with the social and economic impacts of dominant internet platforms. This work follows his earlier 2022 book, “Stuck on the Platform: Reclaiming the Internet”, where he proposed movements to dismantle platform monopolies altogether and reconstruct the internet as a public infrastructure.

We sat down with Geert at a café in Athens to discuss the seismic shifts happening in our lives with the widespread use of AI LLMs. He sees the hype around AI as distracting from the real issues, such as platform addiction, misinformation, and the concentration of power in large digital platforms. Lovink highlights how internet platforms have shifted from facilitating free, empowering use of the internet to creating dependency and addiction. He warns that this leads to loss of control over communication terms, social interaction, and public debate, emphasising the social and political consequences of this algorithmic environment. This critique is central to his latest book, “Platform Brutality”, which diagnoses the digital condition as one of platform-induced toxicity and dependence and calls for collective withdrawal and dismantling of the current platform ecosystem. Over coffee, he laid out a sobering vision of where the internet is heading—from the intended confusion around AI to the brutal reality of platform dependency.

Let's go straight to the topic we're discussing: AI. If I may say so, it's a dead language.

Yes, it is. I don't use the term 'AI'; I prefer 'large language models' or 'machine learning' because AI is neither intelligent nor artificial. Start-up entrepreneurs and investors benefit from this confusion, especially the fear that comes with it. There's fear of people losing their jobs, fear of losing our cognitive capacities because machines are going to think for us, and so on. This is well known in the ethics industry as one of the main drivers of the AI machine itself. Instead of providing a radical critique, ethics are part of the problem.

I can’t help but think that, with social media already in place, we’re breaking stories down into smaller pieces and talking about non-linear narratives. This has had a profound cognitive and neurological impact on us.

The hype surrounding AI is preventing people from considering the consequences of its use. In fact, the hype is so intense that people feel they are no longer using the internet, but AI. However, from the perspective of internet platforms, the first question is always about media attention, which is one of the main drivers of the whole thing. Platform addiction, fake news and the question of how social interaction and communication through digital tools should look then follow. For young people and some professionals, LLMs are indeed partly replacing search engines today. LLMs have many similarities with search engines; instead of typing queries, you articulate them as prompts. The difference is that the application remembers who you are and what you asked before; it records and processes conversations you have with it. It thus builds on the condition of the platforms.

Large platforms themselves are now undergoing structural changes due to AI. AI is already a feature of Google’s front end, but an even greater feature of the back end.

It stops the idea of 'options'. You ask a question on the platform, and it comes back to you with thousands of answers. It was never possible to browse through them, and this was a questionable feature from the beginning of the internet. Over time, search engines like Google started to rely more and more on Wikipedia because it could provide a brief summary. Rather than just presenting links, it started providing answers. What is quite remarkable about AI is that this tendency is accelerating. Now, you only get one answer and, within that answer, you will probably encounter some choices or ambiguities as the narrative machine synthesises it. It presents itself as objective, packaged inside a personal approach, but it always tries to 'cover its back' and not appear scientific. Instead, it will appear accessible and have a human side.

Living in the golden era of marketing, where everything is bite-sized, I can't help but think that, with Wikipedia, there's still a human element to the process. The LLMs imply a divine element. The model has scanned all the relevant information and provided a personalised response just for you.

One of the problems is that the notion of truth no longer exists. As the model presents itself as human, it doesn't just provide facts; it also offers advice. This advice can even have emotional characteristics because it is based on your previous interactions with the system. We are familiar with the concept of filter bubbles from social media. These bubbles provide unchallenging answers that tend to confirm one's existing beliefs.

The issue with AI is that it takes this process a step further, leading to greater concentration of power. It's still early days, but significant investments have already been made and need to be recouped. This is the crucial question on the table. How will we pay for all this?

It took 20 years to realise that the business model of large online platforms is based on the media model. They're just not national media outlets. They are not subject to any constitutional guarantees. For example, they still sell adverts.

I think so too, but they have not yet figured out exactly how the advertisements will fit in with AI.

So we're moving from post-truth regimes to what?

In my new book, Platform Brutality, I make two observations. First, the internet is moving away from offering free services to facilitate your life. Up until now, you could download an app, create a profile and get started right away. Users want to achieve something: 'I want to connect with my friends', 'I want to become an influencer'. The internet has facilitated all these ambitions for empowerment. However, this era is coming to an end. The medium may not be imploding yet, but we are getting very close to that point. We've gone from free, open facilitation to dependency and addiction. I hesitate to label the vast majority of people online as addicts or junkies. Clearly, there is a need. Dependency on social media emerged at a time when humanity crossed a threshold for the first time: more than half of the population now live in urban centres. Urban centres require very close coordination. Where is the mother? Where are the children? Where is the family? What about the tribe, the neighbourhood and wider social contacts? Are they all right? Are they in charge? The idea that people can live chaotic and stressful lives in large urban areas without some kind of control or coordination is romantic. It's just not possible.

People are using these social platforms for that purpose. That's where the problem starts. They are not using the internet, but rather very specific architectures: Facebook, WhatsApp, and so on. This comes with an enormous amount of noise — basically, advertisements.

"The internet is perhaps the mistake of my generation; we still thought that people were in charge somehow. That idea was naive."

Take the idea of having to like and follow your family members, for instance. The whole cultural logic of following, sharing, and liking doesn't make sense. It's all nonsense. But people cannot get rid of it. This is the concern. They sign up for these vital communication devices and, with them, an enormous amount of unnecessary functions. Or maybe the lack of certain functions is because they are not in the interest of Meta and Google. While the internet may facilitate them, these companies are not interested in them. And we cannot change that. The internet is perhaps the mistake of my generation; we still thought that people were in charge somehow. That idea was naive. In libertarian terms, this is often phrased as people losing their privacy. I would argue that people have lost the ability to define the terms under which they communicate. Simply put, why would you communicate with Taylor Swift in the same way as you would with your mother or friends at the football club? It doesn't make sense. But these systems cannot distinguish between the two.

We're talking about an algorithmic environment which is not public

No, no, in fact, it's completely private.

But it does facilitate public debate

It's the perfect tool for world-making. It creates the world for you, in front of you, on your device. What's more, it analyses the way you scroll or swipe. Then it makes slight changes, constantly suggesting new things. This is how people get sucked into these rabbit holes with no way out. You can't just reset these algorithms and say, 'Okay, I've had enough.' The machine does not forget. It will continue in the same direction tomorrow.

That has social and political repercussions, doesn't it?

Indeed, it is not truly governed by a logic of choices. The idea of having a world view that considers the perspectives of others is becoming so irrelevant that it is completely out of the question.