By Hester Underhill

Charles Sandison was in his early teens when he got his first computer. Purchased from a neighbour for ten pounds and a stack of magazines, it was such an early model that there weren’t even any games that it could be used to play. Instead, the young Sandiford amused himself by programming it himself by typing out different codes he found in a book. “In some way, it became an outlet for my teenage angst. I’m sure if I’d had an electric guitar I would have been banging away on that to get rid of some frustration. But I think, instead, I unconsciously poured my woes and questions into this little machine.”

Growing up in the remote wilds of the Scottish Highlands in the early 1980s, the computer became something of a lifeline. “It was a very isolated place to live. I didn’t have any friends nearby. So that computer became like my best friend.” Little did he know that this early introduction to computing would shape the entire course of his life. Sandison would go on to make his name as a pioneering digital artist, lauded for his use of computing to blur the boundaries between code and canvas and create work that’s often described as “poetry of light.”

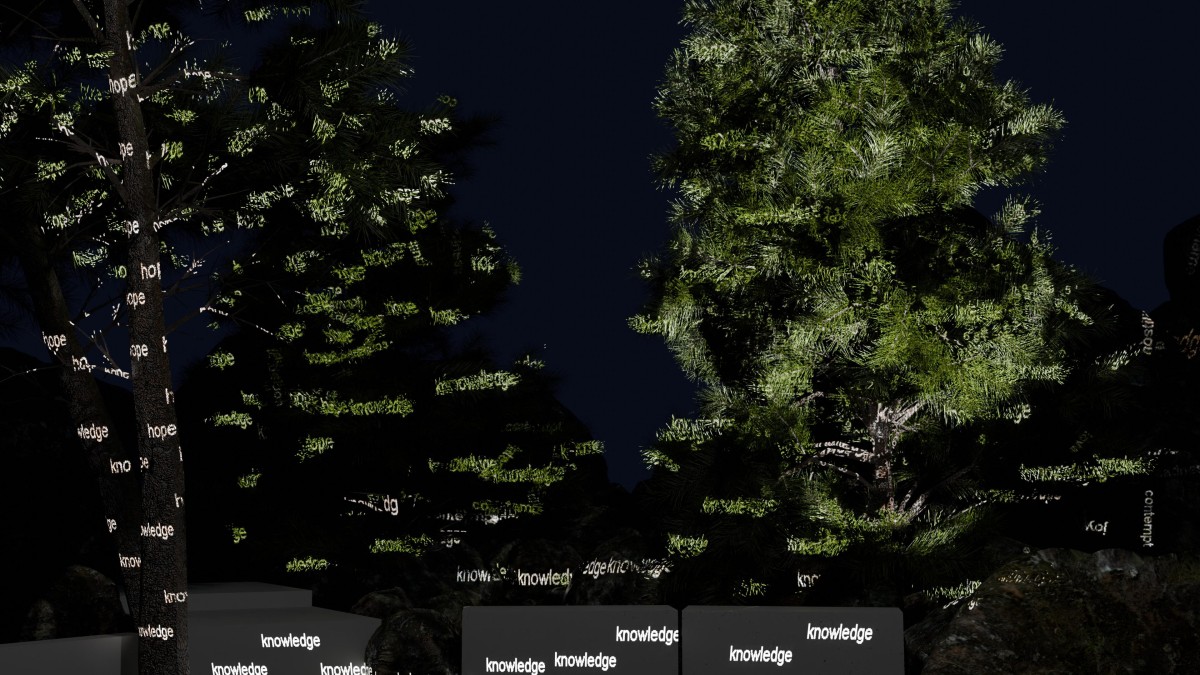

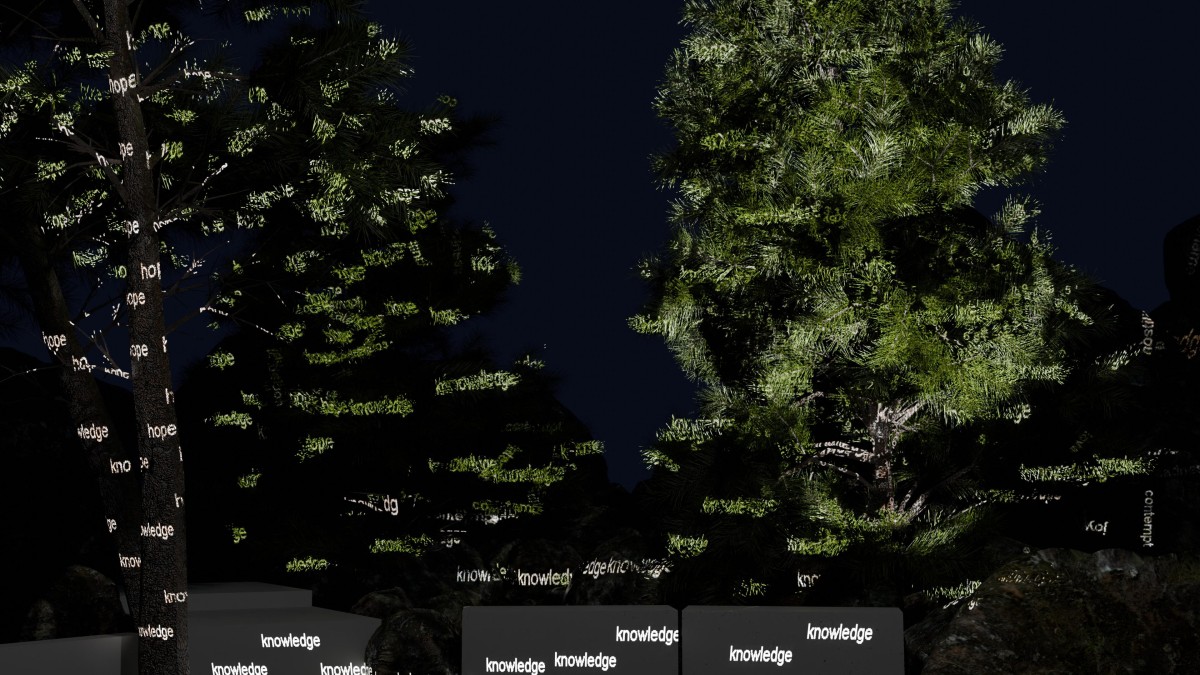

Over the course of his career, which has so far spanned more than two decades, Sandison has made a name for himself through his unique visual style that often involves projecting words and images onto buildings, walls, or even natural landscapes. One of his most recent projects, The Garden of Pythia, was a site-specific installation commissioned by Greece’s Polygreen Culture & Art Initiative (PCAI). Inspired by the Oracle of Delphi, where ancient Greeks would head to receive divine prophecies, the work was on display during this year’s Delphi Economic Forum. It was projected onto the terrain surrounding the centre where the talks and conferences were taking place —trees, rocks, and even animals that might wander into view— transforming the environment into a living, breathing oracle. “The idea is to harmonise everything,” he explains. “Words appear on the trees and rocks, making it look like they’re talking. They’re telling a story, almost like the Oracle itself.”

To create such work, Sandison builds his own software from scratch. “It kind of gives me the possibility to manipulate data and text at a very molecular level.” In doing so, the Scottish artist manages to carefully engineer digital imagery where every miniscule movement and visual detail is the product of an intricately crafted code. “I’m using computational algorithms in an abstract way. Rather than using them to predict stock markets or weather forecasts, I’m using them to predict matters of the human heart and soul.”

Finding ways to translate this sense of soulfulness into a digital form is something Sandison has spent decades honing. Living today in Tampere — a small Finnish city sandwiched between two lakes and surrounded by boundless forests — he still finds great inspiration in the natural world. “I enjoy poetry. If I were Wordsworth, or some kind of lyrical poet, I would wander around the landscape looking at the daffodils and birds and then go back to my studio and write a poem about it. Instead, I get back to my studio and I start writing algorithms which simulate water movements, or the movement of ants across a forest floor. It’s still poetry. I’m still having a response to nature.”

Sandison has been living in Finland now for more than 20 years, having moved there almost accidentally in the early 2000s. After graduating from the Glasgow School of Arts, his plan was to move to Berlin. But a fortuitous invitation to take part in an exhibition in Finland meant he got waylaid on his way to Germany. “I was only meant to be there for two weeks, but I totally clicked with the place. The landscape was incredible. We were staying in a commune next to a big lake. Two weeks turned into three weeks, then four. Then I just decided to stay and get a job.”

Always at the vanguard of digital art, Sandison sees AI’s entry into the creative sphere not as a threat, but as the next frontier—another tool to explore the poetic possibilities of code. “I’m very pro-AI as a creative tool,” he says.

“What really fascinates me is the ability to write code more efficiently and effectively. What would once take me a month now takes me a day. It’s like having a collaborative partner. It’s literally a mind-expanding drug kind of experience.” He warns, however, that the challenges AI poses are more philosophical than technical. “We’re going to abandon some long-held ideas of authenticity and ownership. Or even value. The problem is not with AI, the problem is with our value systems, and how they’re being challenged by this.”

For Sandison, the role of the artist is clear: to question and adapt. “As creatives, we have to engage with AI. If we’re totally defensive against it, I think we risk missing a really important tool for creativity.”

Images:

1. Installation view of PCAI’ newly commissioned artwork the Garden of Pythia by Charles Sandison, in “pi” (Global Center for Circular Economy and Culture) in Delphi, Greece. Photo: Maria Toultsa & PCAI

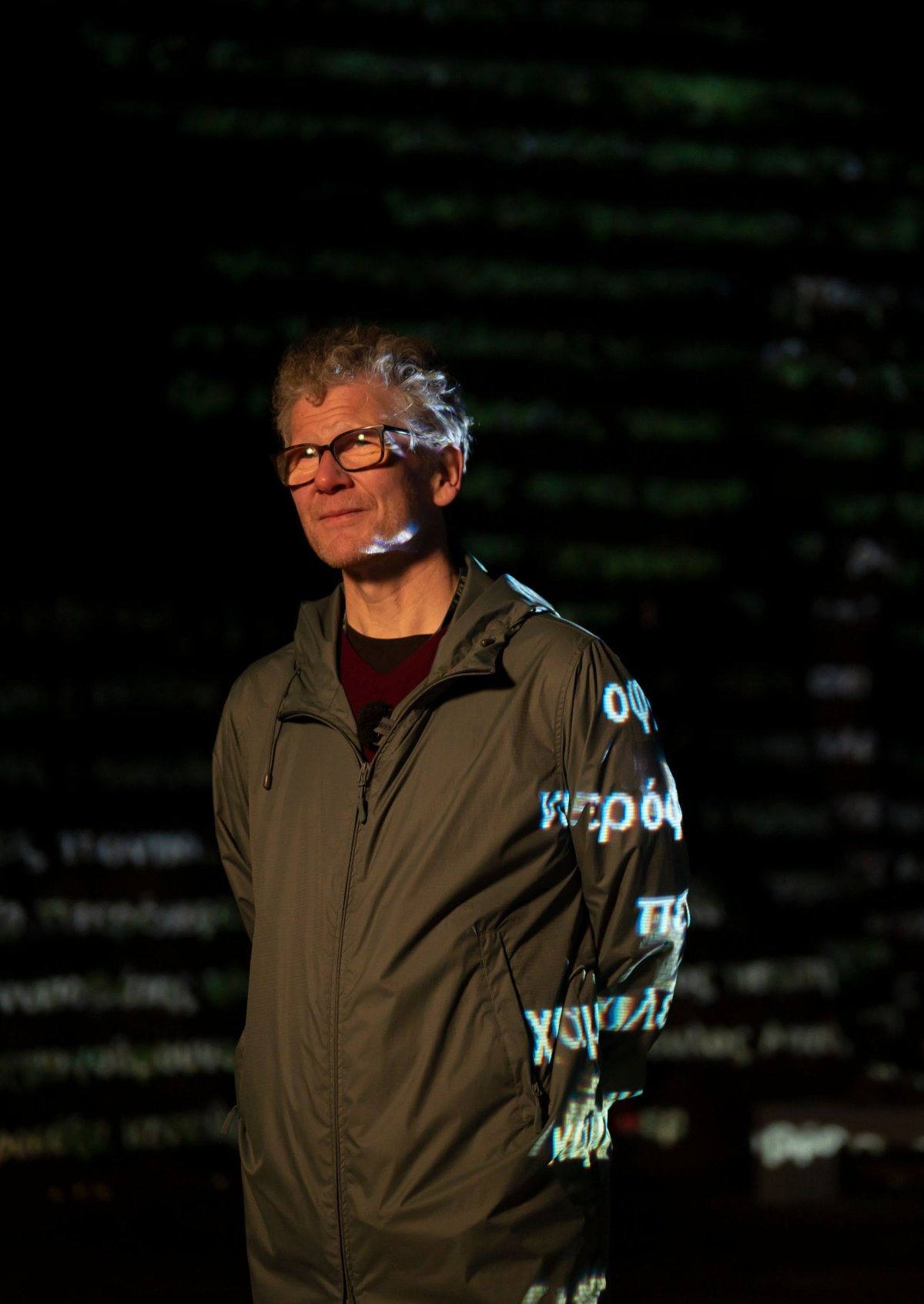

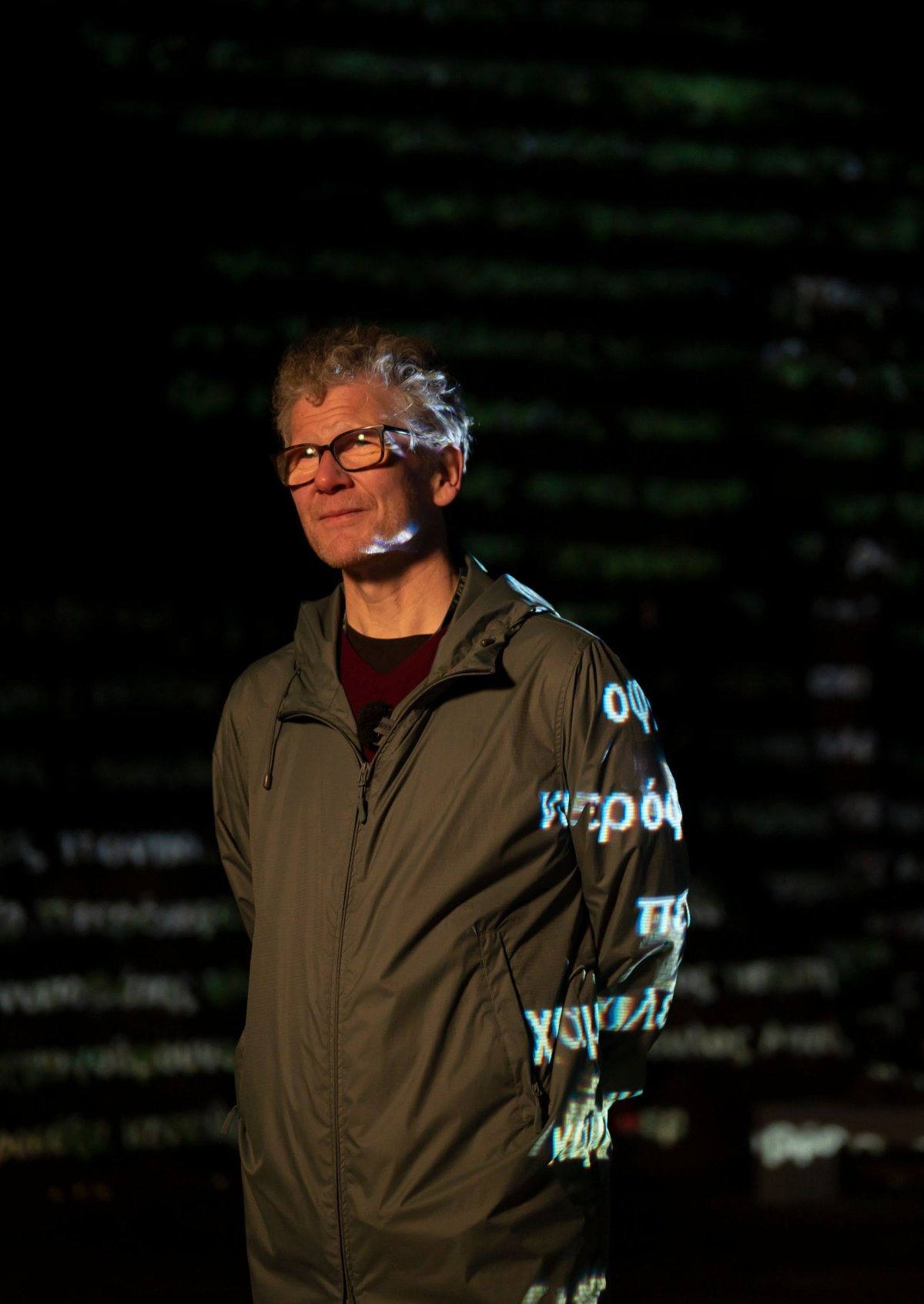

2. Charles Sandison. Photo: Maria Toultsa & PCAI

3. View of “pi” Global Center for Circular Economy and Culture, Former Pikionis Pavilion, Delphi. Image courtesy of PCAI.

4. Charles Sandison, Garden of Pythia, 2025 (work in progress). Courtesy of the artist. PCAI artwork commission

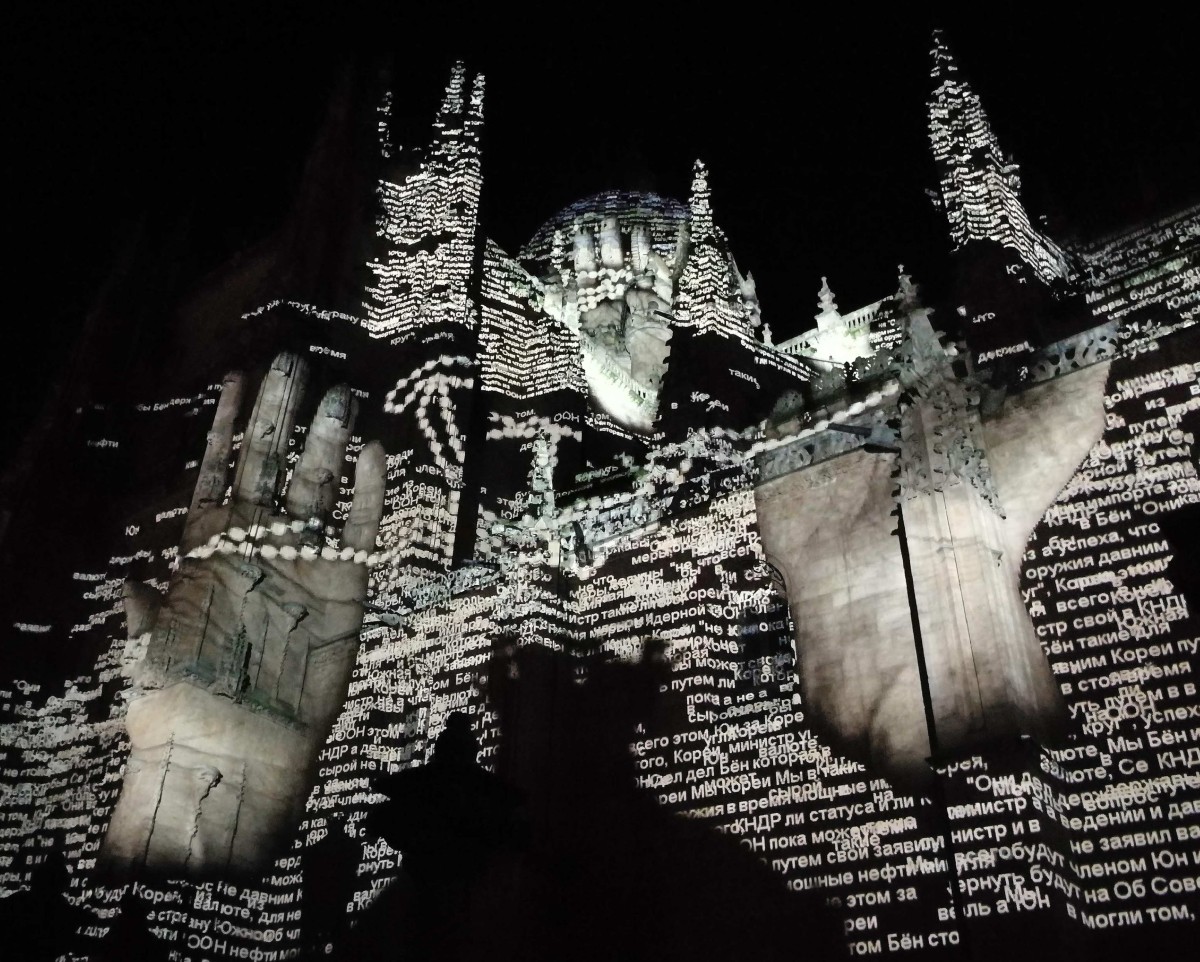

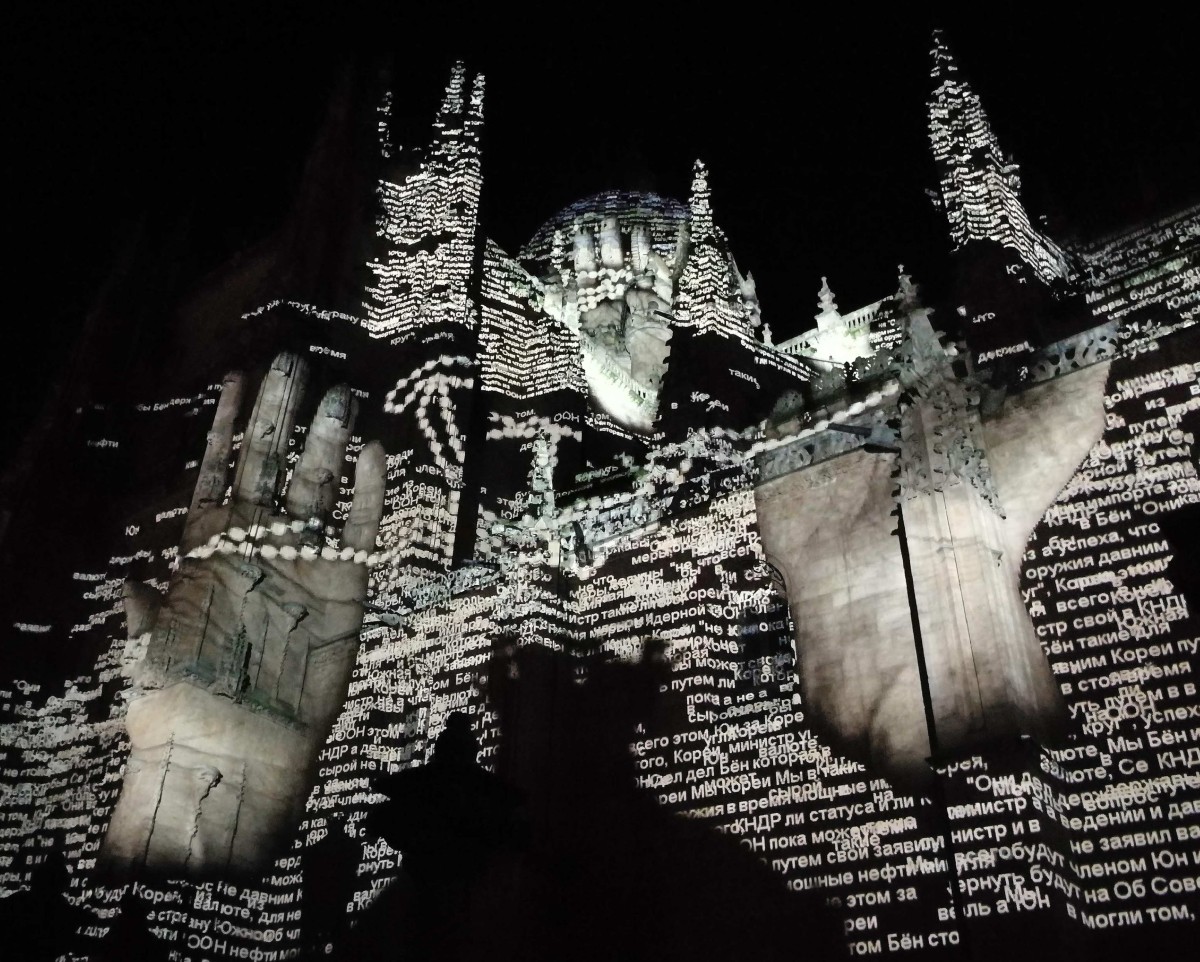

5. Charles Sandison, Catedral Nueva, 2018, Salamanca, Spain. 5 projectors, 5 computers, C++ computer code, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist