A new report by the European Research Council (ERC) — Mapping Frontier Research on the New European Bauhaus (2025) — shows how that vision is already taking form. The publication presents 87 ERC-funded research projects worth €158 million, each connecting scientific discovery with societal transformation.

“Together, these discoveries provide a glimpse of what’s possible when frontier science meets societal ambition,” writes Professor Harriet Bulkeley, member of the ERC Scientific Council. “Places that are not only sustainable and inclusive but also inspiring — for today and for generations to come.” Launched in 2021, the New European Bauhaus (NEB) is the creative wing of the European Green Deal — an effort to ensure the continent’s ecological transition is also a cultural one.

Inspired by the original 1919 Bauhaus movement that united art, design and industry, the NEB recasts this vision for the age of climate change, focusing on three inseparable values: aesthetics, inclusion, and sustainability.

The ERC report provides the most detailed mapping yet of how frontier research across Europe is advancing these values, demonstrating how scientific curiosity can transform cities into living laboratories of innovation and belonging.

“By bridging science and technology with art and culture,” the report states, “the New European Bauhaus turns creativity and innovation into practical transformation.” From self-healing building materials and solar façades to housing justice and participatory design, each project reflects the same vision: cities that are sustainable, inclusive, and inspiring.

The Mapping Frontier Research on the

New European Bauhaus report concludes that Europe’s most advanced science is not only technical but civic — grounded in collaboration across disciplines.

Building Beauty Beyond Function

The report’s first section, Aesthetics, looks at how architecture and materials science are changing the texture and feeling of cities. The focus: creating spaces that are both sustainable and sensorially rich. In Slovenia,

Anna Sandak and her team at the University of Primorska are turning walls into living organisms. Their ARCHI-SKIN project develops

Engineered Living Materials (ELMs) — fungal biofilms that can grow, adapt, and repair themselves. “Our technology has strong potential to transform surface protection in architecture,” Sandak says, “offering coatings that are self-regenerating, non-toxic, and environmentally responsive.”

In Denmark, Mette Ramsgaard Thomsen’s project

ECO-METABOLISTIC-ARC explores biomaterials like bioplastics and bioluminescent bacteria, envisioning architecture as a “living and changeable entity that requires maintenance and care.”

The Italian project

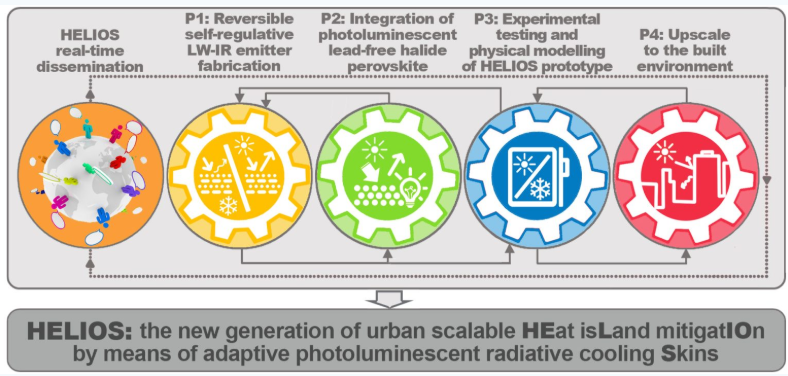

HELIOS, led by Anna Laura Pisello, aims to cool cities through radiative materials that reflect sunlight and heat. The HELIOS project is developing various temperature-responsive building materials aimed at mitigating the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect and improving energy efficiency. These include carriers using lead-free halide perovskites, albedo adaptive photoluminescent finishes, and bio-inspired radiative skins designed to adapt to environmental conditions.

(Click image to enlarge).

Cities That Belong to Everyone

The second pillar of the New European Bauhaus is inclusion — ensuring that cities are equitable, accessible, and socially cohesive. At the University of Oxford, Ben Ansell’s

WEALTHPOL project studied how property ownership shapes political attitudes. “The problem for people who would like more houses to be built or money to be redistributed,” Ansell observes, “is that in almost every location in Europe, homeowners are a majority of the electorate. So rising unaffordability makes these homeowners even less likely to support mitigating policies.”

For Marianne Maeckelbergh’s

PaDC project at Ghent University, housing is a matter of citizenship.

“People cannot function as full members of society when they live in unstable housing,” she writes. The research links the housing crisis to decades of financialisation and weak renter protections. “Understanding housing as a collective matter, as being about communities,” Maeckelbergh argues, “would allow for a foundational transformation in housing policy.”

Culture, too, plays a critical role. The

ARTIVISM project, directed by Monika Salzbrunn in Lausanne, explores how artistic practices — from carnival parades in France and Italy to murals in Los Angeles and street art in Cameroon — become “spaces of civil resistance and critique of top-down urban planning.”

The SEGUE project, led by Clémentine Cottineau at Delft University of Technology, examined urban income segregation in the Netherlands. The findings reveal that while inequality and segregation have remained stable or declined in many cities, “significant differences exist between them.”

Accessibility and belonging extend beyond the home. The InclusivePublicSpace project, led by Anna Lawson at the University of Leeds, investigates “the legal and social justice problems which arise when city streets are designed in ways that exclude or marginalise pedestrians.” The team’s findings include guidelines and immersive 360° videos revealing the barriers faced by disabled and elderly citizens.

Towards Circular and Regenerative Cities

Sustainability is the strongest theme in the ERC portfolio, covering half of the projects. Here, research spans from climate-responsive architecture to food-sharing economies. Food systems also feature prominently. The

SHARECITY project, led by Anna Davies at Trinity College Dublin, mapped more than 4,000 food-sharing initiatives across 100 cities and created the SHARE IT online toolkit to help communities evaluate their sustainability impact. The project shows how “food sharing fosters social cohesion, reduces waste and supports circular economies.”

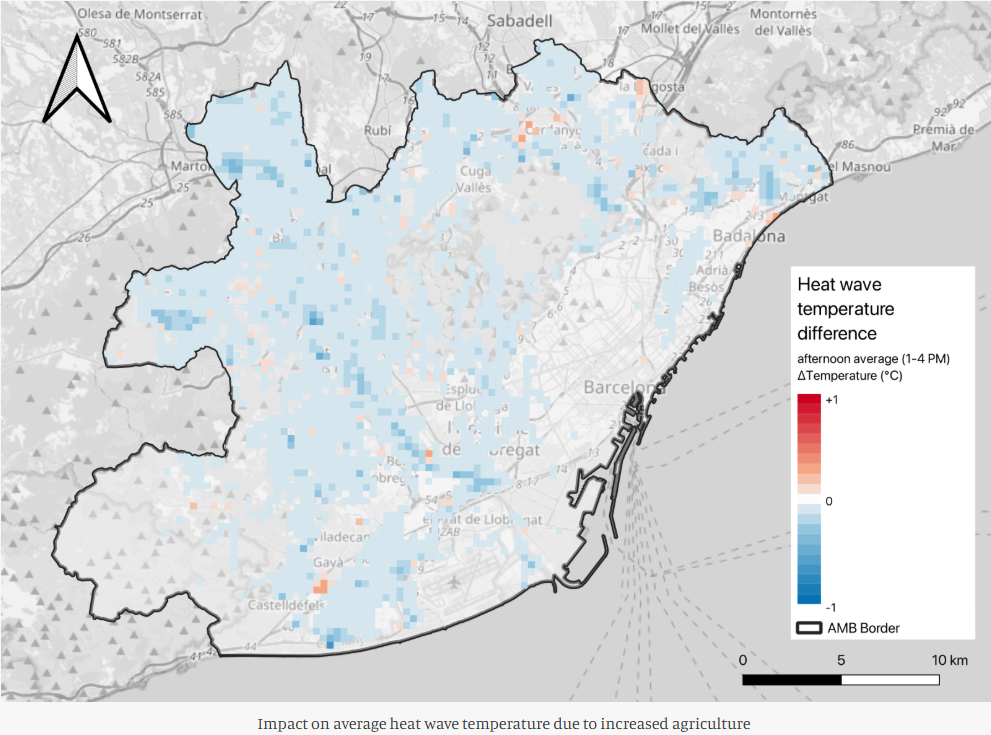

In Barcelona, the

URBAG project, led by Gara Villalba, quantifies how urban green infrastructure — from parks to peri-urban agriculture — affects greenhouse gas emissions and air quality. Meanwhile, Marcus Collier’s

NovelEco project in Dublin studies citizens’ engagement with urban wild spaces. “An emotional bond with wild spaces,” Collier writes, “can be a catalyst for transformation, helping to shape a more sustainable urban future.”

(Click image to enlarge)In Sweden, Oksana Mont’s

Urban Sharing project analysed sharing practices in cities including Amsterdam, Seoul and Toronto, producing governance frameworks now used in Swedish municipalities. “These frameworks,” the report notes, “help cities embed sharing economies into sustainable urban development.”